The Sacred Visage: An In-Depth Exploration of Native American Ceremonial Masks and Their Collection

Native American ceremonial masks represent one of the most profound and aesthetically compelling forms of indigenous art and spiritual expression. Far more than mere decorative objects, these masks are imbued with deep cultural, historical, and spiritual significance, serving as powerful conduits between the human and spirit worlds. Their collection, both historically and in contemporary contexts, presents a complex narrative intertwined with issues of cultural preservation, appropriation, and repatriation. This article delves into the multifaceted world of Native American ceremonial masks, exploring their diversity, purpose, craftsmanship, symbolism, and the evolving ethics surrounding their acquisition and display.

I. A Tapestry of Diversity: Regional and Tribal Variations

It is crucial to understand that "Native American" encompasses hundreds of distinct nations, each with unique languages, traditions, and artistic expressions. Consequently, ceremonial masks exhibit an astonishing range of styles, materials, and functions across different cultural regions. Generalizing about "Native American masks" risks oversimplification; instead, it is more accurate to appreciate the specific traditions of individual tribes.

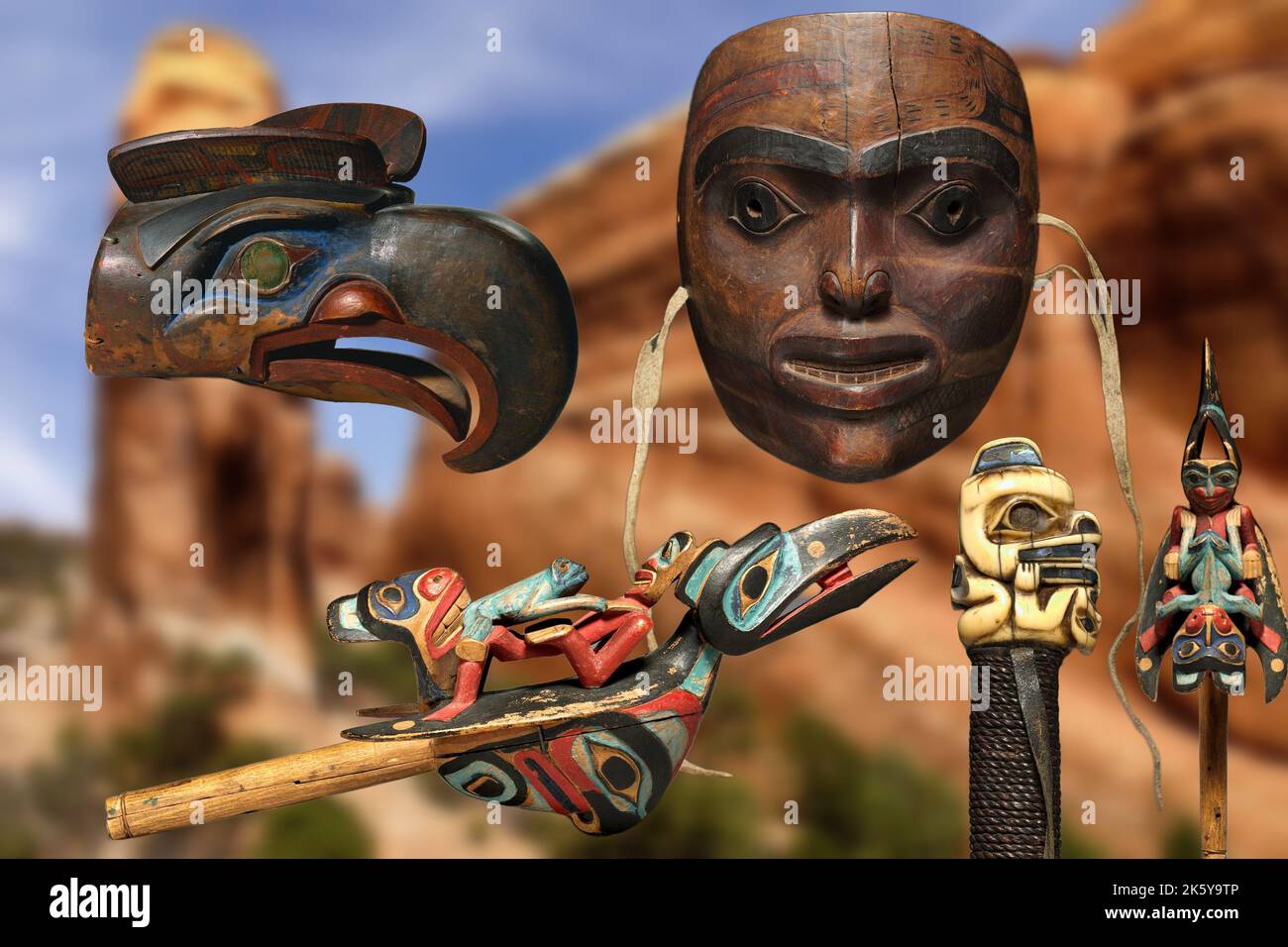

A. Northwest Coast Nations (e.g., Kwakwaka’wakw, Tlingit, Haida):

Perhaps the most visually dramatic and widely recognized are the masks from the Northwest Coast. Carved primarily from cedar, these masks often depict animal spirits (Raven, Bear, Wolf, Eagle), mythological beings, and ancestors. A hallmark of this region is the "transformation mask," an intricately carved piece that can be opened by pulling strings to reveal a different face or character within, symbolizing the shifting nature of identity or the metamorphosis of a spirit. Used extensively in elaborate potlatch ceremonies and winter dance rituals, these masks embody powerful spirits and recount ancestral narratives. Their bold forms, vibrant colors, and meticulous detail are instantly recognizable.

B. Southwest Nations (e.g., Hopi, Zuni):

In the arid Southwest, the Hopi and Zuni peoples are renowned for their Katsina (or Kachina) masks. Katsinam are benevolent spirit beings who bring rain, fertility, and well-being to the community. The masks, often made of cottonwood root, hide, or leather, are painted with geometric designs and symbolic colors, adorned with feathers, corn husks, and other natural materials. Worn by initiated men during ceremonial dances, the masks transform the wearer into the Katsina itself, acting as a living embodiment of the spirit. These ceremonies are central to the agricultural cycle and community life, emphasizing harmony with nature.

C. Northeast Nations (e.g., Iroquois Confederacy):

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) are known for their "False Face" masks, primarily associated with the False Face Society, a healing society. Carved from living trees (basswood or maple) and often depicting distorted, asymmetrical human faces with deeply set eyes, wide mouths, and prominent noses, these masks represent forest spirits. They are believed to possess the power to cure illness, particularly those related to physical ailments and mental distress. Tobacco is often offered to the mask during its creation and use, acknowledging its spiritual potency. These masks are considered living entities and are handled with extreme reverence and specific protocols.

D. Other Regions:

While less common or prominent than in the aforementioned regions, masks also appear in various forms across other Native American cultures. For example, some Inuit and Yup’ik communities in the Arctic create intricate masks, often depicting animal spirits and shamanic visions, used in storytelling and ceremonial dances. In the Plains, while painted faces were more common, some warrior societies or vision quests incorporated specific mask-like elements or headpieces.

II. Purpose and Function: Beyond Aesthetics

The primary function of Native American ceremonial masks transcends mere artistic display. They are integral to spiritual practices, community cohesion, and the transmission of cultural knowledge.

- Spiritual Connection and Transformation: Masks serve as a bridge between the physical world and the spirit realm. By wearing a mask, the individual ceases to be themselves and becomes the spirit, ancestor, or deity represented. This transformation allows the spirit to manifest within the community, offering blessings, healing, or guidance.

- Ritual and Ceremony: Masks are central to a vast array of ceremonies: healing rituals, initiation rites, harvest festivals, seasonal dances, and storytelling performances. Each mask has a specific role, narrative, and accompanying song or dance.

- Healing: As seen with the Iroquois False Face masks, many masks are directly linked to healing practices, believed to draw out illness or restore balance to an individual or community.

- Education and Storytelling: Masks embody myths, histories, and moral lessons. Their use in performances educates younger generations about their heritage, values, and the spiritual cosmology of their people.

- Community Cohesion and Social Control: In some societies, masks are associated with secret societies or specific roles, reinforcing social structure, community values, and collective identity.

III. Craftsmanship, Materials, and Symbolism

The creation of a ceremonial mask is a highly skilled and often sacred process. The choice of materials, the carving techniques, and the symbolic embellishments are all deliberate and imbued with meaning.

- Materials: Common materials include wood (cedar, pine, cottonwood), animal hide, leather, bone, shell, fur, feathers, hair, and plant fibers. Natural pigments derived from minerals, plants, and earth are used for painting. Each material is chosen not only for its aesthetic or practical qualities but also for its inherent spiritual significance. For instance, cedar is highly revered by Northwest Coast peoples, and its spirit is honored in the carving process.

- Craftsmanship: Mask makers are highly respected artisans who often undergo extensive training and spiritual preparation. Carving, painting, and assembling the various components require immense precision and an understanding of the mask’s intended spiritual purpose.

- Symbolism: Every line, color, feature, and adornment on a mask holds symbolic meaning. Colors often represent cardinal directions, elements, or specific powers (e.g., red for life, black for strength, white for purity). Animal features might denote specific characteristics (e.g., eagle for vision, bear for strength). Exaggerated or distorted features can emphasize supernatural qualities or specific character traits.

IV. The Sacred Nature and Protocols

Crucially, ceremonial masks are not merely "art objects" in the Western sense. They are often considered living entities, imbued with spiritual power, and are treated with profound respect and specific protocols. Many masks have restrictions on who can see them, touch them, wear them, or even create them. Some are stored in sacred bundles, fed offerings, or only brought out for specific ceremonies. When removed from their cultural context, these masks can lose their efficacy or, worse, be seen as disrespectful appropriations. This sacred dimension is central to understanding the complexities of their collection.

V. Collection and Repatriation: Ethical Considerations

The history of collecting Native American ceremonial masks is deeply intertwined with colonialism, cultural suppression, and shifting ethical standards.

A. Historical Context of Collection:

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, as Euro-American expansion encroached upon Native lands, many ceremonial masks were acquired by collectors, anthropologists, and museums through various means. Some were purchased, often for nominal sums, from individuals facing economic hardship or under duress due to government policies aimed at suppressing Native cultures (e.g., the ban on potlatches in Canada). Others were simply looted from sacred sites, graves, or homes. The prevailing anthropological view often considered these cultures "dying" and sought to "preserve" their artifacts, without fully appreciating the living, sacred nature of the objects or the rights of their original owners.

B. The Impact on Native Communities:

The removal of masks and other sacred objects from their communities had devastating effects. It disrupted spiritual practices, severed connections to ancestors, hindered cultural transmission, and contributed to a sense of loss and disempowerment. For many tribes, the absence of these objects meant the interruption or cessation of vital ceremonies.

C. The Repatriation Movement and NAGPRA:

In the latter half of the 20th century, a powerful movement for cultural revitalization emerged within Native American communities, coupled with demands for the return of sacred objects. This culminated in landmark legislation like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the United States (1990). NAGPRA mandates that federal agencies and museums receiving federal funds inventory their collections for Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, and repatriate them to culturally affiliated lineal descendants or tribes. Similar efforts and legislation exist in Canada and other countries.

D. Contemporary Ethical Challenges:

Despite NAGPRA, the collection and display of Native American ceremonial masks remain complex.

- Private Collections: NAGPRA applies only to institutions receiving federal funds, leaving a vast number of sacred objects in private hands outside the scope of the law.

- Authenticity vs. Sacredness: Museums and collectors often value masks for their "authenticity" as historical artifacts, while tribes emphasize their living spiritual power and their role in ongoing cultural practices.

- Display Protocols: Even repatriated masks may have specific protocols regarding their handling, storage, and whether they can be publicly displayed at all. Many tribes prefer that sacred masks not be displayed in museums, as this fundamentally misunderstands their purpose.

- Collaboration and Consultation: Modern ethical practice dictates that museums and collectors engage in meaningful consultation with tribal communities regarding the care, display, and potential repatriation of masks. This shift moves from a custodial model to one of partnership and respect.

VI. Revitalization and Contemporary Expressions

Despite the historical challenges, Native American ceremonial mask traditions are not static or relegated to the past. Many communities are actively engaged in revitalizing these practices, with new generations of artists learning traditional carving and painting techniques. Contemporary Native artists also create masks that blend traditional forms with modern interpretations, addressing current social issues while honoring their heritage. This revitalization is a testament to the resilience and enduring spiritual power of these cultures.

VII. Conclusion

Native American ceremonial masks are extraordinary testaments to human creativity, spirituality, and cultural diversity. From the transformative cedar carvings of the Northwest Coast to the rain-bringing Katsina masks of the Southwest and the healing visages of the Iroquois False Face Society, each mask carries a universe of meaning. Their journey from sacred ritual objects to museum collections and, increasingly, back to their communities, reflects a profound shift in understanding and respect. As we move forward, acknowledging the sacred nature of these objects, engaging in ethical collection practices, and prioritizing repatriation and tribal consultation are not merely acts of compliance, but essential steps in fostering genuine cross-cultural understanding and honoring the enduring spiritual legacies of Native American peoples. The masks, in their silent power, continue to speak volumes about identity, belief, and the unbreakable spirit of indigenous cultures.