Replicas of Native American Dwellings and Shelters: An Educational and Scientific Perspective

Abstract: Replicas of Native American dwellings and shelters serve as powerful educational tools, research subjects, and cultural touchstones. This article explores the multifaceted dimensions of their creation, purpose, and impact, drawing upon anthropological, archaeological, and ethnohistorical methodologies. It delves into the diverse forms of Indigenous architecture, the motivations behind replication efforts, the inherent challenges of authenticity and cultural sensitivity, and the best practices for their construction and interpretation. Ultimately, these replicas offer invaluable insights into the ingenuity, adaptability, and rich material culture of Native American peoples across various ecological zones and historical periods.

1. Introduction: The Significance of Indigenous Architecture

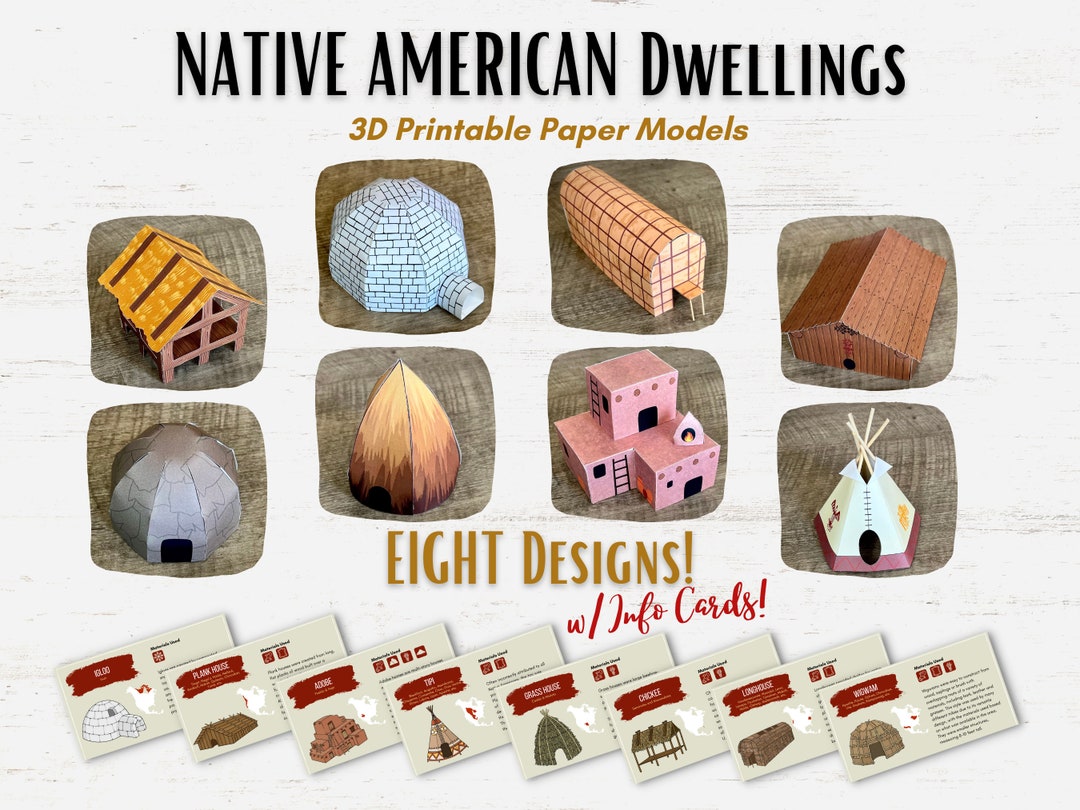

Native American dwellings and shelters represent far more than mere physical structures; they are profound expressions of culture, technology, social organization, and ecological adaptation. From the mobile tipis of the Great Plains to the multi-story pueblos of the Southwest, the longhouses of the Northeast, and the plank houses of the Pacific Northwest, each architectural form embodies centuries of accumulated knowledge about local materials, climate, resource management, and community life.

The creation of replicas of these diverse structures has become a significant endeavor in museums, historical parks, educational institutions, and Indigenous cultural centers. These replicas are not simply curiosities; they are carefully constructed interpretations designed to illuminate the past, engage the present, and inform the future. This article aims to provide an in-depth, encyclopedic examination of the phenomenon of Native American dwelling replicas, exploring their purpose, methodology, challenges, and enduring value.

2. Purposes and Functions of Replicas

The motivations behind constructing Native American dwelling replicas are varied, encompassing educational, research, preservation, and cultural revitalization goals:

2.1. Educational and Interpretive Tools

Perhaps the most common use of replicas is for public education. They offer a tangible, immersive experience that static museum exhibits often cannot provide. Visitors can physically enter these spaces, gain a sense of scale, and imagine daily life within them.

- Museum Exhibits: Full-scale or partial replicas allow museums to showcase specific cultures, technologies, and lifestyles.

- Living History Sites: Locations like Plimoth Patuxet (formerly Plimoth Plantation) or Jamestown Settlement utilize working replicas to demonstrate traditional skills, daily routines, and social interactions, often staffed by interpreters who may be Indigenous descendants.

- School Programs: Replicas provide hands-on learning opportunities, helping students understand concepts of shelter, community, and cultural adaptation in a concrete way.

2.2. Research and Experimental Archaeology

Replicas serve as invaluable tools for archaeological and anthropological research, particularly in the field of experimental archaeology.

- Construction Techniques: Researchers can recreate ancient building methods using period-appropriate tools and materials, gaining insights into labor requirements, skill sets, and the engineering principles employed by past societies. This helps to answer questions about how structures were built and the time and effort involved.

- Material Science: Studying the performance of traditional materials (e.g., thermal properties of adobe, durability of bark, strength of specific timbers) in a reconstructed dwelling provides data on their effectiveness and longevity.

- Space Utilization: Occupying a replica can offer a deeper understanding of how internal spaces were used, how light and ventilation functioned, and the social dynamics influenced by architectural layout.

2.3. Preservation and Documentation of Traditional Knowledge

The construction of replicas, especially when guided by Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers, plays a crucial role in preserving traditional building techniques and oral histories that might otherwise be lost.

- Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer: These projects provide opportunities for elders to teach younger generations about ancestral building methods, material sourcing, and the cultural significance of architectural forms.

- Cultural Revitalization: For many Indigenous communities, rebuilding traditional dwellings is an act of cultural affirmation and revitalization, strengthening identity and connection to heritage.

2.4. Economic Development and Tourism

When managed ethically and in collaboration with Indigenous communities, replicas can contribute to local economies through heritage tourism, providing employment and fostering a deeper appreciation for Indigenous cultures among visitors.

3. Diverse Forms of Native American Dwellings and Their Replication

Native American dwellings are incredibly diverse, reflecting the continent’s vast ecological zones and cultural variations. Replicas strive to represent this diversity:

- Tipis (Plains): Conical structures made of poles and animal hides (or canvas in modern replicas), highly portable and adapted to nomadic hunting. Replication involves understanding pole geometry, hide preparation, and ventilation systems.

- Longhouses (Northeast, Pacific Northwest): Large, rectangular communal dwellings made of timber frames covered with bark or planks. Replicas highlight complex carpentry, community living, and ceremonial spaces.

- Wigwams/Wetus (Northeast): Smaller, dome-shaped or conical shelters made of bent saplings covered with bark, mats, or hides. These demonstrate flexible, adaptable construction for semi-nomadic groups.

- Pueblos (Southwest): Multi-story, multi-room complexes built from adobe (sun-dried mud brick) or stone. Replicas emphasize passive solar design, material sourcing, and communal living structures. Kivas (subterranean ceremonial chambers) are often replicated alongside them.

- Earthlodges (Plains, Midwest): Large, circular structures with a central timber frame covered by earth and sod, providing excellent insulation. Replication involves heavy timber construction and earthwork techniques.

- Hogans (Southwest, Navajo): Distinctive, often hexagonal or circular, log and earth structures, deeply spiritual for the Navajo people. Replication requires specific knowledge of log construction and spiritual protocols.

- Chickees (Southeast, Seminole/Miccosukee): Open-sided, thatched-roof platforms raised on stilts, adapted to hot, humid, and often flooded environments. Replicas showcase elevated living and natural ventilation.

- Plank Houses (Pacific Northwest): Large, rectangular structures made of massive cedar planks, often elaborately carved. Replication demands expertise in woodworking and understanding the social hierarchy reflected in their design.

4. Methodologies and Best Practices in Replica Construction

Creating accurate and meaningful replicas requires a rigorous, interdisciplinary approach:

4.1. Research and Documentation

- Archaeological Data: Excavation reports, structural remains, and artifact analysis provide foundational information on dimensions, materials, and construction techniques.

- Ethnohistorical Records: Accounts from early European explorers, missionaries, and settlers, though often biased, can offer descriptions and illustrations of dwellings.

- Oral Traditions and Indigenous Knowledge: Crucially, collaboration with descendant communities and consulting elders provides invaluable insights into the cultural significance, spiritual protocols, and practical aspects of construction that cannot be gleaned from archaeological or historical texts alone.

- Comparative Ethnography: Studying similar contemporary or historical structures built by related groups can offer additional context.

4.2. Material Sourcing and Preparation

Authenticity often dictates using materials as close as possible to those originally employed. This can involve:

- Local and Natural Materials: Sourcing specific timber, bark, reeds, grasses, stone, or clay from the immediate environment, respecting ecological sustainability.

- Traditional Processing: Replicating methods of curing wood, preparing hides, making adobe bricks, or weaving mats, which can be labor-intensive and require specialized skills.

- Modern Compromises: In some cases, for reasons of durability, safety, or availability, modern equivalents (e.g., canvas instead of hide, treated lumber) may be used, but such compromises should always be clearly communicated and justified.

4.3. Construction Techniques

- Skilled Craftsmanship: Building replicas often requires skilled craftspeople with knowledge of traditional joinery, lashing, weaving, and earth-building techniques.

- Experimental Archaeology: Engaging in the physical act of construction provides empirical data on the time, tools, and human energy required, offering insights into ancient labor organization and technology.

4.4. Community Engagement and Collaboration

This is perhaps the most critical best practice. Replicas of Indigenous structures should ideally be developed with and by descendant communities.

- Shared Ownership: Indigenous communities should have a significant role in design, construction, interpretation, and ongoing management.

- Respect for Intellectual Property: Traditional knowledge, designs, and stories are intellectual property and should be treated with respect, ensuring appropriate permissions and recognition.

- Avoiding Appropriation: Replication efforts must avoid merely "taking" cultural forms without genuine engagement and benefit to the source community.

5. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite their value, the creation and interpretation of replicas present significant challenges:

5.1. Authenticity vs. Practicality

- Material Availability: Many traditional materials are no longer readily available or legally obtainable (e.g., specific old-growth timber, certain animal hides).

- Modern Building Codes and Safety: Replicas for public access must often conform to contemporary safety standards (e.g., fire codes, structural stability), which may necessitate departures from strict historical accuracy.

- Maintenance: Traditional materials often require constant maintenance and are susceptible to environmental degradation, pests, and rot, posing long-term preservation challenges.

5.2. Interpretation and Representation

- Avoiding Stereotypes: Replicas must be interpreted carefully to avoid perpetuating romanticized or inaccurate stereotypes of Native American life as primitive or static. They should emphasize complexity, innovation, and change over time.

- Incomplete Data: Archaeological and ethnohistorical records are often incomplete, leading to educated guesses in reconstruction. These uncertainties should be acknowledged.

- Whose Story? The narrative presented with a replica must reflect the perspectives of the Indigenous people themselves, not solely an external academic or colonial viewpoint.

5.3. Cultural Sensitivity and Protocol

- Sacred Spaces: Some dwelling types or elements within them hold deep spiritual significance. Replicating these requires profound respect and adherence to specific cultural protocols, often meaning certain aspects may not be publicly displayed or even replicated.

- Misrepresentation: Inaccurate or insensitive replicas can be perceived as disrespectful or even offensive by Indigenous communities.

6. Conclusion: Replicas as Bridges to Understanding

Replicas of Native American dwellings and shelters stand as powerful testaments to human ingenuity and cultural resilience. When approached with meticulous research, ethical consideration, and, most importantly, authentic collaboration with Indigenous communities, they transcend mere architectural models. They become living classrooms, experimental laboratories, and vital links to ancestral traditions.

By allowing us to walk through a reconstructed longhouse, feel the insulating earth of an earthlodge, or appreciate the engineering of a tipi, these replicas foster a deeper understanding and empathy for the diverse cultures that have shaped North America. They serve as critical tools for decolonizing narratives, promoting cultural revitalization, and ensuring that the rich architectural heritage of Native American peoples is not only remembered but also vibrantly understood and celebrated for generations to come. The ongoing evolution of best practices, emphasizing Indigenous leadership and a holistic understanding of these structures within their cultural contexts, will ensure their continued relevance and impact.