Unveiling the Ancient Narratives: A Deep Dive into Native American Rock Art and Petroglyph Interpretation

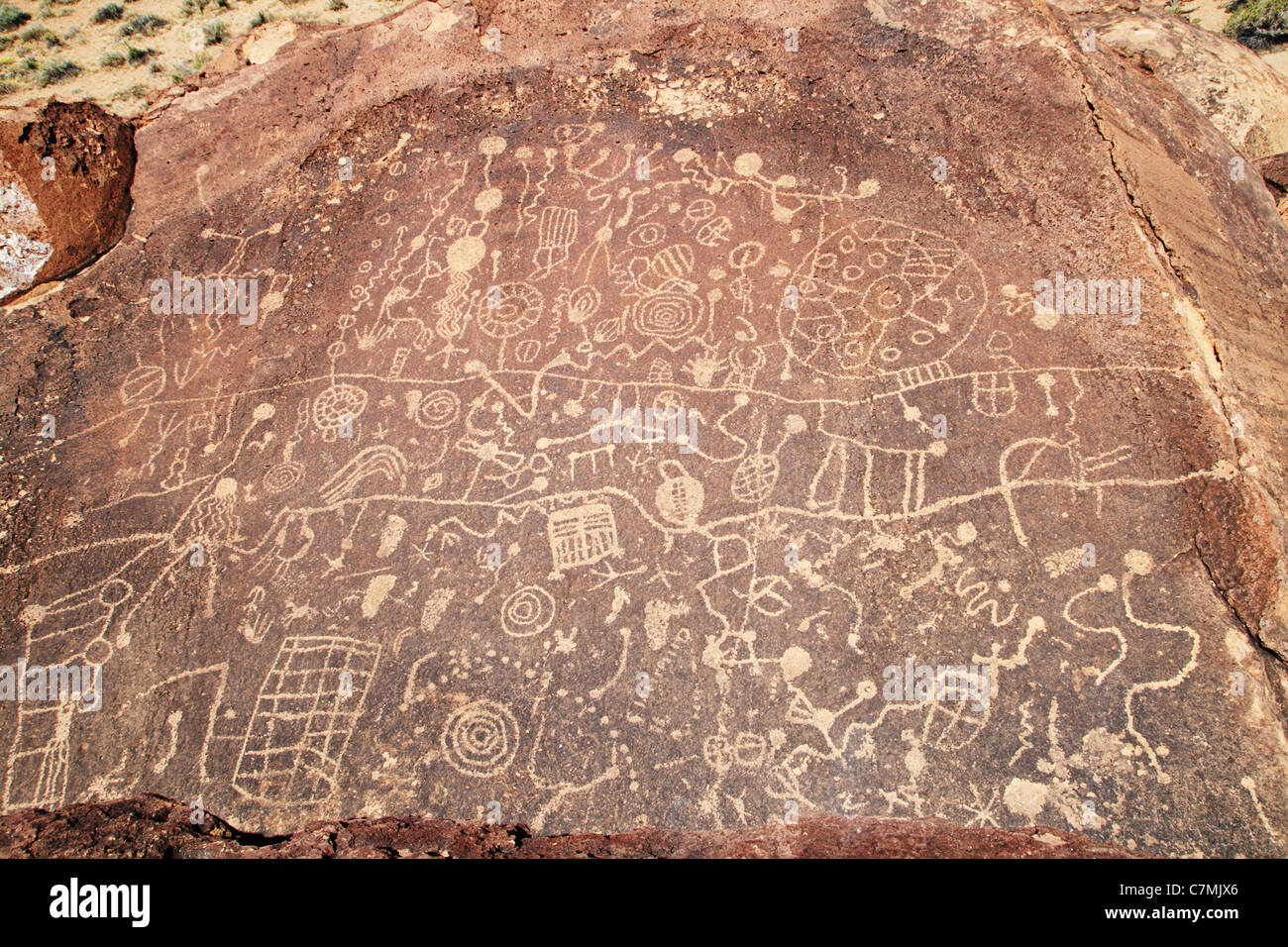

Native American rock art, encompassing both pictographs (painted images) and petroglyphs (carved images), represents one of humanity’s most enduring and enigmatic forms of artistic and spiritual expression. Scattered across the vast landscapes of North and South America, these ancient canvases offer profound insights into the cosmologies, daily lives, historical events, and spiritual practices of countless indigenous cultures spanning millennia. Interpreting these intricate visual narratives is a complex, multidisciplinary endeavor, fraught with challenges but yielding invaluable knowledge about the human past.

Defining the Art Forms: Petroglyphs and Pictographs

The term "rock art" serves as an umbrella for two primary categories:

-

Petroglyphs: These are images created by removing the dark outer layer of rock (patina or desert varnish) to expose lighter rock underneath. Techniques vary widely and include:

- Pecking: Striking the rock surface with a harder stone, often creating a series of dots that form an image. This is the most common method.

- Incising/Scratching: Cutting or scratching lines into the rock with a sharp tool.

- Abrading/Grinding: Rubbing or polishing the rock surface to create grooves or smooth areas.

- Drilling: Less common, but sometimes used to create circular depressions.

The resulting images can range from deeply incised, bold figures to finely scratched, delicate designs, their visibility often dependent on the contrast between the exposed rock and the surrounding patina.

-

Pictographs: These are images painted onto rock surfaces using mineral and organic pigments. The palette available to ancient artists was surprisingly diverse:

- Red and Yellow: Derived from iron oxides like ochre and hematite.

- Black: Sourced from charcoal, manganese dioxide, or burnt organic materials.

- White: Obtained from kaolin clay or gypsum.

- Blue and Green: Less common but sometimes created from copper minerals.

These pigments were often ground into powder, mixed with binders such as animal fat, plant juices, egg whites, or blood, and applied with fingers, brushes made of plant fibers or animal hair, or even blown through hollow tubes. Pictographs are generally more vulnerable to erosion and weathering than petroglyphs, making their preservation and dating more challenging.

Dating the Undatable: Methodologies and Challenges

Determining the age of rock art is crucial for contextualizing its meaning, yet it remains one of the most significant interpretive hurdles.

-

Relative Dating: This approach establishes a chronological sequence without providing absolute calendar dates. Methods include:

- Superposition: When one image is drawn or carved over another, the underlying image is presumed older.

- Patination Analysis: Observing the degree of re-patination (re-darkening) on petroglyphs, as older carvings tend to have a darker, more developed patina. However, patination rates vary significantly with environmental factors.

- Stylistic Analysis: Grouping images based on shared stylistic characteristics and associating them with known archaeological periods or cultural traditions. This method is highly subjective and depends on the establishment of reliable regional chronologies.

-

Absolute Dating: More precise techniques aim to provide specific calendar dates, though these are often challenging to apply directly to rock art:

- AMS Radiocarbon Dating (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry): Applicable to pictographs that contain organic binders (e.g., charcoal, plant fibers, blood). Tiny samples are required, minimizing damage to the art.

- Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL): Can date mineral coatings (e.g., oxalate crusts) that form over or under rock art, thus providing bracketing dates.

- X-ray Fluorescence (XRF): While not directly dating, XRF analysis of pigment composition can identify mineral sources, potentially linking them to dated archaeological contexts.

Directly dating petroglyphs remains particularly difficult, often relying on indirect methods like the dating of associated archaeological deposits or organic materials trapped within the pecked surfaces.

A Kaleidoscope of Meanings: Common Motifs and Iconography

The iconography of Native American rock art is incredibly diverse, reflecting the vast array of cultural traditions across the continent. However, certain broad categories of motifs reappear, offering clues to their potential interpretations:

-

Anthropomorphic Figures: These human-like forms are ubiquitous, ranging from realistic depictions to highly stylized or abstract representations. They may represent:

- Shamans or Spirit Intermediaries: Often adorned with horns, feathers, elaborate headdresses, or holding power objects, suggesting their role in mediating between the human and spirit worlds.

- Ancestors or Deities: Figures of revered beings or mythological heroes.

- Warriors or Leaders: Depicted with weapons or symbols of authority.

- Transformation Figures: Blending human and animal characteristics, indicative of spiritual journeys or shape-shifting.

-

Zoomorphic Figures: Animals are central to Native American cosmologies and subsistence. Common animal motifs include:

- Bighorn Sheep and Deer: Often associated with hunting magic, sustenance, or spiritual power.

- Birds (e.g., Eagles, Owls, Waterfowl): Representing celestial connections, wisdom, messengers, or specific clan affiliations.

- Snakes and Lizards: Symbolizing fertility, healing, water, or powerful underworld spirits.

- Mythological Beasts: Composite creatures that defy natural classification, representing powerful spiritual entities.

-

Geometric and Abstract Designs: These non-representational forms are perhaps the most challenging to interpret but are often deeply symbolic:

- Circles and Spirals: May represent celestial bodies (sun, moon), water, cycles of life, journeys, or altered states of consciousness.

- Zigzags and Wavy Lines: Often associated with water, lightning, snakes, or spiritual pathways.

- Grids, Dots, and Meanders: Could symbolize star charts, maps, communal spaces, or esoteric knowledge.

- Handprints and Footprints: Indicating presence, passage, or spiritual contact.

-

Celestial Symbols: Representations of sun disks, moon crescents, stars, and even specific astronomical events (like supernovae or eclipses) provide evidence of sophisticated astronomical observation and their integration into spiritual beliefs.

Contexts of Creation: Why Was Rock Art Made?

Understanding the why behind rock art is paramount to its interpretation. The motivations were manifold and often intertwined:

-

Ritual and Spiritual Practice: A dominant interpretive framework, particularly the shamanistic model. Many panels are believed to be records of vision quests, trance experiences, or communication with spirit helpers. Sites often possess a palpable "sacredness," chosen for their unique geological features, acoustics, or proximity to power spots. Rites of passage, healing ceremonies, and prayers for rain or successful hunts were also likely occasions for rock art creation.

-

Narrative and Historical Record: Rock art could serve as a visual archive of significant events. Panels might depict:

- Battles or Raids: Recording conflicts between groups.

- Migrations or Journeys: Charting routes or significant stopping points.

- Important Encounters: Documenting interactions with other cultures or, later, with Europeans (e.g., horses, guns, missionaries).

- Calendrical or Astronomical Observations: Marking solstices, equinoxes, or rare celestial phenomena, crucial for agricultural or ceremonial cycles.

-

Territorial and Social Markers: Rock art could delineate group territories, mark important trails, warn outsiders, or identify clan affiliation. Certain motifs might have served as visual "signatures" or emblems of particular kin groups.

-

Instructional and Pedagogical Purposes: Some panels may have functioned as teaching aids, illustrating myths, moral lessons, hunting techniques, or the spiritual landscape for younger generations. These sites could have been outdoor classrooms where cultural knowledge was transmitted.

-

Cosmological Worldviews: Fundamentally, rock art reflects complex indigenous understandings of the universe – the interconnectedness of all living things, the relationship between humans and the natural world, and the various spiritual realms inhabited by ancestors, deities, and spirit beings.

The Interpretive Maze: Challenges and Methodologies

Interpreting Native American rock art is a delicate balance of scientific inquiry, cultural sensitivity, and speculative inference. Several significant challenges persist:

- Cultural Discontinuity: The greatest hurdle is the loss of direct cultural knowledge. Many of the societies that created this art no longer exist in their original forms, or their languages and oral traditions, which once provided the keys to interpretation, have been lost or significantly altered.

- Ethnocentric Bias: Interpreters, often from Western academic traditions, risk imposing their own cultural frameworks, logical systems, and artistic conventions onto indigenous belief systems, leading to misinterpretations.

- Multivocality and Esotericism: Rock art often possesses multiple layers of meaning, understood differently by various members of a society (e.g., commoners vs. shamans). Some knowledge was inherently esoteric, meant only for initiates or specific individuals, and never intended for broad external interpretation.

- Secrecy and Sacredness: Many indigenous communities consider rock art sites and their associated meanings to be sacred and private, not for public or academic dissection. Respecting these boundaries is paramount.

- Superimposition and Palimpsests: Many panels contain images created over vast periods, often overlapping. Differentiating these layers and understanding their individual or combined meanings is complex.

To navigate this interpretive maze, scholars employ a range of methodologies:

- Ethnographic Analogy: This involves drawing comparisons between the rock art and documented ethnographic accounts, oral traditions, myths, and spiritual practices of descendant communities or culturally related groups. This approach requires extreme caution, as meanings can shift significantly over time and across cultures.

- Archaeological Context: Analyzing the rock art within its broader archaeological setting – the associated habitation sites, tools, ceremonial structures, and other artifacts – can provide crucial contextual clues about the culture that produced it.

- Landscape Archaeology: Studying the relationship between the rock art, the specific rock feature, and the surrounding natural and cultural landscape. The choice of location was often highly intentional and spiritually significant.

- Indigenous Collaboration: Increasingly, and most ethically, interpretation is conducted in partnership with contemporary Native American communities. Their direct ancestral knowledge, oral histories, and spiritual insights are invaluable and often provide the most authentic interpretations, while also ensuring cultural protocols and sensitivities are respected.

- Scientific Analysis: Advanced imaging techniques (e.g., D-Stretch, photogrammetry) can enhance faint details. Pigment analysis and dating techniques provide chronological anchors.

Conclusion

Native American rock art stands as an enduring testament to the rich intellectual, spiritual, and artistic lives of indigenous peoples. It is a vast, open-air library, each panel a page inscribed with stories, prayers, histories, and cosmological insights. While the challenges of interpretation are significant, ongoing interdisciplinary research, coupled with a deep commitment to ethical engagement and collaboration with Native American communities, continues to unlock these ancient narratives. These powerful images not only connect us to the profound past but also remind us of the enduring human capacity for creativity, spiritual connection to the land, and the universal impulse to leave a lasting mark on the world.