Celestial Tapestries: Displays of Native American Astronomy and Calendars

The cosmos, a boundless canvas of stars, planets, and cyclical phenomena, served as an ancient and profound source of knowledge for Native American cultures across the vast expanse of North and South America. Far from being mere observers, indigenous peoples developed sophisticated systems of astronomy and calendrics, meticulously interwoven with their spiritual beliefs, agricultural practices, social structures, and ceremonial cycles. These intricate understandings were not confined to abstract thought but were demonstrably "displayed" through a diverse array of physical manifestations, ranging from monumental architecture and intricate rock art to portable devices and the very fabric of their oral traditions and ceremonial life. This article delves into these multifaceted displays, exploring their forms, functions, and enduring significance as testaments to a deep human-cosmic connection.

The Foundations of Indigenous Celestial Knowledge

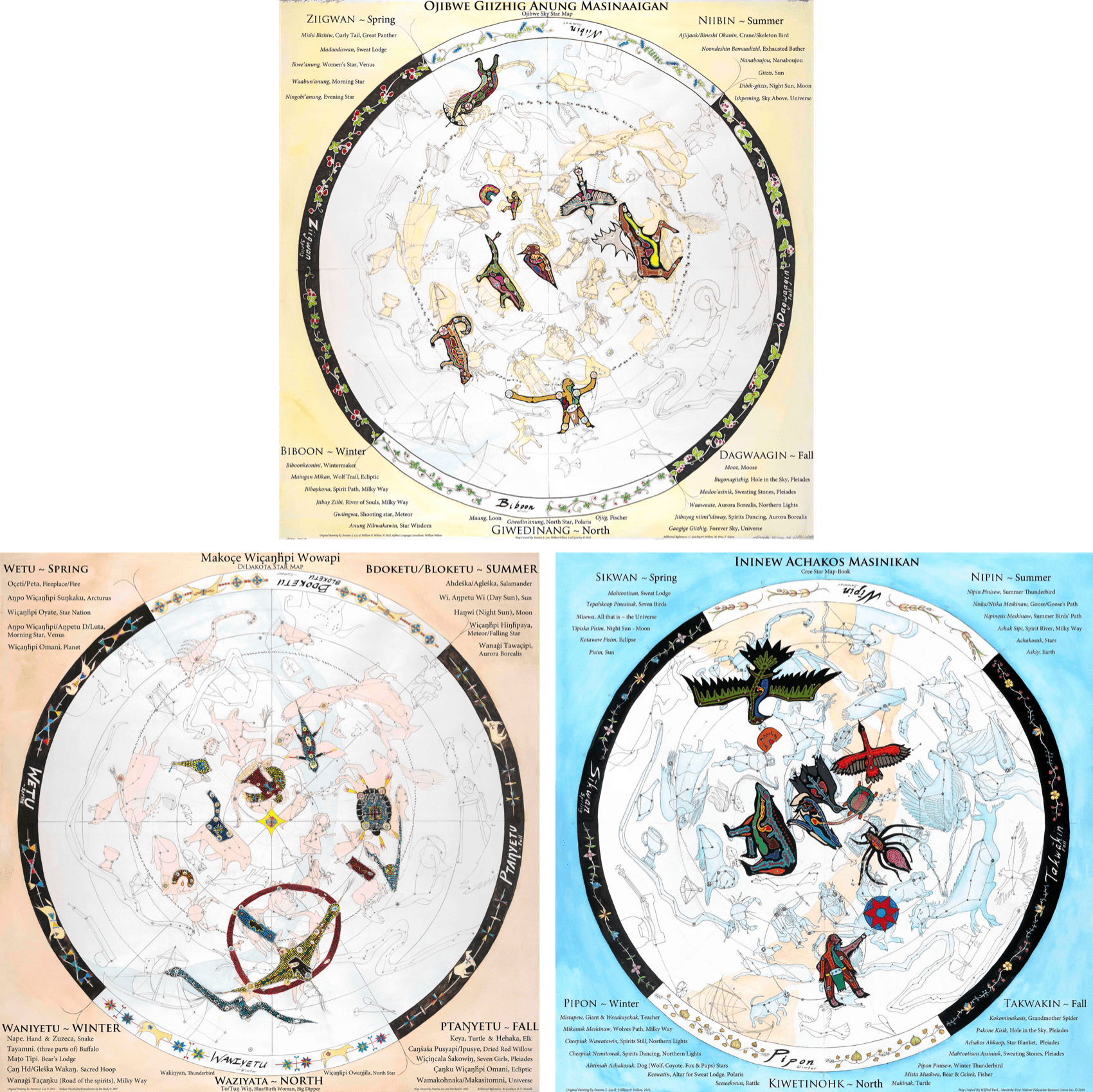

Before examining the displays themselves, it is crucial to understand the foundational principles of Native American celestial observation. Unlike Western astronomy, which often emphasizes detached scientific inquiry, indigenous astronomy was deeply holistic and practical. The sky was not merely an object of study but a living, interactive entity, a sacred realm mirroring earthly existence. Observations of the sun, moon, prominent stars, constellations, and planetary movements (especially Venus) were undertaken with precision, often over generations, and passed down through oral histories, ritual, and visual markers.

The primary purposes of these observations were manifold:

- Timekeeping: Tracking the passage of days, lunar months, and solar years.

- Calendrics: Establishing agricultural cycles (planting, harvesting), hunting seasons, and the timing of ceremonial events.

- Navigation: Guiding migrations and journeys across vast landscapes.

- Cosmology: Understanding the structure of the universe, humanity’s place within it, and the will of the divine.

- Pedagogy: Teaching younger generations about their heritage, responsibilities, and the natural world.

These profound insights were then translated into tangible "displays" that served as communal almanacs, sacred texts, and instructional tools.

Monumental Architecture as Celestial Observatories and Calendars

Perhaps the most impressive and enduring displays of Native American astronomy are embedded within their monumental architecture. These structures were not just dwellings or ceremonial spaces but carefully designed observatories, aligning with key celestial events.

1. Chaco Canyon (Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans)

The Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, flourishing between 850 and 1250 CE, left behind some of the most sophisticated archaeoastronomical sites.

- Fajada Butte and the "Sun Dagger": This iconic site on Fajada Butte consists of three large stone slabs leaning against the cliff face. At summer solstice noon, a "dagger" of light, passing through a gap in the slabs, precisely bisects a spiral petroglyph carved into the rock. At winter solstice, two daggers frame a smaller spiral, and at the equinoxes, a single dagger bisects another spiral. This remarkable display served as an accurate solar calendar, marking the most critical points of the agricultural year.

- Kivas and Great Houses: The large, circular subterranean ceremonial structures known as kivas, and the monumental multi-story "great houses" like Pueblo Bonito and Casa Rinconada, exhibit numerous astronomical alignments. Doorways, windows, and entire building axes were oriented to capture the rising or setting sun at solstices and equinoxes, or the extreme positions of the moon (lunar standstills). Casa Rinconada, a massive great kiva, is particularly noted for its precise alignments that mark cardinal directions and solar events, suggesting its use as a communal calendric and ceremonial center. These alignments served not only as practical timekeepers but also as sacred geometry, integrating the human-made world with the cosmic order.

2. Medicine Wheels (Plains Tribes)

Found across the North American plains, Medicine Wheels are large, circular stone constructions characterized by a central cairn, an outer ring of stones, and spokes radiating from the center. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, dating back over 7,000 years, is a prime example.

- Solar Alignments: The Bighorn Wheel clearly marks the summer solstice sunrise and sunset, with specific cairns aligning precisely with these events.

- Stellar Alignments: Researchers have also identified alignments with the heliacal (first visible) rising of prominent stars such as Aldebaran, Rigel, and Sirius, which would have signaled specific times of year or guided the movements of nomadic groups.

- Calendric and Ceremonial Function: While their exact purpose remains debated, Medicine Wheels functioned as both astronomical observatories and calendric devices, guiding seasonal movements, hunting cycles (especially buffalo), and sacred ceremonies like the Sun Dance. They are physical displays of a deep understanding of celestial mechanics, etched into the landscape.

Rock Art: Petroglyphs and Pictographs as Calendric Records

Across the Americas, rock art — petroglyphs (carved into rock) and pictographs (painted on rock) — serves as another crucial category of astronomical and calendric displays. These visual narratives recorded celestial events, marked specific times, and communicated cosmological knowledge.

- Solar and Lunar Markers: Common motifs include sun symbols (circles with rays), moon crescents, and stylized representations of stars. Many sites feature specific petroglyphs that are illuminated or cast shadows in particular ways only during solstices or equinoxes, functioning as fixed calendric markers.

- Supernova Depictions: One of the most famous examples is found at Chaco Canyon and other Ancestral Puebloan sites, believed to depict the supernova of 1054 CE, which created the Crab Nebula. These images, often alongside a crescent moon and a single bright star, demonstrate a keen awareness of transient celestial phenomena and their recording.

- Constellation Maps: Some rock art may represent specific constellations or star patterns, serving as visual aids for navigating the night sky or as references for oral traditions and mythologies. For example, the "Big Dipper" or "Pleiades" (known to many tribes as "the Dancers" or "the Seven Sisters") often feature in calendric stories related to seasonal changes.

- Seasonal Cycles: Petroglyphs often depict animals or human activities associated with specific seasons, subtly linking the celestial calendar to earthly events like migrations, harvests, or ceremonies. These displays are not merely decorative but are integral to preserving and transmitting knowledge across generations.

Portable and Material Displays

Beyond monumental architecture and fixed rock art, Native American cultures also created portable objects that functioned as calendric and astronomical displays, often used for personal or community-level timekeeping.

1. Calendric Sticks and Tablets

- Notched Sticks: Many tribes, including the Zuni, Hopi, and others, utilized notched sticks or wooden tablets to keep track of lunar months, ceremonial cycles, and the passage of days. Each notch could represent a day, a moon phase, or a significant event. These simple yet effective tools served as tangible, tactile calendars, often accompanied by oral narratives that provided context for each marked period. The number of notches, their spacing, and any accompanying symbols would convey specific calendric information.

- Winter Counts (Plains Tribes): While not strictly astronomical, Winter Counts (often painted on hides or cloth) are pictographic calendars that recorded the most significant event of each year (winter-to-winter) for a particular band or tribe. Each image served as a mnemonic device, triggering detailed oral histories of the past. While focused on historical events, the very act of annual recording connects to a deep calendric awareness.

2. Wampum Belts (Northeastern Woodlands)

Wampum belts, crafted from shell beads, primarily served as records of treaties, laws, and historical events for tribes like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Algonquin. While not direct astronomical calendars, their intricate patterns could sometimes incorporate symbols or sequences that marked specific celestial events or cycles relevant to the recorded agreement. The passage of time was inherently understood and marked in the sequence of events recorded on the belts, embodying a form of historical calendric display.

3. Pottery and Textiles

While less direct in their calendric function, designs on pottery, baskets, and textiles frequently incorporate cosmological symbols: sun, moon, stars, and directional motifs. These artistic expressions display the cultural understanding of the cosmos, reflecting the patterns and forces observed in the sky. A potter’s depiction of the sun, for example, might not be a direct calendric marker, but it displays the centrality of the sun to their worldview, which in turn informs their calendric system.

The Interwoven Nature: Cosmology, Culture, and Calendar

What makes Native American astronomical and calendric displays particularly profound is their complete integration into the fabric of daily life and spiritual belief. These were not isolated scientific endeavors but living traditions that animated ceremonies, guided resource management, and reinforced communal identity.

- Ceremonial Cycles: The Sun Dance of the Plains, the Green Corn Ceremony of the Southeast, and the Soyal Ceremony of the Hopi are examples of rituals precisely timed by astronomical observations. The architectural alignments and rock art served as prompts and stages for these critical annual events, linking the human experience directly to the cosmic rhythm.

- Oral Traditions: Crucially, the physical displays were often mnemonic devices for rich oral traditions. The meaning of a particular alignment, a petroglyph, or a notch on a stick was elucidated through stories, songs, and teachings passed down through generations. These oral histories provided the narrative context and spiritual significance that transformed a mere observation into a profound cultural display.

- Diversity and Regional Variation: It is vital to remember that "Native American" encompasses hundreds of distinct cultures. While general patterns exist, the specific forms and interpretations of astronomical and calendric displays varied widely depending on environment, belief systems, and cultural practices. From the elaborate observatories of the Puebloans to the celestial navigation of Polynesian voyagers (some of whom settled in the Americas), the ingenuity and adaptability were immense.

Conclusion

The displays of Native American astronomy and calendars represent a breathtaking testament to human ingenuity, spiritual depth, and an intimate connection with the natural world. From the monumental precision of the Sun Dagger at Chaco Canyon and the sacred geometry of the Medicine Wheels, to the vivid narratives of rock art and the practical utility of notched sticks, these diverse forms collectively articulate a sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics and temporal cycles. Far from being mere curiosities, these displays were vital tools for survival, spiritual expression, and cultural cohesion, deeply integrating the cosmic order into every aspect of indigenous life. They stand today as enduring reminders of a worldview that saw the heavens not as distant and abstract, but as a dynamic and sacred tapestry intimately woven with the destiny of humanity.