The Enduring Tapestry: A Deep Dive into Native American Linguistic Diversity

The linguistic landscape of the Americas, prior to European contact, was a kaleidoscope of unparalleled diversity, representing a significant portion of the world’s language families and isolates. Far from being a monolithic entity, "Native American languages" encompass an astonishing array of distinct systems of communication, each a unique window into a culture’s worldview, history, and knowledge. This profound linguistic heritage, while severely impacted by centuries of colonization and assimilation, continues to be a vibrant field of study, revealing the immense ingenuity and adaptability of human language.

The Scale of Pre-Contact Diversity

Estimates suggest that before 1492, there were between 1,000 and 2,000 distinct Indigenous languages spoken across the Americas, from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego. North America alone hosted approximately 300 languages, grouped into around 60 major language families—a number far exceeding the linguistic diversity of entire continents like Europe or Australia. In Mesoamerica, a region of intense cultural development, and South America, particularly the Amazon basin, the linguistic fragmentation was even greater, with numerous small, highly distinct language groups.

This extraordinary diversity is a testament to thousands of years of human migration, isolation, and independent linguistic evolution. Unlike the relatively recent spread of Indo-European languages across Eurasia, the Americas saw populations settle and diversify over tens of millennia, leading to a deep linguistic time depth and the development of unique sound systems, grammars, and vocabularies.

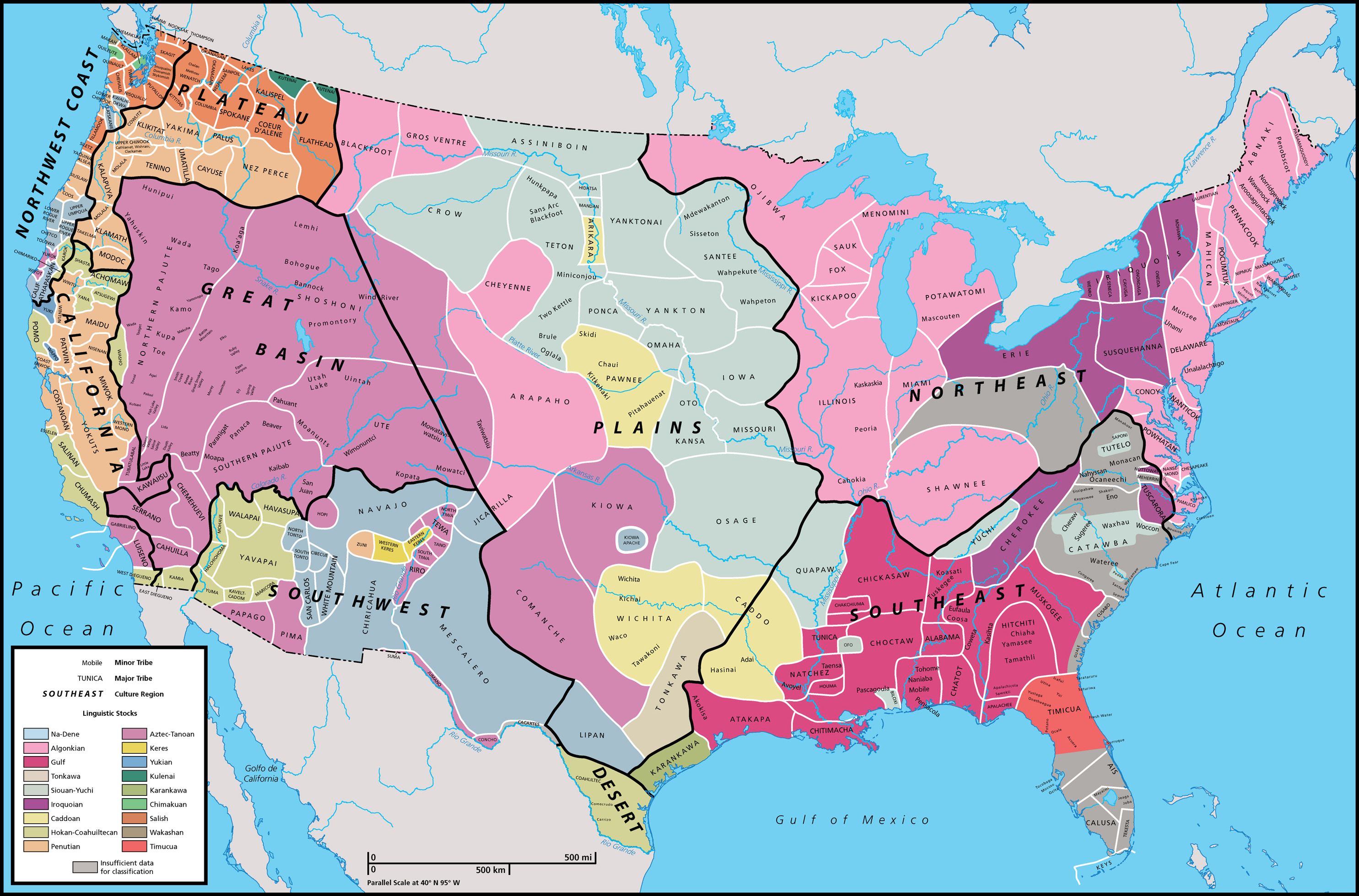

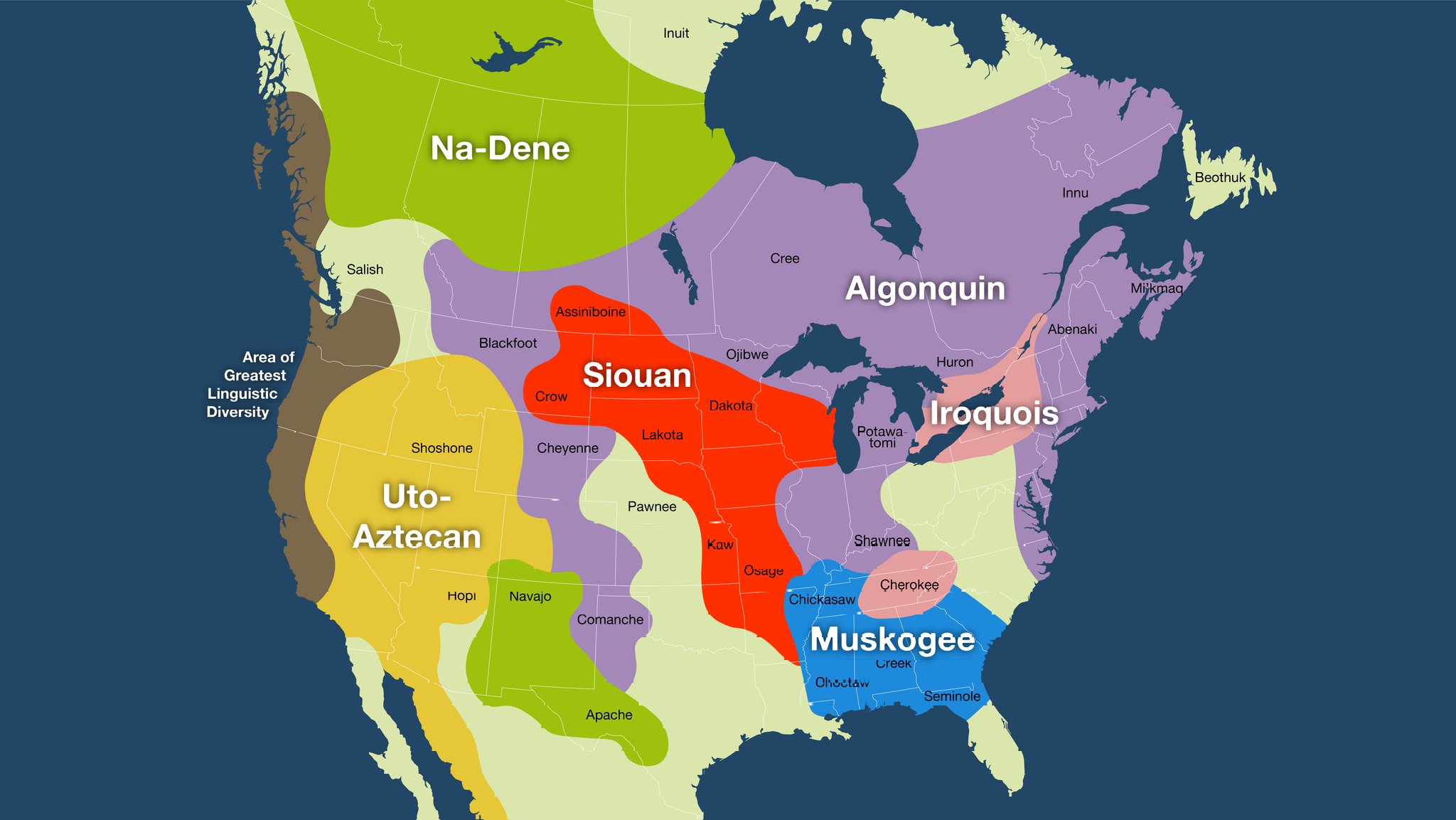

Major Language Families and Their Geographical Reach

Classifying Native American languages is a complex task, often complicated by limited historical data, language loss, and ongoing debates among historical linguists. However, several large and well-established language families stand out:

In North America:

- Na-Dené (Athabaskan-Eyak-Tlingit): One of the largest families, stretching across vast areas. Its most prominent branch, Athabaskan, includes languages like Navajo (Diné Bizaad), Apache, and many languages spoken in interior Alaska and western Canada (e.g., Dene, Gwich’in). Tlingit and Eyak (now extinct) are also part of this family, spoken along the Pacific Northwest coast.

- Algonquian: Found primarily in the eastern woodlands, Great Lakes, and Canadian plains. Key languages include Cree, Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin), Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Fox, and historically, Narragansett and Lenape. These languages share a common ancestor and exhibit distinctive polysynthetic features.

- Siouan-Catawban: Spanning the Great Plains and southeastern United States. The Siouan branch includes Lakota, Dakota, Omaha-Ponca, and Crow. The Catawban branch, once spoken in the Carolinas, is now largely moribund.

- Uto-Aztecan: A vast family extending from the Great Basin of the U.S. southwest down into Mesoamerica. It encompasses languages like Hopi, Shoshone, Ute, Comanche, and the historically significant Nahuatl (the language of the Aztec empire).

- Iroquoian: Centered around the Great Lakes and eastern woodlands. Famous for languages such as Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca (the "Five Nations" of the Iroquois Confederacy), and Cherokee, historically spoken in the southeastern U.S.

- Muskogean: Predominantly in the southeastern United States, including Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole.

- Salishan: Found in the Pacific Northwest, characterized by complex phonology and morphology, including languages like Squamish, Shuswap, and Lushootseed.

In Mesoamerica:

- Mayan: Spoken across southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. This family boasts a long written tradition and includes languages like K’iche’, Kaqchikel, Yucatec Maya, and Tzotzil.

- Oto-Manguean: A large and diverse family in central and southern Mexico, including Mixtec, Zapotec, Otomi, and Mazatec.

- Mixe-Zoquean: Also in southern Mexico, known for languages like Mixe and Zoque.

In South America:

- Quechuan: The largest Indigenous language family in the Americas by number of speakers, primarily in the Andean regions of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Colombia. It was the language of the Inca Empire.

- Aymaran: Also in the Andes, closely related to Quechuan, with Aymara being a major language in Bolivia and Peru.

- Tupi-Guarani: A widespread family in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina, with Guarani being an official language of Paraguay and spoken by millions.

Linguistic Isolates and Unclassified Languages

Beyond these large families, many Native American languages are classified as linguistic isolates, meaning they have no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language. These are like single, solitary branches on the linguistic tree, representing ancient lineages that diversified and lost their relatives over millennia, or whose relatives simply haven’t been identified. Examples include Kutenai (Montana/Idaho), Zuni (New Mexico), and Purépecha (Mexico). The very existence of isolates underscores the deep time depth and independent development of language in the Americas.

Furthermore, a number of languages remain unclassified due to insufficient documentation, often because they went extinct before comprehensive linguistic study could be conducted. This highlights the urgent need for ongoing research and revitalization efforts.

Typological Features and Unique Characteristics

Native American languages exhibit a fascinating array of structural features that challenge common assumptions about how languages work, often diverging significantly from Indo-European norms.

- Polysynthesis: Many Native American languages are highly polysynthetic, meaning that words (especially verbs) can be incredibly long and complex, incorporating multiple morphemes (meaningful units) that would be separate words in English. A single verb might express the subject, object, tense, aspect, mood, location, and even the instrument used, making a sentence like "I picked up the small round object from the water" potentially a single word. This is prominent in Algonquian, Iroquoian, and some Athabaskan languages.

- Agglutination: Related to polysynthesis, agglutination involves adding multiple suffixes or prefixes to a root word, each with a distinct grammatical function. Quechua and Nahuatl are classic examples.

- Evidentiality: A striking feature in many languages (e.g., in the Siouan and some Athabaskan families) is evidentiality, where speakers must explicitly mark the source of their information (e.g., whether they saw it, heard it, inferred it, or were told it). This is a mandatory grammatical category, unlike in English where it’s optional ("I saw that he left" vs. "He left, apparently").

- Noun Incorporation: In some languages, a noun can be incorporated directly into the verb, forming a single complex word. For instance, in Mohawk, instead of saying "I wash the baby," one might say "I baby-wash."

- Ergativity: While many languages are nominative-accusative (like English, where subjects of transitive and intransitive verbs are treated similarly), some Native American languages (e.g., in Mayan and some Salishan languages) are ergative-absolutive. This means the subject of an intransitive verb is treated the same way as the object of a transitive verb, while the subject of a transitive verb is marked differently.

- Unique Phonologies: Many languages feature sounds not found in English, such as ejectives (consonants produced with a burst of air from a closed glottis), glottal stops, and complex systems of vowel harmony or tone.

- Semantic Categories: Languages often categorize the world in unique ways, with different distinctions in kinship terms, color terms, or ways of counting. For example, some languages might have different words for "to kill an animal" versus "to kill a human."

Historical Context, Decline, and Endangerment

The arrival of Europeans initiated a catastrophic period for Native American languages. Disease, warfare, forced relocation, and especially policies of assimilation (such as the residential/boarding school system in the U.S. and Canada) actively suppressed Indigenous languages, often punishing children for speaking their native tongues. This led to a dramatic intergenerational language shift towards English, Spanish, Portuguese, or French.

Today, the vast majority of Native American languages are critically endangered. Of the original hundreds, only a handful (like Navajo, Cree, and Quechua) have robust numbers of speakers, while many are spoken only by elders, with no intergenerational transmission to younger generations. Many have already fallen silent. This loss is not merely linguistic; it represents the irreparable loss of unique knowledge systems, cultural identities, oral literatures, and distinct ways of understanding the world.

Revitalization Efforts and the Future

Despite the historical trauma, there is a powerful and growing movement for language revitalization across the Americas. Communities, often supported by linguists and anthropologists, are working tirelessly to document, teach, and breathe new life into their ancestral languages.

Key revitalization strategies include:

- Language Immersion Schools: Creating environments where children learn entirely in the Indigenous language.

- Master-Apprentice Programs: Pairing fluent elders with dedicated learners for intensive one-on-one instruction.

- Curriculum Development: Creating teaching materials, dictionaries, and grammars.

- Digital Resources: Utilizing apps, online dictionaries, and social media to make languages accessible.

- Community Language Programs: Classes, camps, and cultural events centered around language use.

- Governmental Support: Legislation like the Native American Languages Act of 1990 in the U.S. has provided some recognition and funding for language preservation.

While the challenges are immense—limited resources, aging speaker populations, and the dominance of majority languages—the passion and dedication of Indigenous communities offer hope. Successful revitalization efforts are seen in languages like Wampanoag, which has been brought back from dormancy, and Hawaiian, which has seen a significant increase in speakers due to immersion schools.

Conclusion

The linguistic diversity of Native American languages is a profound testament to human cognitive capacity and cultural ingenuity. Each language is a complex, intricate system, a repository of unique knowledge, history, and a distinct philosophy. The ongoing struggle to preserve and revitalize these languages is not just about linguistics; it’s about cultural survival, self-determination, and safeguarding an invaluable part of humanity’s shared heritage. Understanding and appreciating this diversity enriches our understanding of what language is and what it means to be human.