The Shadow of Assimilation: A Deep Dive into Native American Boarding School History and Impact

The history of Native American boarding schools represents a dark and often overlooked chapter in the annals of United States history, a systematic attempt by the federal government and various religious organizations to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-American culture. These institutions, operating predominantly from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, were founded on the explicit premise that Indigenous cultures were inferior and that Native peoples needed to be "civilized" to integrate into mainstream American society. The legacy of these schools is one of profound trauma, cultural devastation, and intergenerational suffering that continues to impact Indigenous communities today.

I. Historical Context and Ideological Foundations

The establishment of Native American boarding schools was not an isolated phenomenon but rather a direct extension of broader U.S. federal Indian policy during the post-Civil War era. As westward expansion intensified and Native lands were increasingly encroached upon, the U.S. government sought new strategies to manage what it termed the "Indian Problem." Earlier policies of removal and concentration on reservations had proven costly and often violent. A new approach emerged, championed by reformers and military figures, which posited that the most effective way to address the "problem" was to eradicate Indigenous cultures and identities through education.

A pivotal figure in this movement was Richard Henry Pratt, an army officer and founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, established in 1879. Pratt’s infamous motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," encapsulated the philosophy behind these institutions. He believed that by removing Native children from their families, languages, and cultural practices, they could be "civilized" and trained for roles in white society, thereby dissolving tribal identities and ultimately facilitating the appropriation of Native lands. This ideology was rooted in a blend of Manifest Destiny, Social Darwinism, and religious fervor, all contributing to the belief in the inherent superiority of white, Christian culture.

Federal funding for these schools began in earnest in the 1870s, augmenting existing efforts by various Christian denominations (Catholic, Protestant, Quaker) that had already established mission schools on or near reservations. By the early 20th century, hundreds of such schools, both off-reservation (like Carlisle) and on-reservation, were in operation, enrolling tens of thousands of Native children annually.

II. The Boarding School Experience: A System of Cultural Eradication

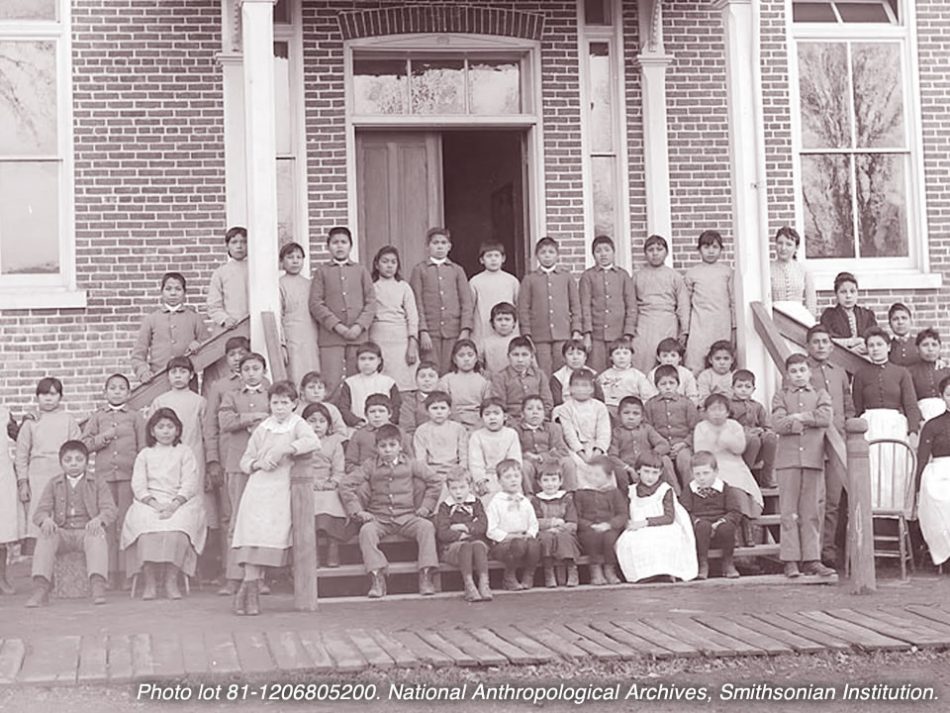

The experience of children within these boarding schools was characterized by strict discipline, cultural suppression, and often severe abuse. Upon arrival, children were immediately stripped of their Indigenous identities. Their traditional clothing was confiscated, their hair was cut short (a practice often symbolizing mourning or shame in many Native cultures), and their names were replaced with English ones. Speaking their native languages was strictly forbidden, often enforced through harsh corporal punishment, including beatings, solitary confinement, and withholding of food.

The curriculum was designed not for academic excellence but for vocational training. Boys were taught trades such as carpentry, farming, and blacksmithing, while girls were trained in domestic skills like sewing, cooking, and cleaning, preparing them for subservient roles in white society or to maintain assimilated homes. Academic subjects were often rudimentary and given less emphasis than manual labor. Children were expected to perform extensive chores and work, effectively subsidizing the schools’ operations through their labor, often under harsh and exploitative conditions.

Beyond the structured curriculum, daily life was rigorously regimented, often mimicking military discipline. Children marched to classes, meals, and chores, and their lives were devoid of the warmth, community, and cultural richness of their home environments. Family visits were rare, and correspondence was often censored or forbidden, severing critical emotional and cultural ties.

The living conditions in many schools were abysmal. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate nutrition, and lack of proper medical care were rampant. These conditions made children highly susceptible to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, influenza, and trachoma. Mortality rates were significantly higher than for the general population, and many children died at the schools, often buried in unmarked graves, their deaths rarely communicated to their families.

Perhaps the most devastating aspect of the boarding school experience was the widespread abuse. Physical, emotional, psychological, and sexual abuse by school staff (teachers, administrators, and religious figures) was endemic. Children were subjected to brutal beatings, humiliation, emotional neglect, and sexual exploitation. These traumatic experiences left deep and lasting scars, profoundly affecting survivors for the rest of their lives.

III. The Profound and Enduring Impact

The impacts of the Native American boarding school system were multifaceted and profoundly destructive, affecting individuals, families, and entire tribal nations for generations.

A. Individual and Psychological Trauma:

Survivors of boarding schools often experienced deep psychological trauma, leading to high rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. The loss of identity, the forced separation from family, and the experience of abuse fostered feelings of shame, anger, and worthlessness. Many struggled with their sense of self, caught between the two cultures but fully belonging to neither. The inability to grieve for lost childhoods and cultural heritage contributed to complex and unresolved trauma.

B. Intergenerational Trauma:

The trauma experienced by boarding school survivors did not end with them; it was passed down through generations. Parents who were denied healthy models of parenting often struggled to raise their own children, leading to cycles of neglect, abuse, or emotional distance within families. The breakdown of traditional family structures and kinship networks, the erosion of language, and the loss of cultural teachings meant that children of survivors were often disconnected from their heritage and lacked the foundational cultural knowledge that provides identity and resilience. This intergenerational trauma manifests in higher rates of mental health issues, addiction, domestic violence, and suicide within Indigenous communities today.

C. Cultural and Linguistic Devastation:

The explicit goal of the boarding schools was cultural genocide, and in many respects, they succeeded in severely damaging Indigenous cultures. Hundreds of languages, repositories of vast traditional knowledge, were silenced, pushing many to the brink of extinction. Sacred ceremonies, spiritual practices, storytelling traditions, and artistic expressions were suppressed. The disruption of traditional knowledge transfer systems meant that entire generations grew up without access to the wisdom of their elders, leading to a profound loss of cultural continuity.

D. Socio-Economic Disadvantage:

The vocational training provided by the schools often prepared students for low-wage labor rather than equipping them with skills for self-sufficiency or leadership within their own communities. The lack of quality academic education further disadvantaged Native Americans in the broader economy. Combined with the psychological impacts, this contributed to cycles of poverty and marginalization that persist in many Indigenous communities.

E. Erosion of Tribal Sovereignty and Self-Determination:

By attacking the cultural and familial foundations of tribal nations, the boarding school system aimed to undermine their inherent sovereignty and ability to govern themselves. The forced assimilation policies were part of a larger strategy to dismantle tribal governments and seize Native lands, leaving a lasting legacy of distrust between Indigenous peoples and the U.S. government.

IV. Resistance, Resilience, and Reconciliation

Despite the overwhelming pressures, Native American children and communities displayed remarkable resilience. Many children resisted in small ways—speaking their language in secret, practicing traditions when they could, or running away (often facing severe punishment if caught). Communities, though devastated, continued to fight for their children and preserve their cultures.

The boarding school era began to wane in the mid-20th century, largely due to changing federal policies, growing recognition of the schools’ failures, and increased advocacy by Native American leaders and allies. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 marked a shift away from forced assimilation, and subsequent legislation, like the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, aimed to protect Native children and families. The last federally operated boarding schools closed in the late 20th century, though some mission schools persisted longer.

In recent decades, there has been a growing movement towards truth, healing, and reconciliation. Indigenous communities are actively working to revitalize their languages and cultures, reclaim their histories, and support survivors and their descendants. Efforts include documenting survivor testimonies, repatriating remains of children who died at the schools, and advocating for governmental apologies and reparations. The U.S. Department of the Interior’s "Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative" launched in 2021, aims to conduct a comprehensive review of the legacy of these schools, mirroring similar efforts in Canada (Truth and Reconciliation Commission).

V. Conclusion

The Native American boarding school system represents a profound moral failure and a deliberate act of cultural genocide. Its history is not merely a collection of isolated incidents but a systemic policy that inflicted deep and enduring wounds on Indigenous peoples. Understanding this history is crucial not only for acknowledging past injustices but also for comprehending the contemporary challenges faced by Native American communities. True reconciliation requires not just an apology but a sustained commitment to supporting Indigenous self-determination, cultural revitalization, and healing, ensuring that the lessons learned from this dark chapter guide a more just and equitable future.