The National Museum of the American Indian: A Beacon of Indigenous Cultures

When discussing the largest Native American museum, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) unequivocally stands as the preeminent institution. Part of the Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, the NMAI is unique in its scale, scope, and foundational philosophy. It is not merely a repository of objects but a dynamic cultural center dedicated to the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of Native Americans of the Western Hemisphere. Its significance extends beyond its impressive collections, rooted deeply in a revolutionary approach to museology that centers Indigenous voices and perspectives.

A New Vision: From "Vanishing Race" to Living Cultures

For centuries, museums often presented Native American cultures through a lens of exoticism, colonialism, or as relics of a "vanishing race." Collections were frequently amassed without adequate consultation, and narratives were predominantly crafted by non-Native scholars. The establishment of the NMAI marked a profound departure from this historical trajectory. Its very genesis was an act of recognition and rectification, aiming to redefine how Indigenous peoples are represented and understood on a national and international stage.

The NMAI’s origins trace back to the vast collection of George Gustav Heye, a wealthy New Yorker who amassed over a million Native American artifacts between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries. His Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, opened in New York City in 1922. While groundbreaking for its time, Heye’s approach, like many collectors of his era, was often extractive, acquiring objects with little consideration for Indigenous protocols or cultural sensitivities.

The pivotal moment arrived with the passage of the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989. This landmark legislation mandated the transfer of the Heye Foundation’s collections to the Smithsonian Institution and, crucially, called for the establishment of a new national museum dedicated to the Native peoples of the Americas. This act was not just about acquiring a collection; it was about rectifying historical injustices, promoting self-determination, and empowering Native communities to tell their own stories. A key provision of the act, influenced by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990, also enshrined the principle of repatriation – the return of human remains and sacred objects to their descendant communities.

The NMAI’s Revolutionary Philosophy

What sets the NMAI apart and makes it truly the largest in spirit, if not solely by physical footprint, is its core philosophy, built on four foundational pillars:

- Collaboration and Consultation: Unlike traditional museums, the NMAI operates on a principle of deep and ongoing collaboration with Native communities. From exhibition development and artifact interpretation to research and public programming, Indigenous voices are central. This ensures that the narratives presented are authentic, respectful, and reflective of diverse tribal perspectives, moving beyond monolithic portrayals of "Native Americans."

- Focus on Living Cultures: The museum actively counters the historical tendency to portray Native cultures as static or belonging only to the past. It celebrates the vibrancy, resilience, and contemporary relevance of Indigenous peoples, showcasing modern art, activism, language revitalization efforts, and ongoing cultural practices. This commitment to the present and future is evident in its programming and exhibitions.

- Ethical Stewardship and Repatriation: The NMAI is a leader in ethical museum practices, particularly concerning the repatriation of ancestral remains and sacred objects. Its commitment to NAGPRA and other international guidelines demonstrates a profound respect for cultural patrimony and a dedication to healing historical wounds. This process involves meticulous research, respectful dialogue with tribal representatives, and the physical return of items deemed culturally significant.

- De-colonizing Museology: The NMAI actively challenges traditional Western museum paradigms. It questions conventional notions of authority, ownership, and interpretation, striving to create a space where Indigenous epistemologies and worldviews are honored and shared on their own terms. This involves innovative exhibition design, the use of Indigenous languages, and a focus on oral traditions.

The Three Pillars: Locations and Their Roles

The NMAI is not a single building but a multi-faceted institution spread across three key locations, each serving distinct yet interconnected purposes:

-

The National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall (Washington, D.C.):

Opened in 2004, this iconic building is the public face of the NMAI. Its architecture, designed by Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot) and others, is deeply symbolic, evoking natural forms like wind-carved rock formations and traditional Native dwellings. It features a curvilinear design, natural light, and indigenous landscaping, creating an immersive and spiritual experience. The museum houses permanent and rotating exhibitions developed in partnership with Native communities, covering a vast array of topics from creation stories and political sovereignty to contemporary art and environmental stewardship. It also hosts numerous public programs, including traditional dances, music performances, culinary festivals, and educational workshops, making it a vibrant cultural hub. The "cafeteria," Mitsitam Cafe, is renowned for offering Indigenous foods from across the Americas, further engaging visitors with Native cultures through taste. -

The George Gustav Heye Center (New York City):

Located within the historic Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in Lower Manhattan, this center opened in 1994. It occupies a grand Beaux-Arts building and serves a diverse urban audience. The Heye Center often features smaller, more focused exhibitions, drawing from the museum’s extensive collections to explore specific themes, artists, or regions. Its programming caters to New York’s vibrant cultural scene, offering a dynamic space for performances, film screenings, and educational initiatives. While the D.C. museum focuses on a broader national narrative, the Heye Center often provides a more intimate and detailed look at particular aspects of Native American heritage. -

The Cultural Resources Center (Suitland, Maryland):

Opened in 1999, the CRC is the intellectual and logistical heart of the NMAI. This state-of-the-art facility is not typically open to the general public but serves as the primary collections management, conservation, and research center. It houses the vast majority of the NMAI’s approximately 825,000 objects, 12,000 linear feet of archival materials, and a substantial library. Here, conservators work to preserve artifacts, researchers delve into the collections, and, crucially, repatriation efforts are meticulously carried out. The CRC embodies the museum’s commitment to responsible stewardship, ensuring the long-term preservation of Indigenous cultural heritage and facilitating its study and return to descendant communities.

The Scope and Scale of the Collections

The NMAI’s collection is unparalleled in its breadth and depth, encompassing a staggering array of objects from virtually every Native culture in the Western Hemisphere. It includes archaeological treasures, ethnographic artifacts, historical documents, contemporary art, and ceremonial objects. The collection spans over 12,000 years of history, representing more than 1,200 Indigenous cultures from the Arctic to Patagonia.

The diversity of the collection is remarkable:

- Archaeological artifacts: Tools, pottery, textiles, and adornments providing insights into ancient civilizations.

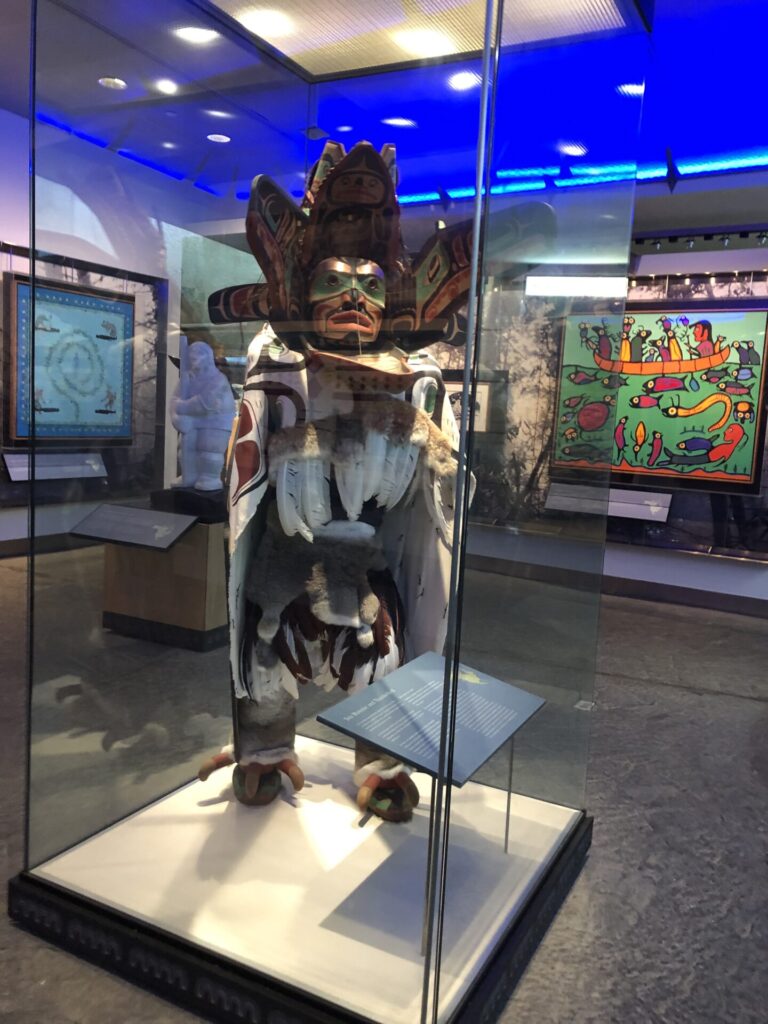

- Ethnographic materials: Clothing, ceremonial regalia, household items, and hunting implements reflecting daily life and cultural practices.

- Contemporary art: Paintings, sculptures, photographs, and mixed media installations by leading Indigenous artists, showcasing the vitality of modern Native expression.

- Photographic and archival collections: Thousands of historical images and documents that offer invaluable records of Native lives and historical events.

- Sacred objects: Items of deep spiritual significance, many of which are part of ongoing repatriation efforts.

This vast and varied collection, meticulously documented and cared for, serves as an invaluable resource for Native communities, scholars, and the public alike. It provides tangible links to ancestral traditions, fosters cultural pride, and offers profound insights into the human experience.

Impact and Enduring Significance

The National Museum of the American Indian has had a transformative impact since its inception. It has:

- Elevated Indigenous voices: Providing a national platform for Native peoples to tell their own stories, challenge stereotypes, and assert their sovereignty.

- Educated millions: Serving as a vital educational resource for both Native and non-Native audiences, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of Indigenous cultures.

- Influenced museology globally: Becoming a model for ethical museum practices, particularly in the areas of collaboration, repatriation, and de-colonization.

- Promoted cultural revitalization: By showcasing contemporary Native arts and traditions, it inspires and supports cultural continuity and innovation within Indigenous communities.

- Fostered reconciliation: By acknowledging historical injustices and actively working towards restitution, the NMAI contributes to a broader process of healing and reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and settler societies.

In conclusion, the National Museum of the American Indian is far more than just the largest Native American museum in terms of its collection size or physical presence. It represents a paradigm shift in the cultural landscape, embodying a profound commitment to Indigenous self-determination, ethical stewardship, and the vibrant celebration of living cultures. Through its three distinct yet interconnected sites, its vast collections, and its revolutionary philosophy, the NMAI stands as a powerful testament to the enduring legacy and dynamic future of Native peoples throughout the Western Hemisphere. It is an indispensable institution for anyone seeking to understand the rich, complex, and vital tapestry of Indigenous America.