The Sophisticated Agricultural Practices of Early Native American Tribes

The conventional image of early Native American life often focuses on hunting and gathering, inadvertently overshadowing the profound agricultural achievements that sustained vast populations and fostered complex societies across the Americas. Far from being primitive, the agricultural practices developed by indigenous peoples were remarkably sophisticated, sustainable, and deeply integrated with their ecological understanding and spiritual worldviews. This article delves into the diverse and ingenious methods employed by early Native American tribes, highlighting their innovations in plant domestication, land management, and sustainable cultivation.

A Tapestry of Agricultural Diversity Across Continents

It is crucial to recognize that "Native American" encompasses hundreds of distinct tribes across two continents, each adapting their agricultural strategies to unique environmental conditions, from arid deserts to fertile river valleys and dense forests. While Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec developed highly intensive systems, tribes further north also engineered impressive agricultural landscapes.

Major Agricultural Regions and Examples:

- Eastern Woodlands: Tribes like the Iroquois, Cherokee, and Lenape cultivated large fields of maize, beans, and squash, often employing controlled burns to clear land and enrich soil.

- Southwest: Ancestral Puebloans, Hohokam, and Mogollon developed intricate irrigation systems, dry farming techniques, and cultivated drought-resistant varieties of maize, beans, squash, and cotton in arid environments.

- Plains: While many Plains tribes were nomadic bison hunters, some, particularly those along river valleys like the Mandan and Hidatsa, practiced extensive horticulture, growing the "Three Sisters" and sunflowers.

- Pacific Northwest: Though often associated with abundant wild resources, some tribes managed specific plant resources through controlled burning and cultivation of root crops.

The Foundation: Key Cultigens and Their Domestication

The most significant contribution of early Native American agriculture to global food systems is the domestication of an array of staple crops, many of which are now integral to diets worldwide.

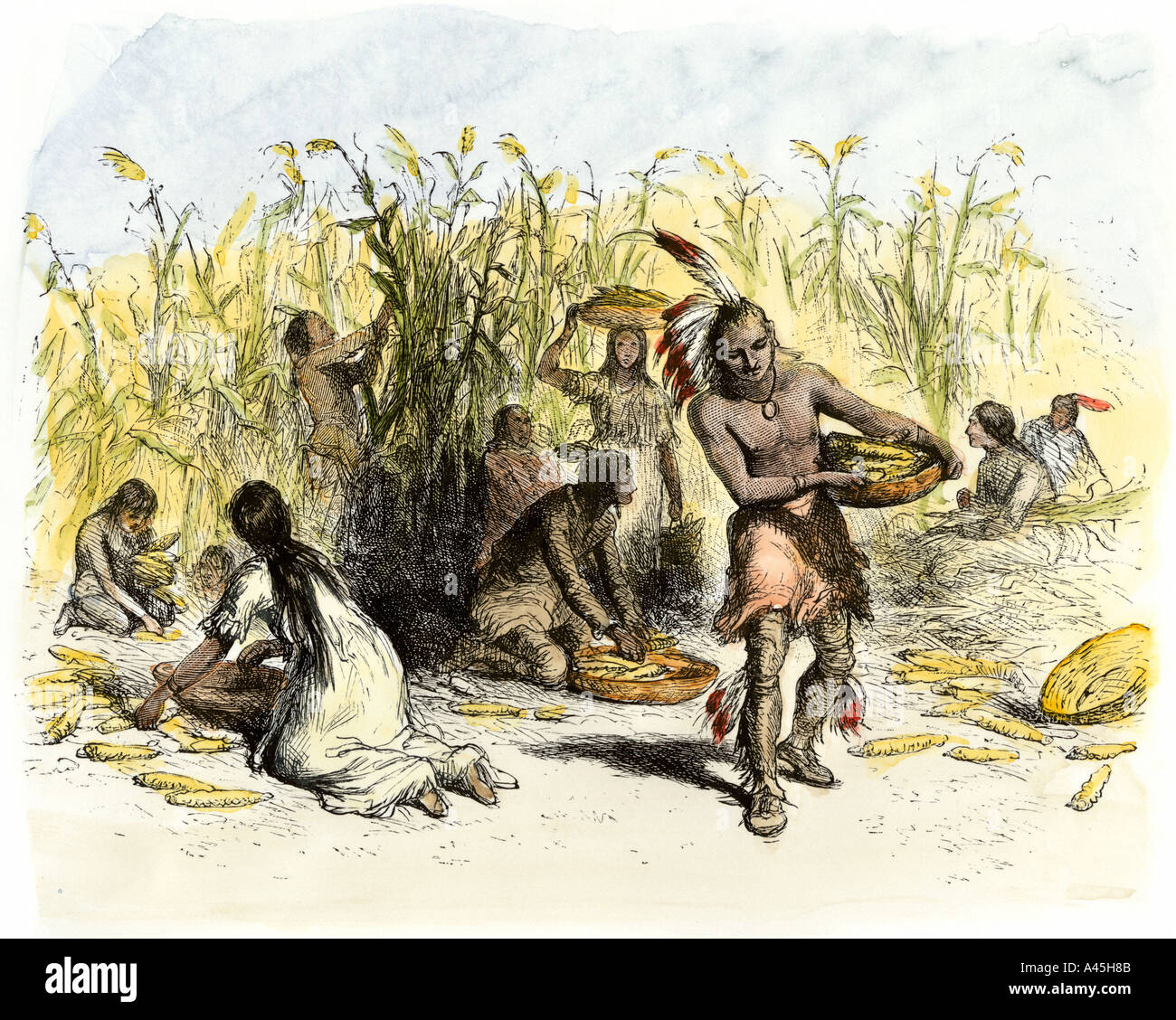

The Three Sisters: Maize, Beans, and Squash

The cornerstone of agriculture for many tribes, particularly in the Eastern Woodlands and Southwest, was the symbiotic planting of maize (corn), beans, and squash, collectively known as the "Three Sisters." This polyculture system was a testament to their deep ecological knowledge:

- Maize (Corn): The central sister, providing a stalk for the beans to climb, eliminating the need for separate poles. Maize was domesticated from teosinte in Mesoamerica over thousands of years, resulting in countless varieties adapted to diverse climates and uses (flour, popping, roasting).

- Beans: The climbing beans utilized the maize stalks for support, growing upwards to access sunlight. Crucially, beans are legumes, meaning their roots host nitrogen-fixing bacteria. These bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants, thereby enriching the soil and naturally fertilizing the heavy-feeding maize.

- Squash: The broad leaves of squash plants spread across the ground, shading the soil. This dense canopy helped suppress weeds by blocking sunlight, conserved soil moisture by reducing evaporation, and deterred pests due to their prickly stems.

This intercropping strategy maximized yield from a given area, maintained soil fertility, and provided a nutritionally complete diet when consumed together (maize for carbohydrates, beans for protein and amino acids, squash for vitamins and minerals).

Beyond the Trinity: Other Vital Crops

While the Three Sisters were foundational, numerous other plants were domesticated or intensively managed:

- Potatoes: Originating in the Andes, potatoes were a primary staple for civilizations in South America, demonstrating incredible genetic diversity and adaptation to high altitudes.

- Sunflowers: Cultivated for their oil-rich seeds, which provided fat and protein, and their stalks used for construction.

- Amaranth and Quinoa: Highly nutritious pseudo-cereals, rich in protein and micronutrients, vital in parts of Mesoamerica and the Andes.

- Tobacco: Cultivated extensively for ceremonial, medicinal, and social purposes, highlighting its cultural significance beyond mere consumption.

- Cotton: Grown in the Southwest for textiles, demonstrating advanced textile production.

- Chilies: Used extensively as a spice and for medicinal properties.

- Wild Rice (Zizania aquatica): While technically a wild grain, tribes around the Great Lakes (e.g., Ojibwe) engaged in sophisticated management practices, including seeding, harvesting, and protection, blurring the lines between gathering and cultivation.

Ingenious Cultivation Techniques

Early Native American farmers employed a range of sophisticated techniques to optimize crop growth, manage resources, and ensure long-term sustainability.

1. Soil Management and Fertility

- Slash-and-Burn (Swidden Agriculture): Often misunderstood as destructive, this was a carefully controlled method, particularly in forested regions. Small patches of forest were cleared, and the dried vegetation was burned. The ash released vital nutrients (potassium, phosphorus) into the soil, temporarily boosting fertility and reducing soil acidity. This was typically part of a long fallow rotation, allowing the forest to regenerate before the cycle repeated, ensuring ecological balance.

- Fish Fertilization: Along coastal areas and rivers, tribes like the Wampanoag were observed by early European settlers placing a fish (e.g., alewife, herring) in each maize hill. The decomposing fish provided a rich source of nitrogen and other nutrients.

- Composting and Green Manure: Though not always explicitly documented, the practice of burying organic matter, leaving crop residues, and intercropping nitrogen-fixing plants effectively acted as forms of composting and green manuring, enriching the soil over time.

- Mounds and Ridges: Planting on raised mounds improved drainage, warmed the soil, and facilitated planting in areas prone to flooding.

2. Water Management

In arid and semi-arid regions, water management was paramount, leading to remarkable engineering feats:

- Irrigation Systems: The Hohokam in present-day Arizona constructed vast networks of canals spanning hundreds of miles, diverting water from rivers to irrigate fields. The Ancestral Puebloans developed sophisticated systems of check dams, diversion dams, and terraces to capture and channel rainwater, preventing erosion and maximizing water penetration.

- Dry Farming: In areas without reliable water sources, techniques like planting seeds deeply to access residual moisture, using deep soil amendments, and selecting drought-resistant crop varieties were crucial. "Waffle gardens" in the Southwest, small sunken plots surrounded by earthen walls, helped collect and retain precious rainwater.

- Floodplain Agriculture: Tribes along major rivers (e.g., Missouri River) utilized the natural annual flooding to deposit nutrient-rich silt onto their fields, naturally fertilizing the land.

3. Tools and Tillage

Native American farmers developed effective tools from available materials:

- Digging Sticks: Simple yet versatile tools for breaking ground, planting seeds, and harvesting root crops.

- Hoes: Fashioned from wood, bone, shell, or stone (like scapula hoes from bison shoulder blades), these were used for weeding, hilling, and soil preparation.

- Minimal Tillage: Many practices involved minimal soil disturbance, which helped preserve soil structure, retain moisture, and prevent erosion – principles now recognized in modern conservation agriculture.

4. Pest and Disease Management

- Companion Planting: The Three Sisters system itself was a form of pest management, with the diverse planting reducing the likelihood of widespread pest infestations common in monocultures.

- Biodiversity: Maintaining diverse ecosystems around agricultural fields provided habitat for natural predators of pests.

- Manual Removal: Constant vigilance and manual removal of pests were common practices.

- Seed Selection: Over generations, farmers selected for disease-resistant and pest-tolerant varieties.

5. Seed Saving and Selection

A cornerstone of their agricultural success was the meticulous practice of seed saving. Farmers carefully selected the best seeds from the most robust plants each season, ensuring that desirable traits were passed on. This continuous selection process led to the development of highly adapted and resilient crop varieties perfectly suited to local conditions and cultural preferences.

Agroforestry and Landscape Management

Beyond field agriculture, many tribes practiced sophisticated forms of agroforestry and landscape management:

- Controlled Burns: Beyond field preparation, controlled burns were used to manage entire forest ecosystems. They reduced underbrush, prevented catastrophic wildfires, encouraged the growth of desired plant species (e.g., berries, nuts, medicinal plants), created open areas for game animals, and facilitated travel.

- Forest Gardens: Rather than clearing vast tracts, many tribes integrated cultivated plants within existing forest ecosystems, creating "food forests" that mimic natural patterns while providing diverse food sources. They managed wild fruit trees, nut trees, and medicinal plants, enhancing their productivity without destroying the forest structure.

The Ethos of Sustainability and Reciprocity

Underlying all these practices was a profound philosophical and spiritual connection to the land and its resources. Native American agriculture was not merely a means of sustenance but an act of reciprocity and gratitude:

- Respect for Nature: The land was seen as a living entity, a mother, not a resource to be exploited. Harvesting was often accompanied by prayers and offerings.

- Long-Term Perspective: Decisions were made with consideration for future generations (often "seven generations"), emphasizing sustainability and stewardship over short-term gain.

- Community-Centric: Agricultural labor was often a communal effort, strengthening social bonds and ensuring equitable distribution of resources.

- Deep Ecological Knowledge: Their practices were based on thousands of years of observation, experimentation, and intimate understanding of local ecosystems, climate patterns, and plant behavior.

Societal Impact and Legacy

The development of agriculture had a transformative impact on early Native American societies:

- Sedentary Lifestyles: The ability to produce surplus food allowed for permanent settlements, leading to the development of villages, towns, and eventually cities.

- Population Growth: A reliable food supply supported larger and denser populations.

- Social Complexity: Increased food security allowed for specialization of labor, the emergence of hierarchical social structures, and the development of art, religion, and complex governance systems.

- Trade Networks: Agricultural surpluses facilitated extensive trade networks, connecting distant communities.

The legacy of early Native American agricultural practices is immense. They domesticated many of the world’s most important food crops, developed innovative and sustainable farming techniques, and demonstrated a profound understanding of ecological balance. Their methods offer invaluable lessons for modern agriculture, particularly in an era grappling with climate change, food security, and the need for more sustainable food production systems. Recognizing and appreciating this rich history is essential for a holistic understanding of both human ingenuity and our enduring relationship with the natural world.