Contemporary Issues Facing Native American Artists: A Comprehensive Analysis

Native American art, encompassing a vast spectrum of artistic expressions from over 574 federally recognized tribes and numerous unacknowledged Indigenous communities across the United States, is a vibrant and evolving testament to enduring cultures, spiritual beliefs, and historical resilience. From ancient petroglyphs and intricate pottery to contemporary multimedia installations and digital art, Indigenous artistic traditions have continuously adapted and innovated. However, despite this rich legacy and ongoing dynamism, Native American artists today confront a complex array of contemporary issues rooted in historical injustices, economic disparities, cultural misunderstandings, and the pervasive effects of colonialism. These challenges critically impact their ability to create, disseminate, and profit from their work, while also shaping the very discourse surrounding Indigenous art.

This analysis delves into the multifaceted issues facing Native American artists, examining them through the lenses of identity and authenticity, market dynamics and economic exploitation, representation and stereotypes, cultural preservation and intellectual property, and the ongoing struggle for decolonization within the art world.

I. Identity, Authenticity, and Self-Definition

One of the most profound and frequently debated issues centers on questions of identity and authenticity in Native American art. The very definition of who constitutes a "Native American artist" and what constitutes "authentic" Native art is fraught with historical baggage and contemporary complexities.

A. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act (IACA) of 1990: While intended to protect Native American artists and consumers from fraudulent reproductions, the IACA defines "Indian" as a member of a federally or state-recognized tribe, or an individual certified as an Indian artist by a tribal council. This legal framework, while providing a measure of protection, inadvertently sparks internal debates about blood quantum, tribal enrollment, and cultural affiliation. Artists who may identify strongly with their Indigenous heritage but do not meet these specific legal criteria often face challenges in marketing their work as "Native American art," leading to feelings of exclusion and a rigidification of identity that can overlook the diverse lived experiences of Indigenous peoples.

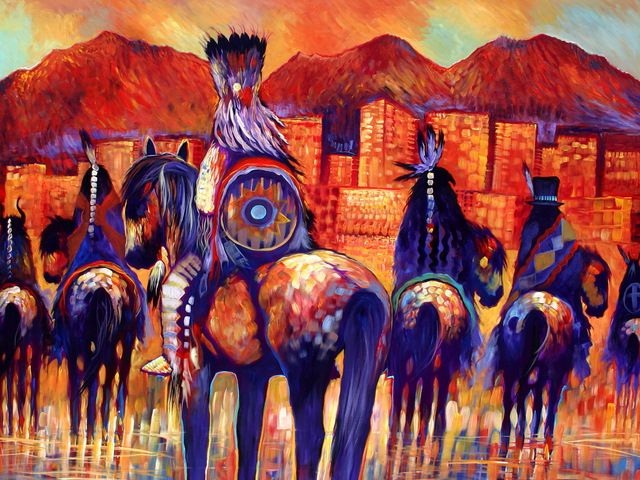

B. "Traditional" vs. "Contemporary" Dichotomy: A pervasive challenge is the expectation that Native art must conform to "traditional" aesthetics, often trapping artists in historical stereotypes. Many collectors, gallerists, and even the general public implicitly expect Native art to be "authentic" by appearing ancient or tied to specific historical forms (e.g., pottery, weaving, beadwork with specific motifs). This creates a false dichotomy that marginalizes contemporary Native artists who explore abstract forms, conceptual art, installation, digital media, or who integrate Western art historical influences into their practice. Their work is sometimes dismissed as "not Indian enough," undermining their artistic freedom and innovation. Artists are often forced to navigate a market that values historical continuity over creative evolution, perpetuating the "past tense" perception of Indigenous cultures.

C. Self-Definition and Sovereignty in Art: Increasingly, Native American artists assert their right to define their own identities and artistic expressions without external imposition. This includes challenging notions of "authenticity" that are often dictated by non-Native institutions or market demands. Artists are reclaiming narratives and using their art to explore complex themes of colonialism, environmental justice, gender identity, and urban Indigenous experiences, thereby broadening the scope of what Native American art can be.

II. Market Dynamics, Exploitation, and Appropriation

The economic landscape for Native American artists is often characterized by systemic inequalities, leading to exploitation and limited access to mainstream art markets.

A. Counterfeit Goods and "Fake Indian Art": The market is flooded with mass-produced, non-Native-made items falsely marketed as "Native American" art or crafts. This widespread fraud not only misleads consumers but severely undercuts the economic viability of legitimate Native artists. It devalues authentic craftsmanship, cultural knowledge, and the labor involved, making it difficult for Native artists to command fair prices for their work. The IACA, while a crucial tool, faces challenges in enforcement and public awareness.

B. Cultural Appropriation: Beyond outright fraud, cultural appropriation remains a significant issue. Non-Native artists, designers, and corporations frequently borrow or outright steal Indigenous designs, symbols, stories, and spiritual elements without understanding their cultural significance, acknowledging the originators, or providing compensation. This act of appropriation not only disrespects sacred traditions but also exploits the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples for commercial gain, often trivializing profound spiritual or communal meanings. It further denies Native artists the economic benefits and recognition due to their own cultural innovations.

C. Limited Access and Representation in Mainstream Markets: Native American art is often relegated to specialized "Native American art" sections or specific galleries, rather than being integrated into the broader contemporary art world. This segregation limits visibility, critical engagement, and opportunities for cross-cultural dialogue. Non-Native curators, gallerists, and collectors often act as gatekeepers, sometimes perpetuating stereotypes or failing to understand the nuances of Indigenous artistic practices. Furthermore, Native artists often lack the robust institutional support, marketing resources, and networks available to their non-Native counterparts.

III. Representation, Stereotypes, and Visibility

The way Native American art and artists are perceived by the wider public is heavily influenced by historical misrepresentations and pervasive stereotypes.

A. The "Vanishing Indian" and "Noble Savage" Tropes: Historically, Native American art was often collected and displayed in anthropological museums as artifacts of a "vanishing race," rather than as living, evolving artistic expressions. This perpetuated the myth that Indigenous cultures were static, confined to the past, and incapable of contemporary innovation. While this has begun to shift, the legacy of these tropes still influences how Native art is interpreted, often prioritizing ethnographic value over artistic merit.

B. Lack of Critical Engagement: Mainstream art criticism and scholarship have historically paid insufficient attention to contemporary Native American art. This lack of robust critical discourse limits the intellectual and theoretical development surrounding Indigenous art, hindering its integration into broader art historical narratives. It also denies Native artists the kind of thoughtful analysis and recognition that non-Native artists often receive.

C. Tokenism and Surface-Level Inclusion: While there has been an increased effort towards diversity in the art world, Native American artists can sometimes experience tokenism – being included in exhibitions or collections primarily to fulfill diversity quotas, rather than due to a deep engagement with their work or perspective. This can lead to superficial representation without genuine institutional change or sustained support.

IV. Cultural Preservation, Revitalization, and Intellectual Property

Native American artists are often at the forefront of efforts to preserve and revitalize their cultural heritage, facing specific challenges related to traditional knowledge and materials.

A. Loss of Traditional Knowledge and Languages: The intergenerational transmission of artistic techniques, cultural stories, and ceremonial protocols is vital for many Indigenous art forms. Historical traumas, including forced assimilation through boarding schools, have severely disrupted this transmission, leading to the loss of languages and traditional knowledge systems that underpin many art practices. Artists often take on the crucial role of cultural educators and knowledge keepers, often without adequate resources or recognition.

B. Access to Traditional Materials and Environmental Concerns: Many Indigenous art forms rely on specific natural materials (e.g., particular clays, plant fibers, animal hides, dyes). Environmental degradation, climate change, and restricted access to ancestral lands due to resource extraction or land dispossession threaten the availability of these materials, forcing artists to adapt, find alternatives, or cease certain practices.

C. Protection of Communal Intellectual Property: Unlike Western intellectual property law, which often focuses on individual ownership, many Indigenous cultures view knowledge, designs, and stories as communal property, passed down through generations and held in trust for the community. Western copyright law is often inadequate to protect this communal intellectual property, making it difficult for tribes and artists to prevent the unauthorized use or appropriation of sacred or culturally sensitive designs and narratives. Efforts are ongoing to develop legal frameworks that better accommodate Indigenous customary law.

V. Decolonization, Sovereignty, and Institutional Critique

A foundational issue underpinning all others is the ongoing process of decolonization within the art world. This involves challenging the colonial structures, narratives, and power dynamics that have historically shaped the production, display, and interpretation of Native American art.

A. Challenging Colonial Narratives in Institutions: Museums and galleries are increasingly being pushed to decolonize their collections, exhibitions, and interpretative frameworks. This means moving beyond presenting Indigenous art solely through an ethnographic lens, repatriating cultural objects, and incorporating Indigenous voices and perspectives into all aspects of institutional practice. Native American artists and scholars are advocating for greater Indigenous control over curatorial decisions, exhibition narratives, and institutional leadership.

B. Art as a Tool for Sovereignty and Resistance: Many contemporary Native artists use their work as a powerful means of asserting tribal sovereignty, challenging colonial legacies, protesting injustices (such as land dispossession, environmental racism, and violence against Indigenous women), and promoting cultural resurgence. Their art often serves as a form of political activism, cultural affirmation, and historical redress.

Conclusion

The contemporary issues facing Native American artists are deeply interconnected and rooted in the historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism. From the complexities of identity and authenticity to the economic exploitation of their cultural heritage and the pervasive effects of misrepresentation, these challenges demand systemic change and concerted efforts from within and outside Indigenous communities.

Despite these formidable obstacles, Native American artists continue to innovate, create, and thrive. They are at the forefront of cultural revitalization, using their art to preserve traditional knowledge, assert political sovereignty, challenge dominant narratives, and envision decolonized futures. The path forward requires increased education and awareness about Indigenous cultures and art forms, robust legal protections against appropriation and fraud, equitable access to mainstream art markets, greater Indigenous control over cultural institutions, and a profound shift in how Native American art is perceived, valued, and integrated into the global art discourse. By understanding and addressing these critical issues, we can better support the vibrant and essential contributions of Native American artists to the tapestry of human creativity.