Exhibits on the Forced Assimilation of Native Americans: A Comprehensive Exploration

The forced assimilation of Native Americans by European colonizers and the subsequent United States government represents one of the darkest chapters in North American history. Driven by ideologies of Manifest Destiny, racial superiority, and a desire for land and resources, policies were enacted to systematically dismantle Indigenous cultures, languages, spiritual practices, and social structures. Today, museums, cultural centers, and educational institutions play a crucial role in confronting this painful legacy through thoughtfully curated exhibits. These exhibits serve not only as repositories of historical truth but also as platforms for remembrance, healing, and the ongoing struggle for Indigenous sovereignty and cultural revitalization.

The Historical Imperative: Understanding Forced Assimilation

To appreciate the significance of these exhibits, one must first grasp the depth and breadth of the assimilation policies. Beginning in the early 19th century and intensifying after the Civil War, the U.S. government, often in conjunction with religious organizations, implemented a multi-pronged strategy to "civilize" Native Americans. Key mechanisms included:

- Indian Boarding Schools: Perhaps the most notorious instrument of assimilation, these off-reservation residential schools aimed to "kill the Indian, save the man." Children, often forcibly removed from their families, were stripped of their traditional clothing, forbidden to speak their native languages, given new English names, and subjected to harsh discipline, manual labor, and cultural indoctrination. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879, served as a model for dozens of similar institutions across the country.

- Land Allotment (Dawes Act of 1887): This legislation broke up communally held tribal lands into individual plots, a concept antithetical to most Indigenous land tenure systems. The "surplus" land was then sold to non-Native settlers, leading to massive land loss and the destruction of traditional economies.

- Suppression of Cultural and Religious Practices: Traditional ceremonies, dances, spiritual gatherings, and language use were outlawed or severely discouraged. This was an attempt to eradicate Indigenous identity and replace it with Euro-American norms.

- Citizenship and Legal Status: Native Americans were initially denied U.S. citizenship, existing in a liminal legal space. While the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship, it did not always confer full rights or alleviate the pressures of assimilation.

The cumulative impact of these policies was devastating, leading to profound intergenerational trauma, loss of language and cultural knowledge, and economic disenfranchisement. Yet, Indigenous peoples demonstrated remarkable resilience, often practicing their traditions in secret and passing on knowledge despite immense pressure.

The Evolving Landscape of Exhibition: From Colonial Narratives to Indigenous Voices

Early museum exhibits about Native Americans often reflected prevailing colonial attitudes, portraying Indigenous cultures as "primitive" or "vanishing." Artifacts were displayed as curiosities, often decontextualized, and narratives were almost exclusively told from a non-Native perspective.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a profound shift. Fueled by Indigenous activism, scholarship, and self-determination movements, contemporary exhibits strive for:

- Authenticity and Accuracy: Challenging stereotypes and presenting nuanced, historically informed narratives.

- Indigenous Voice and Authority: Prioritizing the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of Native communities themselves, often through collaborative curation.

- Healing and Reconciliation: Recognizing the trauma of the past and fostering spaces for dialogue, understanding, and collective healing.

- Contemporary Relevance: Connecting historical injustices to ongoing issues of Indigenous rights, cultural revitalization, and sovereignty.

Core Thematic Elements in Exhibits on Forced Assimilation

Exhibits tackling forced assimilation typically explore several interconnected themes, employing diverse methodologies to engage visitors:

-

The Boarding School Experience: This is often a central focus. Exhibits feature:

- Personal Testimonies: Oral histories, written accounts, and recorded interviews with survivors provide poignant, first-hand narratives of the emotional, psychological, and physical abuses endured, as well as acts of resistance.

- Artifacts: Original school uniforms (often ill-fitting and culturally inappropriate), textbooks, tools used in vocational training, and personal items smuggled in or made by students offer tangible connections to daily life in the schools.

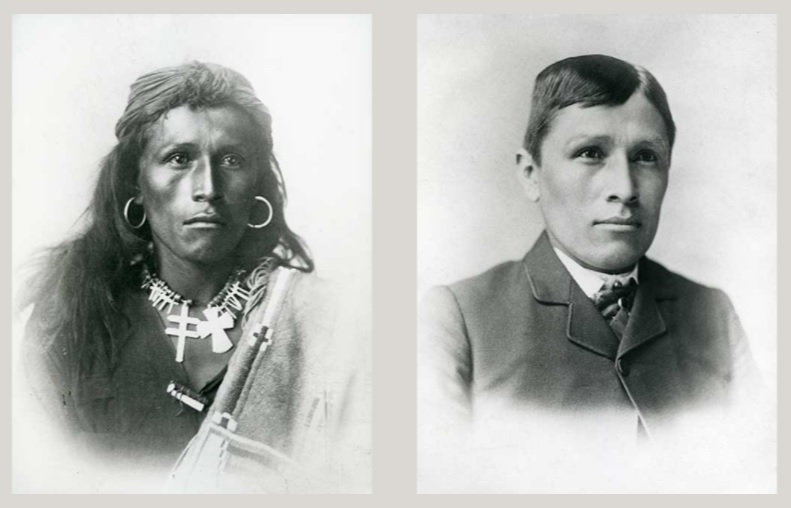

- Before-and-After Photographs: These infamous images, often commissioned by school administrators, depicted students upon arrival in traditional attire and then months later in Western clothing with short hair, serving as stark visual propaganda for the "success" of assimilation. Exhibits now contextualize these images, exposing their manipulative intent.

- Architectural Models/Recreations: Some exhibits utilize models or partial recreations of dormitories, classrooms, or disciplinary spaces to convey the oppressive environment.

-

Cultural Suppression and Resilience: These exhibits highlight what was lost and what endured:

- Language Loss and Revitalization: Displays may feature recordings of endangered languages, historical documents forbidding Indigenous languages, and contemporary efforts at language immersion schools and programs.

- Spiritual and Ceremonial Practices: Artifacts related to traditional ceremonies (e.g., pipes, regalia, sacred objects – displayed with appropriate cultural protocols), historical accounts of their suppression, and contemporary images of revitalized practices.

- Art Forms: Traditional arts like basketry, pottery, weaving, and beadwork, which often encoded cultural knowledge and identity, are showcased as both expressions of cultural continuity and acts of subtle resistance.

-

Land Dispossession and Treaty Violations: Exhibits often use maps, original treaties (and their subsequent violations), government documents, and photographs to illustrate the dramatic loss of Indigenous lands, the breakdown of traditional economies, and the impact on community structures. The legal framework of assimilation, such as the Dawes Act, is explained in detail.

-

Identity, Trauma, and Healing: These exhibits delve into the profound psychological and social impacts of assimilation:

- Intergenerational Trauma: Explanations of how the trauma experienced by boarding school survivors and their parents continues to affect subsequent generations, manifesting in issues like addiction, mental health challenges, and family breakdown.

- Struggles for Identity: Exploring the challenges faced by individuals caught between two cultures, the loss of traditional knowledge, and the ongoing journey of self-discovery.

- Pathways to Healing: Showcasing contemporary Indigenous-led initiatives for healing, cultural reclamation, community rebuilding, and justice.

Methodologies and Curatorial Approaches

Effective exhibits on forced assimilation employ a variety of curatorial strategies:

- Multimedia Integration: Videos, audio recordings, interactive digital displays, and virtual reality experiences immerse visitors in the historical context and personal stories.

- Community Collaboration: Working directly with tribal elders, survivors, and community members ensures that narratives are authentic, respectful, and reflective of Indigenous perspectives. This often involves co-curation, advisory committees, and community input at every stage.

- Emotional Resonance: While maintaining academic rigor, exhibits often aim to evoke empathy and understanding. This might involve creating quiet reflection spaces, using personal narratives as focal points, or presenting challenging truths directly.

- Educational Programming: Complementary educational programs, workshops, and lectures further contextualize the exhibits and provide opportunities for deeper learning and dialogue.

- Restorative Justice Frameworks: Some exhibits are explicitly designed within a restorative justice framework, aiming not just to inform but to contribute to reconciliation and systemic change.

Key Institutions and Examples

While specific exhibits are dynamic, many institutions consistently address this topic:

- The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI): With branches in Washington D.C. and New York City, NMAI is a preeminent institution dedicated to the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of Native Americans. Its permanent and temporary exhibitions frequently explore the impacts of federal policies, including assimilation.

- Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums: Institutions like the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabek Culture and Lifeways (Michigan) or the First Americans Museum (Oklahoma) offer deeply localized and community-specific perspectives on assimilation and resilience, often from the direct descendants of those affected.

- Museums at Former Boarding School Sites: Some former boarding schools, such as the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown University (which houses collections from the former Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School), or the Carlisle Indian Industrial School Project (Pennsylvania), have transformed into sites of remembrance, research, and education, directly confronting their own historical role.

- Traveling Exhibitions: Collaborative efforts often produce traveling exhibits that reach diverse audiences, ensuring wider dissemination of these critical histories.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Creating exhibits on forced assimilation is fraught with challenges:

- Sensitivity and Trauma: The subject matter is deeply painful. Curators must navigate the risk of re-traumatizing survivors and their descendants while accurately portraying the historical truth.

- Authenticity and Voice: Ensuring that Indigenous voices are genuinely central and not tokenized, and that narratives are not appropriated or misrepresented.

- Resource Limitations: Many tribal museums and cultural centers operate with limited funding, impacting their ability to develop and maintain comprehensive exhibits.

- Audience Reception: Addressing a diverse audience, some of whom may be unaware of this history or hold preconceived notions, requires careful pedagogical strategies.

- Repatriation and Cultural Protocols: Ethical considerations around the display of sacred objects, human remains, and culturally sensitive materials must adhere to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and Indigenous cultural protocols.

The Enduring Significance and Future Directions

Exhibits on the forced assimilation of Native Americans are far more than historical displays; they are vital instruments of remembrance, education, and social change. They challenge dominant historical narratives, expose injustices, and honor the resilience of Indigenous peoples. By providing spaces for truth-telling and dialogue, these exhibits contribute to:

- Historical Literacy: Educating the public about a critical, often overlooked, aspect of North American history.

- Decolonization: Actively working to dismantle colonial frameworks within institutions and society.

- Reconciliation: Fostering understanding and empathy necessary for healing historical wounds between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- Cultural Revitalization: Supporting contemporary efforts by Indigenous communities to reclaim and strengthen their languages, traditions, and sovereignty.

Looking forward, the development of these exhibits will likely continue to emphasize Indigenous leadership, digital storytelling, international collaborations (especially with other Indigenous groups globally who experienced similar colonial policies), and a sustained focus on the connections between historical trauma and contemporary social justice issues. These powerful exhibits ensure that the past is not forgotten, and that its lessons inform a more equitable and respectful future.