Indigenous Perspectives on Colonial History: A Decolonial Re-evaluation

Colonial history, as conventionally taught and understood in many parts of the world, often centers on the narratives of European explorers, settlers, and administrators, portraying a linear progression of "discovery," "development," and the eventual integration of "primitive" societies into a "modern" global order. This dominant historical framework frequently marginalizes or entirely omits the voices and experiences of Indigenous peoples, whose lands, cultures, and lives were fundamentally reshaped—and often devastated—by the colonial project. Indigenous perspectives offer a profound and essential counter-narrative, challenging foundational assumptions, re-centering agency, and demanding a decolonial re-evaluation of the past that has profound implications for the present and future.

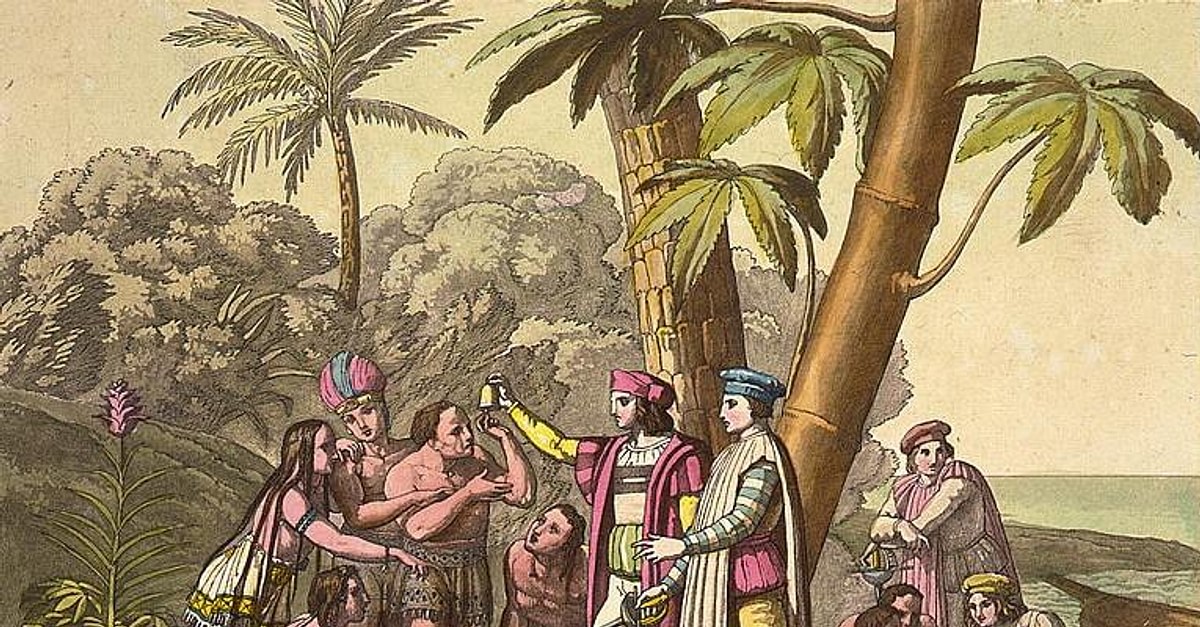

At its core, the Indigenous understanding of colonial history rejects the notion of "discovery" and "settlement." For Indigenous nations, their lands were not empty (terra nullius) or wilderness awaiting civilization, but rather ancestral territories inhabited for millennia, governed by complex social, legal, and spiritual systems. The arrival of European powers was not an encounter but an invasion, marking the beginning of a sustained period of dispossession, violence, and cultural disruption. This re-framing is critical: it shifts the narrative from one of benevolent progress to one of uninvited intrusion and aggressive imposition.

The Land as Pedagogy and Identity

A fundamental divergence between Indigenous and colonial perspectives lies in their understanding of land. Western colonial thought typically views land as property, a commodity to be owned, exploited for resources, and divided for individual profit. Indigenous worldviews, conversely, often conceive of land (and water) as animate, sacred, and inseparable from identity, spirituality, law, and knowledge systems. Land is not merely a resource but a relative, a teacher, and the source of all life and meaning. Dispossession from land, therefore, is not merely an economic loss but a profound spiritual, cultural, and existential wound that severs connections to ancestors, language, ceremonies, and traditional forms of governance.

The imposition of colonial boundaries, private property regimes, and resource extraction industries directly attacked this deep relationality. The forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their territories, the creation of reserves or reservations, and the destruction of traditional ecosystems through mining, logging, and agriculture represent ongoing acts of colonial violence. From an Indigenous standpoint, these actions are not just historical events but continue to manifest as environmental injustice, food insecurity, and the erosion of cultural practices today.

Unceded Sovereignty and the Betrayal of Treaties

Another cornerstone of Indigenous perspectives is the concept of pre-existing and unceded sovereignty. Prior to European contact, Indigenous nations were self-governing entities with their own political structures, legal systems, and diplomatic protocols. Colonial powers often ignored or actively undermined this inherent sovereignty, yet in many instances, they formally recognized it through treaties. However, the interpretation and fulfillment of these treaties diverged dramatically.

For Indigenous nations, treaties were sacred, nation-to-nation agreements outlining shared responsibilities, mutual respect, and the co-existence of distinct peoples. They often involved sharing land and resources, not surrendering them. For colonial powers, treaties were often viewed as a means to legitimize land acquisition, pacify Indigenous resistance, and eventually assimilate Indigenous peoples. The systematic breach of treaty obligations by colonial governments—including the theft of land, denial of promised resources, and suppression of self-governance—is a central theme in Indigenous historical narratives. This betrayal underscores the ongoing struggle for treaty rights and the affirmation of Indigenous sovereignty in contemporary political discourse. The assertion "Our sovereignty was never ceded" resonates across many Indigenous communities globally.

The Enduring Legacy of Colonial Violence and Intergenerational Trauma

Indigenous perspectives illuminate the pervasive and multifaceted violence inherent in the colonial project. This violence was not limited to direct warfare and massacres, though these were tragically common. It extended to cultural genocide through policies of forced assimilation, such as residential or boarding schools, where Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their languages, practice their cultures, or connect with their spiritual traditions. The aim was to "kill the Indian in the child," inflicting profound psychological, emotional, and spiritual damage.

The "Stolen Generations" in Australia, the residential schools in Canada, and similar institutions in the United States and other colonial contexts are not merely historical footnotes but sources of deep, intergenerational trauma. This trauma manifests today in disproportionately high rates of poverty, substance abuse, mental health crises, violence, and incarceration within Indigenous communities. Indigenous historians and scholars emphasize that these contemporary issues are direct consequences of colonial policies, not inherent deficiencies within Indigenous cultures. Understanding this causal link is crucial for developing effective and culturally appropriate solutions.

Resistance, Resilience, and Revitalization

While colonial narratives often depict Indigenous peoples as passive victims, Indigenous perspectives highlight a continuous tradition of resistance and resilience. From initial armed conflicts against invaders to diplomatic efforts to assert treaty rights, from clandestine practice of ceremonies to contemporary land-back movements and political activism, Indigenous peoples have consistently fought for their survival, sovereignty, and cultural integrity.

This resistance takes many forms: the preservation of oral histories, languages, and ceremonies; the development of Indigenous political movements; the assertion of legal rights in national and international forums; and the revitalization of traditional governance structures and knowledge systems. Indigenous scholars are actively decolonizing academia, producing Indigenous-centered histories, epistemologies, and methodologies that challenge Western intellectual hegemony. This ongoing cultural and political revitalization is a testament to the enduring strength and adaptability of Indigenous nations.

Decolonization as an Ongoing Process

For Indigenous peoples, decolonization is not a historical event that concluded with the formal end of a colonial administration. It is an ongoing, complex, and multifaceted process that involves dismantling colonial structures, ideologies, and mindsets within institutions, society, and individual consciousness. It requires the recognition and affirmation of Indigenous self-determination, the repatriation of land, the restoration of traditional governance, and the revitalization of Indigenous languages and cultures.

Decolonization also demands accountability from settler societies and governments for historical injustices and their ongoing impacts. It necessitates a fundamental shift in power dynamics, moving beyond mere inclusion or consultation to genuine partnership and shared sovereignty. This transformative process requires non-Indigenous peoples to critically examine their own inherited biases, privileges, and complicity in colonial systems, and to actively support Indigenous-led initiatives for justice and reconciliation.

Conclusion

Indigenous perspectives on colonial history fundamentally re-orient our understanding of the past. They compel us to move beyond simplistic narratives of progress and development, revealing instead a history marked by invasion, dispossession, violence, and profound injustice. By centering the voices, experiences, and worldviews of Indigenous peoples, we gain a more accurate, ethical, and comprehensive understanding of the forces that have shaped our contemporary world. This perspective is not merely an academic exercise; it is a moral imperative that challenges us to confront uncomfortable truths, acknowledge ongoing harms, and work towards a future founded on justice, respect, and genuine reconciliation. Embracing Indigenous histories is essential for building equitable societies where the inherent rights and sovereignty of all peoples are recognized and upheld.