Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Stewardship: A Holistic and Reciprocal Relationship with the Earth

The escalating global environmental crisis has spurred a critical re-evaluation of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. In this context, Indigenous perspectives on environmental stewardship emerge as a profoundly relevant and often overlooked wellspring of knowledge, practice, and philosophy. Far from being merely a set of conservation techniques, Indigenous stewardship represents a holistic way of life, an intricate web of reciprocal relationships, and an enduring commitment to the well-being of the entire ecological community. This article delves into the foundational principles, practices, and contemporary relevance of Indigenous environmental stewardship, adopting an educational and scientific lens akin to an encyclopedia entry.

I. Defining Indigenous Environmental Stewardship: Beyond Conservation

Indigenous environmental stewardship transcends the Western concept of "conservation," which often implies managing nature for human benefit or protecting pristine wilderness areas from human impact. Instead, Indigenous stewardship is rooted in the understanding that humans are an integral part of nature, not separate from or superior to it. It is a dynamic, intergenerational responsibility to care for the land, water, and all living beings, ensuring their health and vitality for future generations. This stewardship is informed by Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), spiritual beliefs, customary laws, and a deep, place-based intimacy with specific territories.

While diverse across countless Indigenous nations globally—from the Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand) to the Anishinaabeg of North America, the Maasai of East Africa, and the Kayapo of the Amazon—common threads unite these perspectives: a holistic worldview, an ethic of reciprocity, and a profound spiritual and cultural connection to the land.

II. Foundational Principles of Indigenous Stewardship

Several core principles underpin Indigenous approaches to environmental care:

-

A. Holistic Worldview and Interconnectedness:

At the heart of Indigenous stewardship is an understanding of the world as an interconnected web of relationships. All elements—humans, animals, plants, water, air, landforms—are seen as relatives, each possessing spirit and an inherent right to exist. This contrasts sharply with anthropocentric views that place humans at the apex of a hierarchical order. For Indigenous peoples, the health of one component is inextricably linked to the health of all others. Phrases like "All My Relations" (Lakota) or "Whanaungatanga" (Māori, emphasizing kinship and connection) encapsulate this profound sense of relatedness and responsibility. There is no rigid separation between the spiritual and the material, or between humans and nature; all are part of a living, sentient whole. -

B. Spiritual and Cultural Connection to Land (Tūrangawaewae, Country):

Land is not merely property or a resource; it is the source of identity, culture, language, law, and spiritual well-being. For many Indigenous peoples, land is sacred, imbued with ancestral presence and spiritual power. It is a teacher, a provider, and a living entity that holds stories, ceremonies, and historical memory. This deep connection fosters an innate sense of responsibility to protect and nurture it. Dispossession from land is not merely a loss of territory, but a profound severing of cultural and spiritual ties, leading to a loss of identity and well-being. Concepts like "Tūrangawaewae" (Māori, "a place to stand," one’s spiritual and cultural home) or "Country" (Australian Aboriginal, encompassing land, water, sky, and all beings, along with the laws and responsibilities for them) illustrate this fundamental bond. -

C. Reciprocity and Responsibility:

Indigenous stewardship is founded on an ethic of reciprocity. The Earth provides sustenance, knowledge, and life, and in return, humans have a sacred obligation to give back, to care for it, and to show respect. This is not a transactional relationship, but a cyclical one of mutual benefit and respect. Taking from the land is accompanied by ceremonies, prayers, and practices that acknowledge the gift and ensure its renewal. This responsibility extends beyond immediate needs to encompass the well-being of the entire ecosystem. It includes practices like sustainable harvesting, avoiding waste, and actively nurturing biodiversity. -

D. Intergenerational Equity and the Seven Generations Principle:

A hallmark of Indigenous stewardship is its long-term perspective. Decisions are often made with consideration for their impact on "seven generations" into the future, as well as honoring the wisdom of seven generations past. This principle ensures that actions today do not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs or maintain their cultural integrity. It cultivates patience, foresight, and a profound sense of accountability to both ancestors and descendants, promoting sustainability at its core.

III. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in Practice

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is the cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with their environment. TEK is dynamic, place-based, and often deeply embedded in language, stories, ceremonies, and practical skills. It provides the empirical foundation for Indigenous stewardship practices:

-

A. Adaptive Resource Management:

TEK-informed practices often involve sophisticated systems of resource management that are adaptive and localized. Examples include:- Fire Management (Cultural Burning): Indigenous peoples globally have used controlled burning for millennia to manage landscapes, prevent catastrophic wildfires, promote biodiversity, enhance soil fertility, and facilitate the growth of desired plant species. This practice is a crucial tool for ecological health, contrasting with Western fire suppression strategies that can lead to fuel buildup and more destructive fires.

- Sustainable Harvesting: Practices such as rotational hunting, selective fishing, and cyclical plant gathering ensure that populations are not depleted. Protocols dictate when, where, and how much can be taken, often including rules about leaving seed stock, respecting breeding seasons, and sharing harvests.

- Polyculture and Agroforestry: Indigenous agricultural systems, like the "Three Sisters" (corn, beans, squash) practiced by many North American nations, demonstrate advanced ecological understanding, leveraging symbiotic relationships between plants to enhance soil health and yield without external inputs.

-

B. Biodiversity Conservation:

Indigenous communities often inhabit and manage the most biodiverse regions on Earth. Their practices inherently support biodiversity through habitat preservation, sustainable resource use, and a deep understanding of species interactions. The protection of sacred sites often leads to the de facto protection of critical ecosystems. -

C. Water and Land Restoration:

Many Indigenous cultures have elaborate systems for water management, including traditional irrigation, wetland restoration, and practices to maintain water quality. Land restoration efforts often involve revitalizing traditional food systems, reintroducing native species, and healing landscapes damaged by extractive industries.

IV. Challenges and Resilience in the Face of Colonialism

The profound wisdom of Indigenous environmental stewardship has been severely undermined by centuries of colonialism, dispossession, and assimilationist policies. The imposition of Western land tenure systems, resource extraction industries, and a separationist worldview disrupted traditional governance structures, severed Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, and criminalized many stewardship practices (e.g., cultural burning). This has led to environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, and cultural erosion.

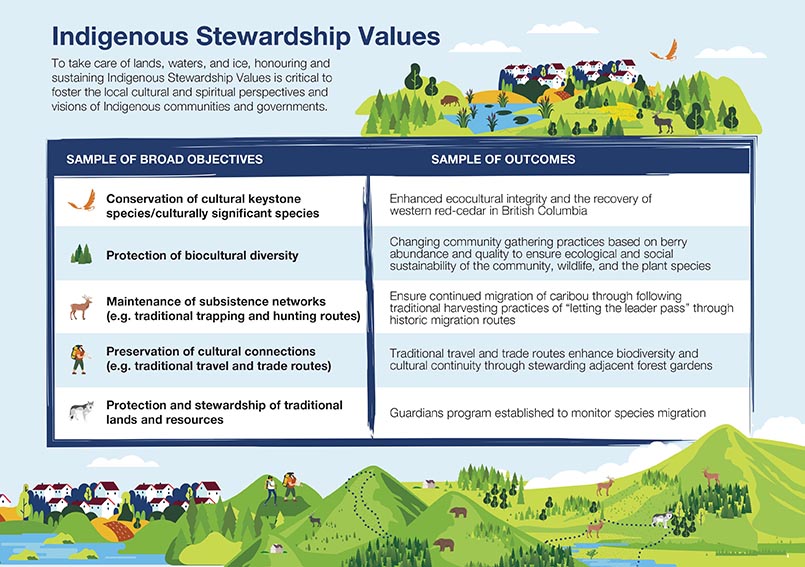

Despite these immense challenges, Indigenous peoples have demonstrated remarkable resilience. There is a global resurgence of Indigenous movements advocating for land rights, self-determination, and the revitalization of traditional ecological knowledge and practices. Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, such as Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), are proving highly effective, often outperforming state-managed protected areas in terms of biodiversity outcomes.

V. Contemporary Relevance and Future Directions

In an era defined by climate change, mass extinction, and environmental degradation, Indigenous perspectives on environmental stewardship are not merely historical curiosities but vital pathways toward a sustainable future.

- Bridging Knowledge Systems: There is a growing recognition of the need to integrate TEK with Western scientific approaches. This synergistic collaboration can lead to more effective conservation strategies, climate adaptation solutions, and sustainable resource management models that are both ecologically sound and culturally appropriate.

- Decolonizing Conservation: A shift is required from a model where Indigenous knowledge is "extracted" or tokenized, to one where Indigenous peoples are recognized as rightful title and rights holders, self-determining partners, and leaders in environmental governance. This involves recognizing Indigenous sovereignty, supporting Indigenous-led conservation, and addressing historical injustices.

- Ethical Frameworks for a Planetary Crisis: Indigenous ethics of reciprocity, intergenerational responsibility, and deep respect for all life offer a powerful antidote to the consumerist and extractive paradigms that have driven environmental destruction. They provide a moral compass for re-envisioning humanity’s place within the living Earth.

Conclusion

Indigenous perspectives on environmental stewardship offer a profound and urgent message: our collective future depends on understanding and honoring the intricate, reciprocal relationship between humanity and the natural world. Far from being a niche concern, this stewardship provides a holistic framework for ecological integrity, social justice, and cultural vitality. By embracing the wisdom of Indigenous peoples—their deep knowledge, their ethical frameworks, and their enduring commitment to Earth—humanity can begin to heal the planet and forge a path toward a truly sustainable and harmonious coexistence. Recognizing, respecting, and empowering Indigenous leadership in environmental governance is not just a matter of justice, but an imperative for the survival and flourishing of all life.