The Enduring Spirit: A Deep Dive into Kickapoo Tribe History and Traditions

The Kickapoo, or "Kiikaapoi" in their own language, meaning "one who moves about" or "stands here and then stands there," are an Algonquian-speaking Indigenous people whose history is marked by extraordinary resilience, adaptability, and a persistent determination to preserve their unique cultural identity despite centuries of displacement and external pressures. From their ancestral homelands in the Great Lakes region to their present-day communities spanning across the United States and Mexico, the Kickapoo narrative is a compelling testament to the strength of a people deeply rooted in their traditions.

Origins and Early Encounters

The Kickapoo trace their origins to the Great Lakes region, specifically the area now encompassing parts of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. As members of the Algonquian linguistic family, they share linguistic and cultural affinities with neighboring tribes such as the Sauk, Fox, Mascouten, and Potawatomi. Their early societies were characterized by a semi-nomadic lifestyle, expertly balancing agriculture with hunting and gathering. They cultivated maize, beans, and squash during the warmer months, establishing settled villages, and then dispersed into smaller hunting camps during the winter to pursue game like deer, bear, and buffalo. This seasonal migration pattern, deeply embedded in their subsistence strategies, likely contributed to their self-description as "those who move about."

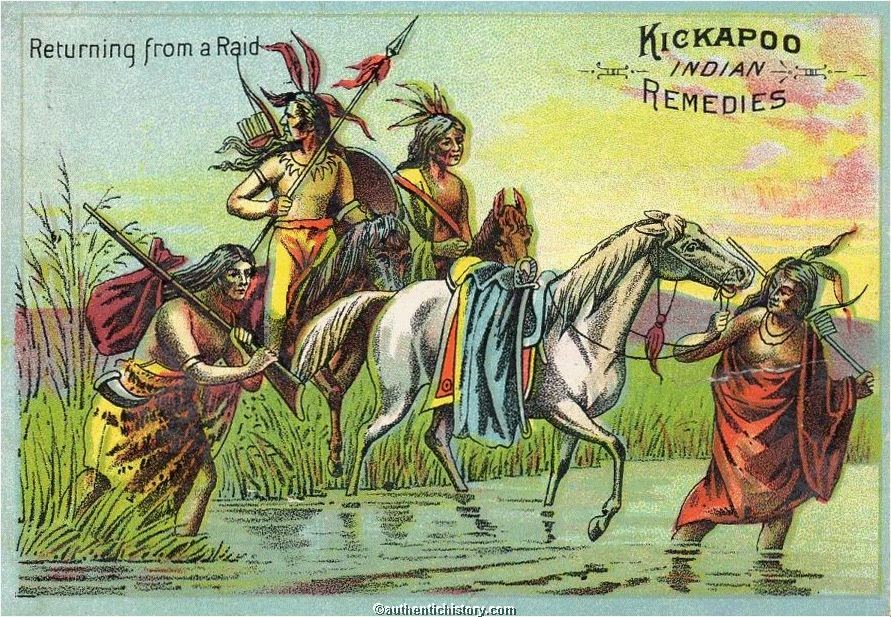

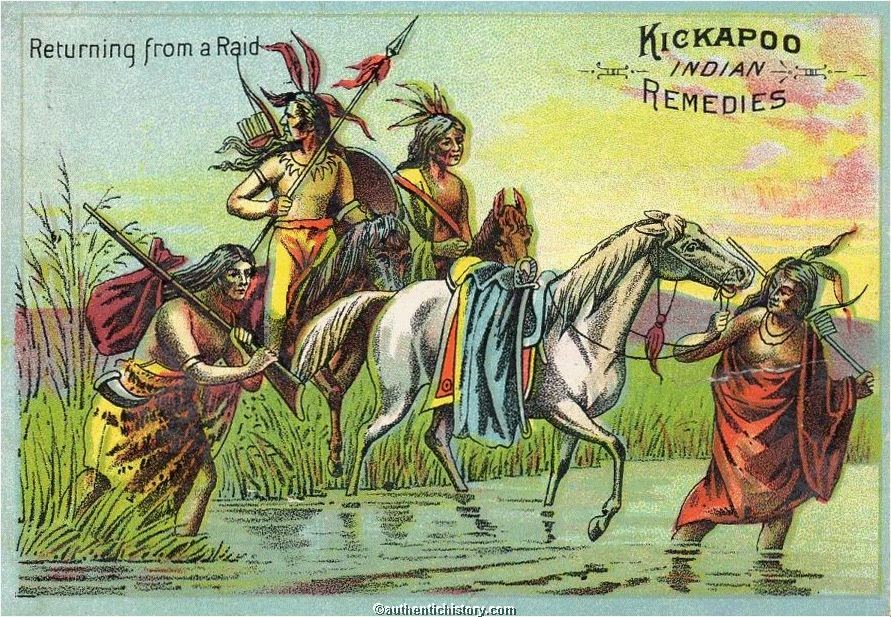

Early European contact, primarily with the French in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, introduced the Kickapoo to trade goods, new technologies, and, unfortunately, devastating diseases. While they engaged in the fur trade, they largely maintained their independence and cultural integrity, often forming alliances with other tribes to resist encroaching colonial powers. Their reputation as fierce warriors and skilled strategists became well-established during these early conflicts, as they fought to protect their territories and way of life.

The Great Migration: A Century of Displacement and Resistance

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a period of profound upheaval for the Kickapoo, characterized by a relentless westward migration driven by Euro-American expansion. Following the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War), British and then American pressures mounted. Unlike many tribes who sought to negotiate treaties and assimilate, a significant faction of the Kickapoo exhibited a staunch refusal to abandon their traditional ways or cede their ancestral lands. This steadfast resistance set them on a unique and arduous journey.

Beginning in Illinois and Indiana, the Kickapoo were subjected to a series of land cessions through treaties, often signed under duress or by unrepresentative leaders. Each treaty pushed them further west – first to Missouri, then to Kansas. However, the Kickapoo, or at least a significant portion of them, consistently resisted assimilation, often leaving designated reservation lands to seek new territories where they could practice their traditional religion and maintain their social structures. This constant movement led them through Oklahoma and Texas, eventually culminating in a remarkable migration into Mexico in the mid-19th century.

The decision to move to Mexico was a deliberate act of cultural preservation. In the 1830s and 1840s, as the United States intensified its removal policies, groups of Kickapoo sought refuge in Mexican territory, often in exchange for acting as a buffer against Apache and Comanche raids. This move allowed them to escape direct U.S. government control and continue their traditional hunting and ceremonial practices relatively undisturbed. This unique diaspora resulted in the formation of distinct Kickapoo communities that exist to this day: the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas, the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas, and the Mascogo (Mexican Kickapoo) community in El Nacimiento, Coahuila, Mexico. Each community, while sharing a common heritage, developed its own adaptations and unique trajectories.

Social Structure and Governance

Kickapoo society was traditionally organized around a patrilineal clan system, where individuals inherited their clan affiliation from their father. Each clan had specific responsibilities and ceremonial duties, contributing to the overall balance and harmony of the community. Leadership was dual, comprising civil chiefs (often elder men respected for their wisdom and ability to mediate disputes) and war chiefs (chosen for their bravery and strategic prowess). Decisions were typically made through consensus in village councils, ensuring that all voices were heard. This decentralized yet cohesive structure allowed for flexibility and adaptability, crucial for their mobile lifestyle.

Traditional Lifeways and Subsistence

The Kickapoo excelled at adapting their subsistence strategies to diverse environments. Their seasonal round involved a cyclical pattern of activity:

- Spring/Summer: Villages were established, often near rivers or fertile lands, where women cultivated extensive gardens of corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. Men would undertake shorter hunting expeditions.

- Autumn: Harvests were gathered, processed, and stored. Community-wide ceremonies, such as the Green Corn Dance, marked this period of abundance.

- Winter: Families or small groups dispersed from the main villages to winter hunting grounds, primarily focusing on deer and buffalo, which provided meat, hides, and bone for tools.

Their dwellings reflected this seasonal mobility. In summer villages, they constructed dome-shaped lodges known as wikiups or waka-gans, made from saplings bent and covered with bark or woven mats. For their winter hunting camps, they often used more substantial rectangular bark houses, providing better insulation against the cold.

Spirituality and Beliefs

At the core of Kickapoo life is a rich and vibrant spiritual tradition, deeply connected to the natural world. Their cosmology centers around the Great Spirit, known as Kiteki or Kicei Manitou, the creator of all things. The Kickapoo believe that all elements of nature – animals, plants, rivers, and stones – possess a spirit and are interconnected. This animistic worldview fosters a profound respect for the environment and a sense of reciprocity with the earth.

Ceremonies are integral to Kickapoo spiritual life, serving to reinforce communal bonds, express gratitude, and seek spiritual guidance. The Green Corn Dance (Pahki-kiwii-na-ka-ne) is one of their most important annual rituals, traditionally held in late summer to celebrate the harvest and renew the community’s spiritual well-being. Other ceremonies include naming rituals, purification rites, and dances that honor specific spirits or significant events. Dreams are also highly valued as a means of receiving messages and guidance from the spirit world, and individuals often seek interpretations from elders or spiritual leaders. Shamans or medicine people play crucial roles in healing, prophecy, and maintaining spiritual harmony.

Material Culture and Arts

Kickapoo material culture reflects their practical ingenuity and aesthetic sensibilities. Women were skilled weavers, creating intricate mats, baskets, and bags from natural fibers like cattail and bulrush. These were used for storage, sleeping, and transporting goods. Beadwork, often featuring geometric designs, adorned clothing, moccasins, and ceremonial items. Men crafted tools and weapons from stone, wood, and bone, and were adept at working with leather for clothing, containers, and shelters. Traditional clothing was made from deerskin, often decorated with quillwork, paint, and later, glass beads. The preservation of these crafts is a vital part of contemporary cultural revitalization efforts.

Language and Cultural Preservation

The Kickapoo language, a Central Algonquian language, is a cornerstone of their identity. Despite centuries of pressure from English and Spanish, it remains actively spoken within the communities, particularly among elders. Efforts are underway to teach the language to younger generations through immersion programs and educational initiatives, recognizing that language loss often precedes cultural erosion.

Contemporary Kickapoo: Resilience and Revitalization

Today, the Kickapoo people continue to thrive across their various communities. The three federally recognized tribes in the United States – the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas, and the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas – maintain sovereign governments, operate businesses (including casinos, which provide vital economic resources), and administer social and cultural programs for their members. They actively engage in self-determination, working to improve education, healthcare, and infrastructure within their communities.

The Mascogo, or Mexican Kickapoo, in El Nacimiento, Coahuila, Mexico, maintain a unique transnational identity, often crossing the U.S. border for work, education, and to visit relatives. They have fiercely guarded their traditional way of life, including their distinct language, ceremonial calendar, and refusal to adopt many modern conveniences, providing a profound example of cultural tenacity.

Despite the geographical separation and varied experiences, a strong sense of shared heritage and kinship connects all Kickapoo people. Contemporary efforts focus on language preservation, cultural education, the perpetuation of ceremonies, and the assertion of tribal sovereignty. The history of the Kickapoo is not merely a tale of displacement but a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to their identity and traditions, demonstrating an enduring spirit that continues to define them.