The Menominee Forest, nestled in northeastern Wisconsin, stands as an unparalleled living testament to the enduring power of indigenous wisdom and sustainable forest management. Spanning approximately 235,000 acres, this forest is not merely a collection of trees but a vibrant, meticulously managed ecosystem that has sustained the Menominee Nation for millennia. Its history and practices offer a profound counter-narrative to conventional resource exploitation, showcasing a holistic approach where ecological health, cultural preservation, and economic prosperity are intricately interwoven. This article delves into the rich history of the Menominee Forest and the sustainable practices that have made it a global exemplar.

I. Historical Context: A Legacy of Stewardship and Resilience

The history of the Menominee Forest is inextricably linked to the history of the Menominee People, often referred to as "the Wild Rice People" (Omaeqnomeneu). Their story is one of profound connection to the land, adaptation, and unwavering commitment to stewardship despite immense external pressures.

A. Ancient Roots: Pre-Colonial Harmony

For over 10,000 years, the Menominee Nation has inhabited their ancestral lands, with the forest serving as the cornerstone of their existence. Unlike European settlers who viewed the forest primarily as a commodity, the Menominee understood it as a living relative, a sacred provider of food, medicine, shelter, and spiritual sustenance. Their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) was built upon generations of observation, experience, and an intimate understanding of the forest’s complex cycles.

This pre-colonial management was not static but involved dynamic, adaptive practices. For instance, controlled burns were sometimes used to clear underbrush, promote specific plant growth, and enhance hunting grounds, mimicking natural fire regimes. Harvesting of timber, wild rice, maple syrup, and medicinal plants was done with deep respect and a keen awareness of sustainability, ensuring that resources were never depleted and always left sufficient for future generations. This philosophy, encapsulated in the "seven generations" principle, mandated that decisions made today must consider their impact on the seventh generation to come.

B. European Contact and the Treaty Era: Shrinking Lands, Enduring Spirit

The arrival of European settlers brought profound changes and immense pressure. Through a series of treaties in the 19th century, the Menominee Nation’s vast ancestral territory, once encompassing millions of acres, was progressively reduced to its current reservation boundaries. This era introduced the foreign concept of private land ownership and the relentless demand for timber to fuel industrial expansion.

Despite the shrinking land base and attempts at forced assimilation, Menominee leaders resisted the wholesale destruction of their forest. They fought to retain their remaining lands, recognizing the forest as not just an economic resource but the very heart of their cultural identity and survival. Their resilience during this period laid the groundwork for future self-determination in forest management.

C. The Reservation Era and Early Commercial Logging: Pioneers of Sustained Yield

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Menominee Reservation was established. External pressures to exploit the forest for immediate profit were intense, often advocating for clear-cutting practices common in the era. However, Menominee leaders, guided by their ancient wisdom, steadfastly opposed these destructive methods. They argued that such practices would decimate the forest, undermine their economy, and betray their cultural heritage.

In a remarkable act of foresight and self-determination, the Menominee Nation established the Menominee Indian Mills in 1908. Under the leadership of figures like Chief Oshkosh and later, sophisticated tribal foresters, they pioneered what would much later be recognized as "sustained yield forestry." While most surrounding forests were being clear-cut, the Menominee began selective logging, harvesting only mature trees and leaving younger, healthier ones to grow. This practice ensured a continuous supply of timber, maintained forest health, and preserved the ecosystem. They developed detailed forest inventories and management plans years, even decades, ahead of most state and federal forestry agencies. This period marked the formal integration of Menominee TEK with emerging Western scientific forestry principles.

D. Termination and Restoration: A Test of Resilience

The mid-20th century presented the greatest challenge to Menominee sovereignty and their sustainable forest management. In 1954, the U.S. Congress passed the Menominee Termination Act, dissolving the tribe’s federal recognition and jurisdiction. The reservation became Menominee County, and tribal assets, including the mill and forest, were transferred to a private corporation, Menominee Enterprises, Inc. (MEI).

Termination proved disastrous. The tribe lost its federal services, leading to widespread poverty, inadequate healthcare, and declining infrastructure. MEI, under pressure to generate profits, was forced to increase logging rates beyond sustainable levels, threatening the very forest that had sustained the Menominee for centuries. The ecological integrity of the forest began to suffer, and the cultural connection was severely strained.

However, the Menominee people rallied. Through decades of tireless activism and political organizing, led by groups like DRUMS (Determination of Rights and Unity for Menominee Shareholders), they fought for the restoration of their tribal status. In 1973, the Menominee Restoration Act was passed, re-establishing the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and reaffirming their sovereignty. This victory was a profound reaffirmation of their commitment to their land and their unique way of life, and it immediately allowed them to re-institute their traditional, sustainable forest management practices.

II. The Philosophy of Menominee Sustainable Forestry

The Menominee approach to forestry is fundamentally different from conventional Western models, which often prioritize maximum timber extraction and short-term economic gains. It is a holistic philosophy rooted in respect, reciprocity, and a deep understanding of interconnectedness.

A. "We Don’t Own the Forest, the Forest Owns Us"

This oft-quoted Menominee saying encapsulates their core philosophy. It rejects the anthropocentric view of nature as a resource to be exploited and instead posits humanity as an integral, subservient part of a larger ecological system. The forest is not a commodity but a living entity, a sacred relative that provides for the people. This perspective fosters an ethic of responsibility and humility, ensuring that management decisions are made with the utmost care and a profound long-term vision.

B. The Seven Generations Principle

Central to Menominee sustainability is the "seven generations" principle. Every decision regarding the forest is weighed against its potential impact on future generations, typically defined as seven generations down the line. This long-term perspective naturally discourages short-sighted, extractive practices and prioritizes the health and resilience of the ecosystem over immediate financial gain. It ensures that the forest will continue to provide for their descendants, just as it has provided for their ancestors.

C. Integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Western Science

The Menominee Forest management system represents a unique and powerful synergy between ancient TEK and modern scientific forestry. TEK provides an invaluable, time-tested understanding of local ecosystems, species interactions, seasonal cycles, and the forest’s spiritual dimensions. This includes knowledge of plant medicinal properties, animal behaviors, soil characteristics, and natural regeneration patterns.

This indigenous knowledge is then augmented and validated by Western scientific tools and methodologies, such as sophisticated mapping (GIS), detailed forest inventories, growth modeling, and ecological monitoring. The Menominee foresters, many of whom are tribal members, are adept at blending these two knowledge systems, creating an adaptive management framework that is both culturally relevant and scientifically robust.

III. Practical Applications of Sustainable Practices

The philosophy of Menominee sustainable forestry translates into a set of highly effective and environmentally sound practical applications.

A. Selective Harvesting and Ecosystem Mimicry

The cornerstone of Menominee forest management is selective harvesting. Unlike clear-cutting, which removes all trees from an area, the Menominee practice involves removing individual trees or small groups of trees. This mimics natural disturbance patterns, such as the fall of an old tree, which creates small openings for sunlight and allows for natural regeneration.

This method maintains a multi-aged, multi-species forest structure, promoting biodiversity and ensuring a continuous forest cover. It minimizes soil disturbance, protects water quality, and preserves the habitat for a wide array of wildlife, from deer and bear to countless bird species. The forest is managed for health and resilience, not just timber volume.

B. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health

Menominee foresters prioritize the overall health and biodiversity of the ecosystem. This means managing for a diverse mix of tree species, including both conifers (like white pine) and hardwoods (like maple, oak, and birch), which are crucial for ecological stability and resilience against pests and diseases. They also protect critical habitats, wetlands, and old-growth characteristics where appropriate, recognizing the intrinsic value of every component of the ecosystem. The result is a thriving, complex forest that supports a rich tapestry of life.

C. Economic Viability and Value-Added Products

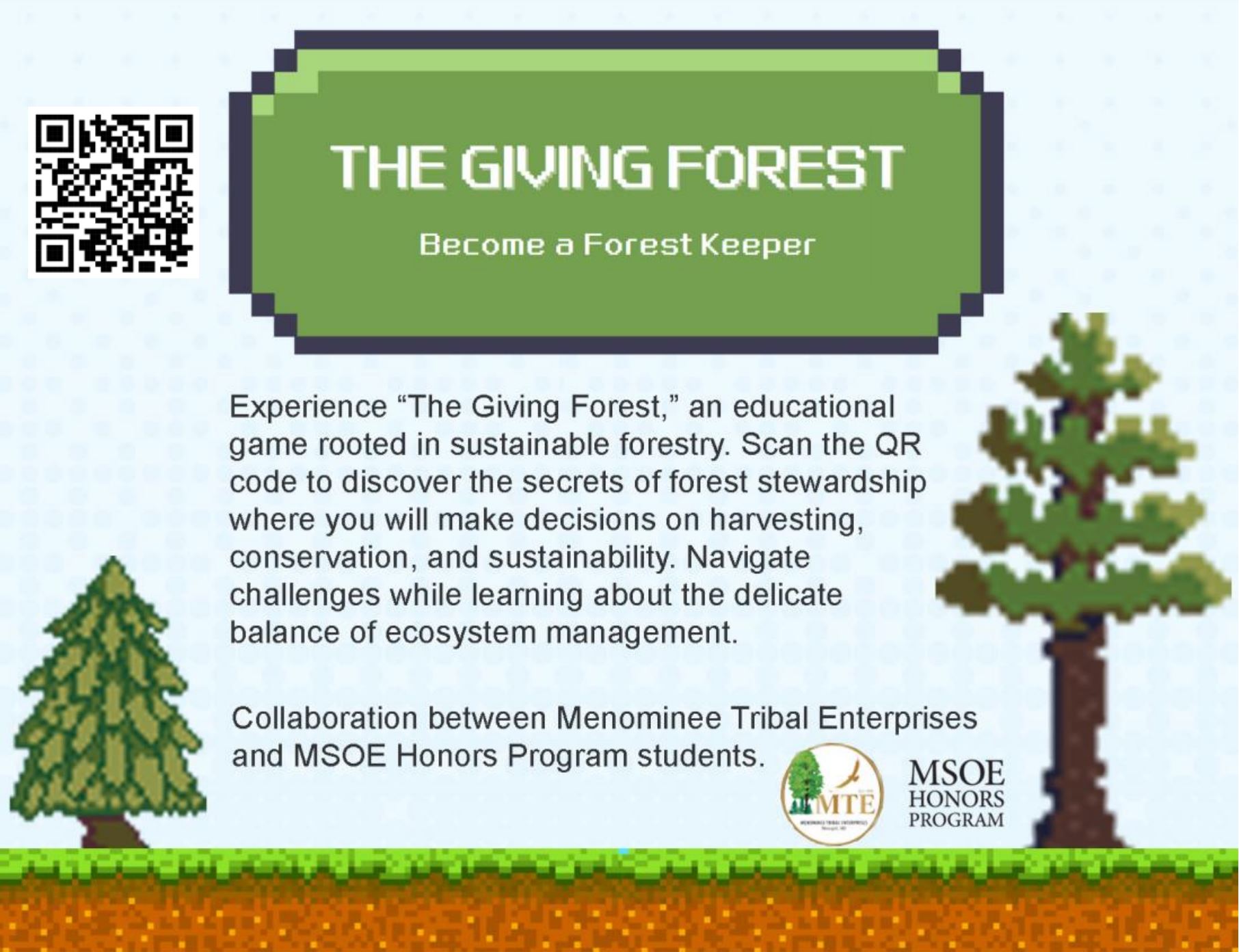

While sustainability is paramount, the Menominee Forest also provides significant economic benefits to the Nation. Through Menominee Tribal Enterprises (MTE), the sustainably harvested timber is processed at their own sawmill, creating value-added products like lumber, flooring, and furniture. This vertical integration not only maximizes economic returns but also creates stable employment opportunities for tribal members within their own community. The forest thus serves as the economic engine for the tribe, funding essential services like education, healthcare, and social programs.

D. Cultural Preservation and Education

The Menominee Forest is also a living classroom and a vital space for cultural preservation. It provides a setting for traditional hunting, gathering of medicinal plants, and spiritual ceremonies. It facilitates the intergenerational transfer of knowledge, as elders teach younger members about the forest’s cycles, its plants and animals, and the Menominee language and traditions intrinsically linked to the land. The forest ensures the continuation of their cultural identity and practices, making it far more than just a timber resource.

IV. Conclusion

The Menominee Forest stands as an extraordinary exemplar of sustainable forest management, demonstrating that it is possible to achieve economic prosperity, ecological integrity, and cultural vitality simultaneously. Its history is a testament to the Menominee Nation’s unwavering commitment to their ancestral lands, their ability to adapt and resist destructive forces, and their profound wisdom in integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern science.

In a world grappling with climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion, the Menominee Forest offers a powerful model for global forest stewardship. It reminds us that true sustainability is not merely about managing resources but about cultivating a respectful, reciprocal relationship with the natural world, ensuring that the gifts of the earth will continue to sustain all generations to come. The Menominee Forest is not just a forest; it is a symbol of resilience, wisdom, and a hopeful path forward for humanity.