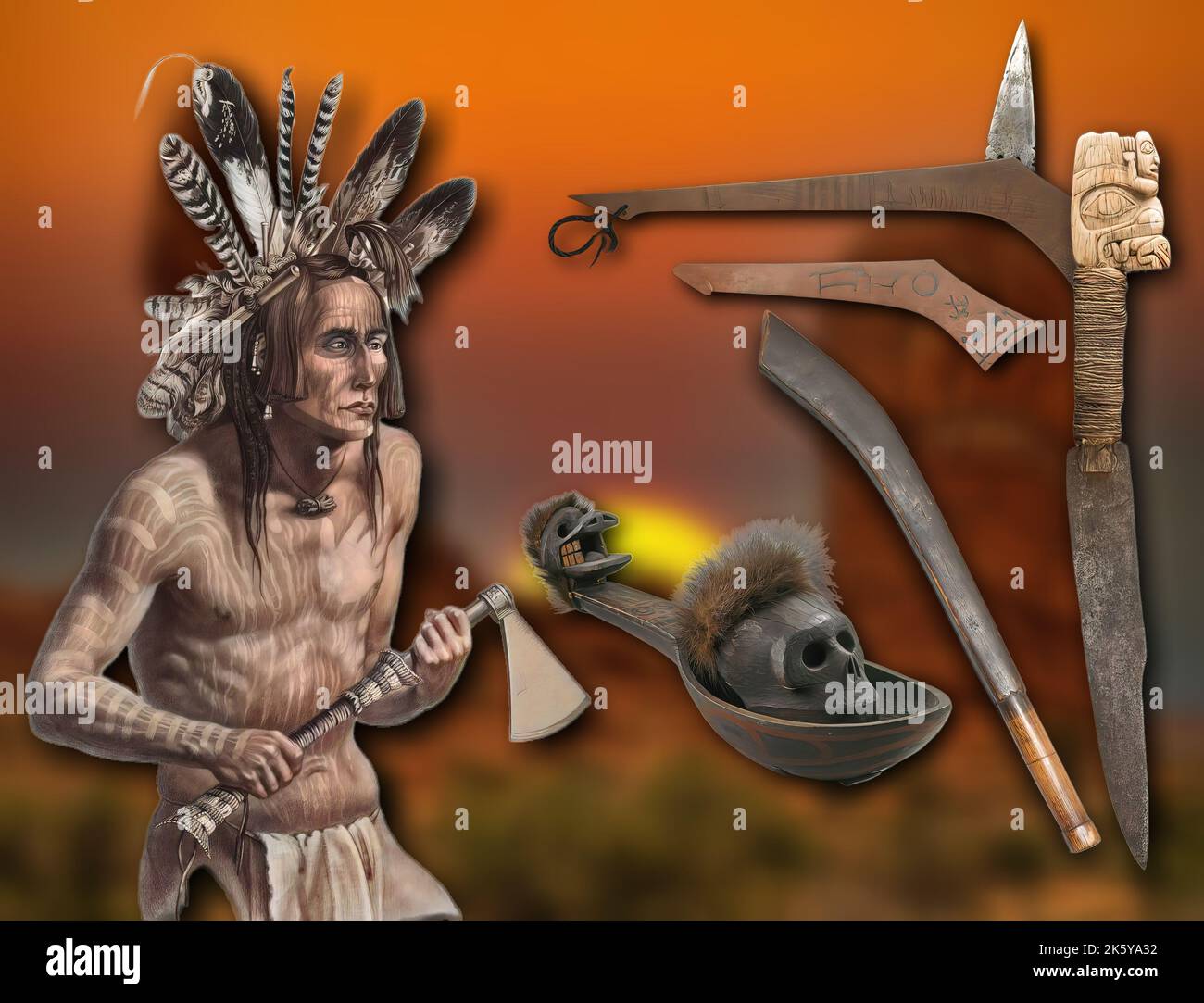

The Forge and the Canvas: Men’s Multifaceted Roles in Native American Art and Hunting Tools

The study of Native American cultures reveals a profound interconnectedness between practical survival, spiritual belief, and artistic expression. Within this intricate tapestry, the roles of men, particularly concerning hunting tools and the art forms intertwined with them, were foundational. Far from being merely utilitarian, these objects were imbued with deep cultural significance, reflecting men’s roles as providers, protectors, innovators, spiritual intermediaries, and storytellers. This essay will delve into the multifaceted contributions of Native American men, examining their ingenuity in crafting essential hunting tools and the sophisticated artistry that transformed these instruments, and related objects, into powerful cultural artifacts.

The Genesis of Ingenuity: Men as Innovators and Toolmakers

At the heart of men’s responsibilities across diverse Native American nations was the role of the hunter and provider. This demanding task necessitated an intimate understanding of the natural world, animal behavior, and, crucially, the development of sophisticated tools. Men were the primary innovators in lithic technology, woodcraft, and bone/antler manipulation, constantly refining designs for efficiency, durability, and specialized function.

Projectile Weapons: The bow and arrow, a ubiquitous hunting technology across North America, exemplifies men’s engineering prowess. The construction of a functional bow required selecting specific types of wood (e.g., Osage orange, hickory, ash, cedar) for flexibility and strength, meticulously shaping it, and often reinforcing it with sinew (animal tendons) for added power and resilience. Arrows were crafted from straight shoots, fletched with feathers (often from specific birds, imbued with symbolic meaning) to ensure stability in flight, and tipped with meticulously flaked stone or bone points. The art of flintknapping, transforming raw chert, obsidian, or quartz into razor-sharp projectile points, scrapers, and knives, was a highly specialized skill, demanding precision, patience, and an intricate understanding of material properties and fracture mechanics.

Prior to the bow and arrow, the atlatl (spear-thrower) was a testament to early engineering ingenuity. This simple lever system significantly increased the velocity and range of a thrown dart or spear, demanding careful balance and construction. Spears themselves, often tipped with larger stone points or hardened wood, were essential for hunting larger game.

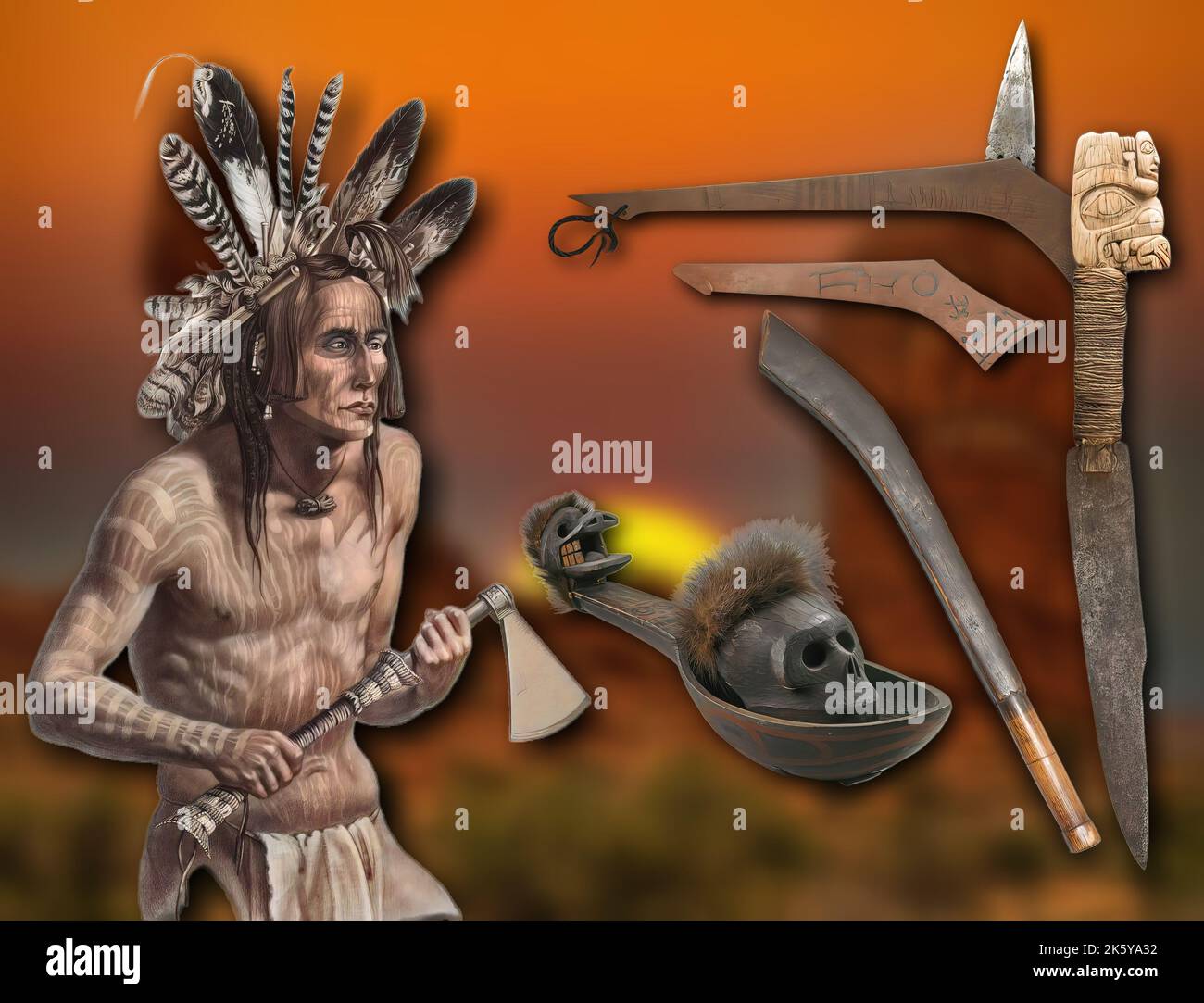

Cutting and Processing Tools: Beyond projectile weapons, men crafted a range of tools vital for processing game and preparing hides. Knives, with their sharp stone blades and handles of wood, bone, or antler, were indispensable for butchering. Scrapers, often made from stone or bone, were used to clean and de-flesh hides, a critical step in their transformation into clothing, shelters, and other necessities.

Trapping and Fishing Gear: While less often highlighted in art discussions, men’s ingenuity extended to passive hunting methods. Traps and snares, ingeniously designed from natural materials like wood and sinew, were set to capture smaller game. In aquatic environments, men crafted harpoons with barbed points (often detachable) for hunting seals, whales, and large fish, as well as complex fishing weirs and nets. The design of canoes and kayaks, particularly among coastal and northern peoples, was a highly developed skill, requiring deep knowledge of hydrodynamics and material properties.

The creation of these tools was not a solitary endeavor but often involved the transmission of knowledge through generations, with fathers and elders teaching younger men the intricate skills and scientific principles embedded in their craft. This educational process reinforced cultural values, ensured continuity of essential technologies, and fostered a deep respect for both the natural world and the human capacity for innovation.

Artistry Beyond Utility: Form, Function, and Meaning

The distinction between "tool" and "art" was often blurred in Native American cultures, particularly in objects crafted by men. While designed for practical function, many hunting tools and related implements were adorned with decorative elements, transforming them into expressions of identity, spiritual belief, and aesthetic appreciation.

Decorating the Instruments of the Hunt:

- Bows and Arrows: Bows might be carved with geometric patterns, animal effigies, or painted with symbolic designs. Arrow shafts could be grooved or painted, sometimes to distinguish ownership or signify a particular hunting society. Quivers, made from hide, were often elaborately decorated with beadwork, quillwork, fringe, and painted motifs depicting animal spirits, successful hunts, or protective symbols.

- Knives and Sheaths: Knife handles, especially those made from bone or antler, were frequently carved with zoomorphic or anthropomorphic figures. The sheaths, typically of rawhide or leather, were canvases for intricate beadwork, porcupine quill embroidery, and painted designs, often reflecting the owner’s clan, accomplishments, or spiritual guardians.

- Atlatls: Early atlatls, while utilitarian, were sometimes adorned with carved animal figures or abstract patterns, suggesting their importance extended beyond mere function.

The rationale behind such embellishment was multifaceted. Decoration could imbue a tool with spiritual power, serving as a prayer for a successful hunt or a protective charm. It could signify the owner’s status, skill, or personal achievements. It also reflected a deep respect for the materials and the animal to be hunted, transforming a practical object into an offering of beauty. The act of creating and decorating these tools was a meditative, spiritual process, connecting the craftsman to the natural world and the unseen forces that governed it.

Ceremonial and Ritual Objects: Men’s artistic contributions extended significantly into the realm of ceremonial and ritual objects, many of which were intrinsically linked to themes of hunting, power, and the natural world.

- Pipes (Calumets): Carved pipes, particularly the "calumets" of the Plains and Woodland peoples, were often made by men and represent a pinnacle of artistic expression. The bowls, typically of pipestone (catlinite), were sculpted into animal effigies, human figures, or abstract forms. The wooden stems were frequently adorned with intricate carvings, beadwork, quillwork, and feathers. These pipes were not merely smoking devices but sacred instruments used in treaties, ceremonies, and personal prayers, mediating communication between humans and the spirit world.

- Masks: In cultures like the Iroquois (False Face Society) and the Pacific Northwest Coast, men were the primary carvers of ceremonial masks. These masks, often representing powerful spirits, mythical creatures, or ancestors, were crucial components of religious ceremonies. They demanded exceptional carving skills, an understanding of form and symbolism, and the ability to imbue the wood with lifelike or terrifying presence.

- Effigies and Fetishes: Smaller carved effigies of animals (e.g., bear, wolf, mountain lion) or human figures, often made from stone or wood, served as fetishes or charms for protection, hunting success, or healing. These objects, while small, showcased remarkable detail and spiritual potency.

- Rock Art (Petroglyphs and Pictographs): Across North America, men were often the creators of petroglyphs (carved into rock) and pictographs (painted on rock). These ancient art forms frequently depict hunting scenes, animal figures, human-like shamans, and abstract symbols, serving as records of hunts, spiritual journeys, and cosmological beliefs.

Regalia and Personal Adornment: The clothing and personal regalia worn by men, particularly for ceremonies, dances, or warfare, also constituted a significant artistic domain. Headdresses, like the feathered war bonnets of the Plains, shields, and painted hide shirts were not merely decorative but conveyed status, achievements, and spiritual protection. Designs often incorporated animal motifs, battle honors, or clan symbols, created through painting, quillwork, beadwork, and the meticulous arrangement of feathers and animal parts. The creation and maintenance of these items, often a lifelong endeavor, were deeply personal and culturally significant artistic practices.

Spiritual and Cultural Interconnectedness

The roles of men in crafting hunting tools and art were deeply embedded in the spiritual and cultural fabric of Native American societies.

- Reciprocity and Respect: The hunter’s relationship with the hunted was one of profound respect and reciprocity. Tools were not just instruments of death but extensions of this spiritual contract. Their embellishment often served as an offering or a prayer to the animal’s spirit, acknowledging its sacrifice and ensuring continued abundance.

- Storytelling and Pedagogy: Art, whether on a tool, a pipe, or a rock face, served as a powerful medium for storytelling and the transmission of knowledge. It depicted historical events, myths, spiritual lessons, and hunting strategies, educating younger generations and reinforcing cultural identity.

- Status and Identity: Mastery in both hunting and craftsmanship conferred significant status within the community. A skilled hunter who also created beautiful and effective tools was highly respected. These objects became markers of personal achievement, bravery, and spiritual connection.

- Community and Collaboration: While men often specialized in certain crafts, the entire community benefited from their skills. The division of labor, where men provided game and tools and women often processed hides and prepared food, was a complementary system that ensured the survival and prosperity of the group.

Conclusion

The roles of Native American men in the creation of hunting tools and art were far more comprehensive than a simple division of labor might suggest. They were engineers, material scientists, skilled artisans, spiritual practitioners, and educators, whose innovations and artistic expressions were fundamental to their survival, cultural identity, and spiritual well-being. The objects they crafted — from the humble arrowhead to the intricately carved ceremonial pipe — were never solely utilitarian. They were imbued with layers of meaning, reflecting a holistic worldview where the practical, the aesthetic, and the sacred were inextricably linked. Understanding these roles offers a profound insight into the richness, complexity, and enduring legacy of Native American cultures, where every object tells a story of ingenuity, reverence, and artistic brilliance.