The Strategic Imperative of Coat Check Policies in Native American Museums: A Multifaceted Approach to Preservation, Pedagogy, and Cultural Reverence

Museum coat check policies, often perceived as mere operational conveniences, represent a critical, multifaceted component of institutional management, particularly within Native American museums. Far from being a peripheral service, these policies are deeply intertwined with the core mission of such institutions: the preservation of invaluable cultural heritage, the facilitation of profound educational experiences, and the fostering of an atmosphere of respect and reverence. This article will meticulously explore the rationale, implementation, and unique significance of coat check policies in Native American museums, elevating their understanding beyond the logistical to the strategic and ethical.

I. Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Museum Services

The evolution of museum services reflects a growing sophistication in institutional practice, moving from simple custodial functions to comprehensive visitor engagement strategies. Early museums, often private collections, offered limited public access and minimal amenities. With the rise of public museums in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the subsequent professionalization of museology, visitor services began to expand. Coat checks emerged as a practical solution to manage the influx of visitors, address security concerns, and enhance the viewing experience. From a theoretical perspective, the coat check aligns with several key tenets of modern museology: conservation science (protecting artifacts), visitor studies (optimizing the visitor journey), and risk management (mitigating potential hazards). For Native American museums, these principles take on an added layer of cultural and ethical significance.

II. Core Rationale for Museum Coat Check Policies

General museum practice dictates coat check policies for several fundamental reasons, each contributing to the institution’s overall efficacy:

A. Artifact Preservation and Environmental Control: Bulky outerwear and oversized bags pose a direct physical threat to artifacts. Accidental brushing, snagging, or dropping can inflict irreparable damage, particularly on fragile materials. Furthermore, external items can introduce dust, pests, and contribute to microclimatic fluctuations within exhibition spaces, challenging stringent environmental controls crucial for long-term preservation.

B. Security and Loss Prevention: Coat checks enhance security on multiple fronts. They reduce the potential for theft of museum property by limiting the places where items could be concealed. Simultaneously, they offer visitors a secure location for their personal belongings, mitigating concerns about carrying valuables through crowded galleries and thereby allowing for more focused engagement with exhibits.

C. Visitor Comfort and Accessibility: Unburdening visitors of heavy coats, backpacks, and cumbersome bags significantly improves their comfort and mobility. This freedom allows for unhindered movement through galleries, closer examination of exhibits, and a more relaxed, extended visit. It also aids in managing visitor flow, preventing bottlenecks in high-traffic areas.

D. Space Management and Aesthetics: In often architecturally constrained or deliberately designed exhibition spaces, the absence of numerous coats and bags hanging or resting on floors maintains the aesthetic integrity of the displays. It maximizes available viewing space and ensures that the curatorial narrative remains unobstructed and visually coherent.

III. The Unique Significance in Native American Museums

While the above rationales apply universally, their importance is amplified within Native American museums due to the specific nature of their collections, their cultural mission, and the profound respect owed to the heritage they steward.

A. Safeguarding Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage:

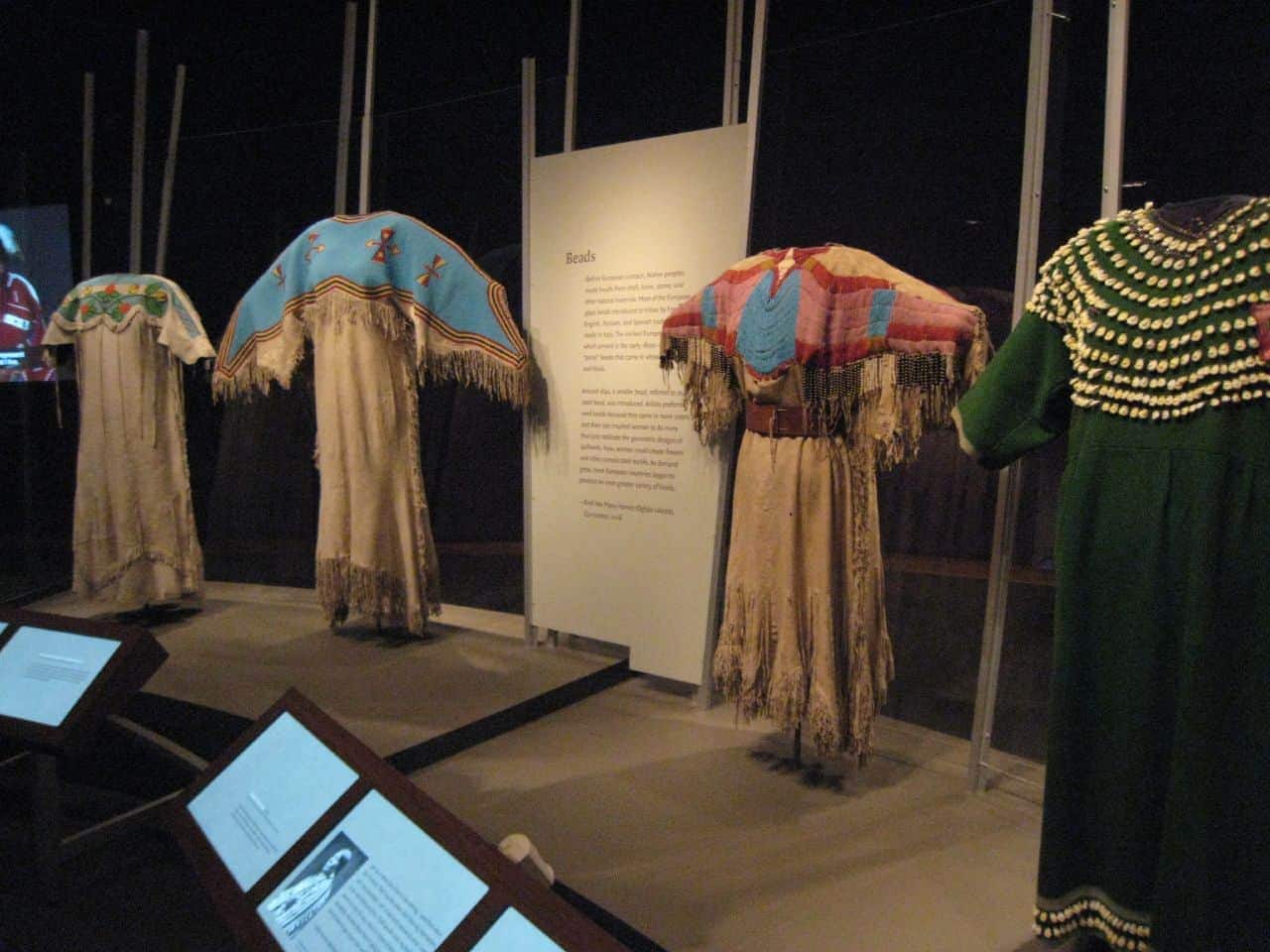

- Material Vulnerability: Native American cultural items are frequently crafted from organic, natural materials such as feathers, hides, quills, plant fibers (basketry, textiles), wood, bone, and pottery. These materials are inherently delicate and highly susceptible to physical abrasion, impact, and environmental degradation. A stray sleeve or an accidentally swung bag could cause irreversible damage to a finely woven basket, dislodge quills from an intricate design, or chip a centuries-old ceramic vessel. The coat check acts as a primary preventative measure against such accidental harm, protecting items that are not merely historical artifacts but living embodiments of cultural knowledge and ancestral artistry.

- Spiritual and Historical Value: The items held in Native American museums are often imbued with deep spiritual, historical, and communal significance. Damage to these objects is not merely a material loss; it represents a disruption to cultural continuity, a diminishment of narrative integrity, and a disrespect to the communities from which they originate. The coat check policy, by proactively safeguarding these items, thus embodies a fundamental ethical commitment to the preservation of Indigenous identity and a reverence for the sacred. It is an act of proactive stewardship that acknowledges the profound weight and meaning these objects carry for their source communities.

B. Fostering Respectful and Immersive Engagement:

- Sacred and Contemplative Spaces: Many Native American museums are designed to evoke a sense of reverence, contemplation, and deep respect for Indigenous cultures. The architectural choices, lighting, and narrative flow often encourage a more introspective and focused visitor experience. The physical encumbrance of heavy coats and bags can disrupt this intended atmosphere, distracting visitors from the profound stories and visual richness of the exhibits. By removing these distractions, the coat check policy facilitates a more immersive and respectful engagement, allowing visitors to connect more deeply with the presented narratives and the spiritual dimensions of the cultural heritage.

- Minimizing Distractions: Beyond physical impediments, bulky items can create sensory distractions. The rustling of coats, the bumping of bags, or the constant adjustment of cumbersome items can pull a visitor’s attention away from the subtle details of an artwork or the quiet intensity of an exhibit. An unburdened visitor is more likely to engage with the educational content, appreciate the aesthetic qualities, and absorb the cultural lessons offered by the museum, thereby fulfilling the institution’s pedagogical mission more effectively.

C. Cultural Sensitivity and Visitor Experience:

- Acknowledging Diverse Needs: Native American museums serve a diverse public, including Indigenous peoples whose connection to the artifacts may be deeply personal and communal. While coat check policies are generally uniform, the underlying philosophy of cultural sensitivity informs their application. The policy, by ensuring the preservation of culturally significant items, indirectly assures Indigenous visitors that their heritage is being treated with the utmost care and respect. This fosters trust and reinforces the museum’s commitment to being a respectful steward of cultural memory.

- Educational Mission: By creating an optimal viewing environment, the coat check policy indirectly supports the museum’s core educational mission. An unobstructed and comfortable visitor is more receptive to learning about the history, resilience, and contemporary vibrancy of Native American cultures. This practical measure thus contributes to the broader goal of fostering cross-cultural understanding and dispelling misconceptions.

IV. Operational Considerations and Best Practices

Effective coat check policies require careful operational planning and consistent execution:

A. Policy Formulation and Communication: Policies must be clearly articulated, easily understandable, and prominently displayed at museum entrances and on institutional websites. The rationale behind the policy, especially concerning artifact preservation, should be communicated to visitors, framing it as a measure of care and respect. Exceptions (e.g., for medical devices, small personal bags for essentials) should be clearly defined.

B. Staff Training: Coat check attendants and front-line staff require comprehensive training not only in logistical procedures (tagging, storage, retrieval) but also in customer service, security protocols, and cultural sensitivity. They should be able to politely and effectively explain the policy’s importance, particularly its role in protecting cultural heritage.

C. Infrastructure and Technology: A well-designed coat check area should be secure, efficiently organized, and equipped with reliable tagging and storage systems. Modern solutions might include automated lockers or digital tracking systems to enhance efficiency and security.

D. Liability and Ethical Frameworks: Museums typically limit their liability for lost or damaged items, a standard practice that must be clearly communicated. However, the ethical imperative to protect both museum property and visitor belongings underpins the entire operation. For Native American museums, this ethical dimension extends to the profound responsibility of safeguarding items of immense cultural and spiritual value.

V. Conclusion

The coat check policy in a Native American museum transcends its utilitarian function to become a strategic pillar supporting the institution’s multifaceted mission. It is a tangible expression of commitment to artifact preservation, an essential component in creating an immersive and respectful visitor experience, and an embodiment of the profound reverence due to Indigenous cultural heritage. By carefully managing visitor belongings, these policies contribute directly to the safeguarding of irreplaceable objects, enabling generations to connect with the rich, living histories of Native American peoples in an environment of dignity, safety, and profound educational engagement. Far from a mere inconvenience, the coat check is an integral, ethically informed practice that underpins the very integrity and purpose of a Native American museum.