The Integrated Repository: A Deep Dive into Native American Museums with Research Libraries

Native American museums, particularly those integrated with robust research libraries, represent a unique and vital nexus for cultural preservation, scholarly inquiry, and community engagement. Far from being mere repositories of artifacts, these institutions serve as dynamic hubs where the tangible heritage of Indigenous peoples is meticulously preserved, interpreted, and made accessible alongside a wealth of textual, oral, and visual documentation. This dual structure offers a holistic approach to understanding Native American cultures, past and present, fostering both public education and advanced academic research.

The Museum Component: A Window into Indigenous Cultures

The museum component of such an institution is dedicated to the acquisition, preservation, exhibition, and interpretation of material culture created by Native American peoples across the continent. Its primary aim is to tell the diverse stories of Indigenous nations, celebrating their resilience, creativity, and enduring cultural practices.

1. Collections and Exhibitions:

The collections typically span vast periods, from pre-contact archaeological finds to contemporary art and cultural expressions. They encompass a wide array of objects, including:

- Archaeological Artifacts: Tools, pottery, textiles, and ceremonial objects that illuminate ancient lifeways and technological advancements.

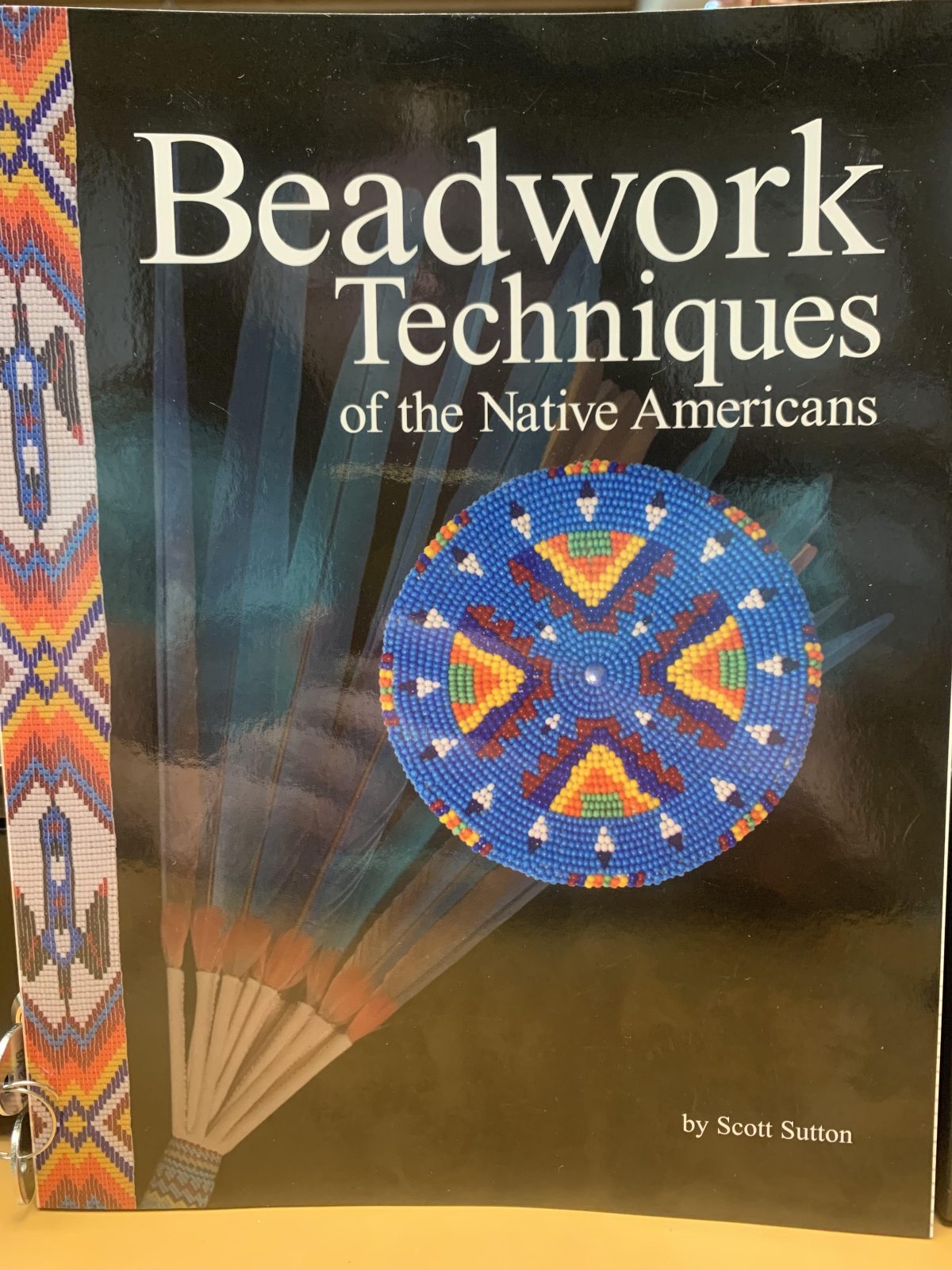

- Ethnographic Collections: Items collected from living cultures, such as regalia, basketry, traditional clothing, musical instruments, and domestic tools, which provide insights into social structures, spiritual beliefs, and daily life.

- Fine Art: A growing focus on contemporary Native American art, showcasing painting, sculpture, photography, and mixed media that address modern Indigenous identities, political issues, and artistic innovation.

- Historical Documents and Photographs: While often overlapping with library holdings, some documents and photographs are curated specifically for their visual storytelling potential within exhibitions.

Exhibitions are meticulously designed to move beyond static displays. Modern Native American museums prioritize narratives that are co-created with or directly presented by Indigenous voices. This often involves:

- Decolonizing Methodologies: Critically examining past collecting practices and challenging Eurocentric interpretations. This leads to exhibitions that emphasize Indigenous epistemologies and perspectives.

- Living Cultures: Highlighting the continuity and dynamism of Native American cultures, rather than presenting them as relics of the past. This includes contemporary issues, language revitalization efforts, and modern ceremonial practices.

- Thematic and Regional Focus: Exhibitions may explore specific themes (e.g., sovereignty, environmental stewardship, artistic movements) or focus on the cultural distinctiveness of particular tribal nations or geographic regions.

2. Educational and Public Programs:

Beyond exhibitions, the museum component is a vibrant center for public education. Programs are designed for diverse audiences, from schoolchildren to adult learners, and often include:

- Workshops: Hands-on activities demonstrating traditional arts, crafts, and skills (e.g., basket weaving, beadwork, storytelling).

- Lectures and Symposia: Featuring Indigenous scholars, elders, artists, and community leaders discussing a range of topics pertinent to Native American history, culture, and contemporary life.

- Performances: Showcasing traditional dances, music, and oral traditions, often performed by tribal members.

- Community Outreach: Collaborating directly with tribal communities to develop programs that meet their specific needs, such as language immersion classes or cultural heritage workshops for youth.

3. Ethical Stewardship and Repatriation:

A crucial aspect of Native American museums is their commitment to ethical stewardship, particularly concerning the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the United States. This involves:

- Provenance Research: Thoroughly investigating the origin and collection history of all items, especially human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.

- Consultation with Tribes: Proactively engaging with descendant communities to identify culturally sensitive materials and facilitate their return or respectful management.

- Respectful Display: Ensuring that objects, particularly sacred ones, are displayed with appropriate cultural sensitivity and only with tribal permission, if at all.

The Research Library Component: The Engine of Knowledge and Inquiry

The research library within a Native American museum is not merely an auxiliary service; it is an indispensable partner that provides the contextual depth and scholarly resources necessary for a comprehensive understanding of Indigenous cultures. It serves as a specialized archive and repository of knowledge, supporting both internal museum functions and external academic and community research.

1. Holdings and Collections:

The library’s collections are highly specialized and often unique, comprising a rich array of primary and secondary sources:

- Archival Collections: This is often the crown jewel, including tribal records, personal papers of Indigenous leaders and activists, missionary records, government documents pertaining to Native American policy, land treaties, and legal documents. These primary sources offer direct insights into historical events and Indigenous perspectives.

- Oral Histories: Recorded interviews with elders, community members, and knowledge keepers, preserving invaluable linguistic, cultural, and historical information that may not exist in written form. These collections are often subject to strict access protocols to respect cultural protocols and individual privacy.

- Rare Books and Manuscripts: Early ethnographic accounts, travel narratives, linguistic studies, and historical texts, providing critical (though sometimes biased) perspectives from past eras.

- Photographic and Audiovisual Archives: Extensive collections of historical and contemporary photographs, films, and sound recordings documenting Indigenous peoples, landscapes, ceremonies, and daily life.

- Published Materials: A comprehensive collection of secondary sources, including scholarly monographs, journals, dissertations, and exhibition catalogs on Native American history, anthropology, art, literature, law, and politics.

- Tribal Publications: Newspapers, newsletters, and literary works produced by Native American communities, offering Indigenous perspectives on current events and cultural life.

- Linguistic Resources: Dictionaries, grammars, and language learning materials for various Native American languages, supporting revitalization efforts.

2. Users and Access:

The research library serves a diverse constituency:

- Museum Staff: Curators, educators, and exhibition designers rely heavily on library resources to research collections, develop exhibition narratives, and create educational programs.

- Academics and Scholars: Researchers from various disciplines (history, anthropology, sociology, Indigenous studies, law) utilize the library for in-depth scholarly inquiry, leading to books, articles, and dissertations.

- Tribal Members and Genealogists: Individuals tracing their ancestry, researching tribal history, or seeking cultural knowledge for personal or community purposes find the library invaluable.

- Students: Undergraduate and graduate students conducting research for papers and projects.

- The General Public: Engaged citizens seeking deeper understanding beyond the museum’s public exhibitions.

Access to certain collections, particularly sensitive cultural materials or oral histories, is carefully managed through ethical protocols developed in consultation with descendant communities, ensuring respect for cultural intellectual property rights and privacy.

3. Preservation and Digitization:

The library is also responsible for the long-term preservation of its fragile and unique materials. This involves:

- Conservation: Specialized techniques to stabilize and repair deteriorating documents, photographs, and audiovisual recordings.

- Environmental Controls: Maintaining optimal temperature and humidity to prevent degradation.

- Digitization: A critical ongoing effort to make collections more accessible globally while simultaneously creating preservation copies. This often involves complex metadata creation and secure digital archiving.

The Synergy: Bridging Display and Discovery

The true power of a Native American museum with an integrated research library lies in its synergy. The two components are mutually reinforcing, creating an institution that offers a holistic and dynamic understanding of Indigenous cultures.

1. Informing Exhibitions: Library research directly informs and enriches museum exhibitions. Curators delve into archival documents, oral histories, and scholarly texts to provide historical context, identify accurate narratives, and ensure culturally appropriate interpretations of artifacts. Conversely, the physical presence of artifacts in the museum can inspire new lines of inquiry within the library.

2. Holistic Understanding: This integrated approach allows visitors and researchers to move seamlessly between material culture and documentary evidence. An object on display in the museum can be illuminated by a corresponding photograph, a written account, or an oral history transcript found in the library, offering a richer, multi-sensory understanding. This bridges the gap between the "what" (the object) and the "why" and "how" (its context and meaning).

3. Empowering Indigenous Voices: The library’s emphasis on primary sources, especially tribal records and oral histories, is crucial for decolonizing narratives. It allows Indigenous peoples to tell their own stories, in their own words, providing counter-narratives to historical biases. The museum then presents these narratives, often directly from tribal perspectives, informed by the library’s deep resources.

4. Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research: The combined resources attract a wider range of scholars, fostering interdisciplinary research that connects anthropology, history, art history, linguistics, law, and Indigenous studies in new and innovative ways.

5. Community Collaboration and Cultural Revitalization: The integrated institution becomes a vital resource for Native American communities themselves. They can access their own histories, traditions, and linguistic resources for cultural revitalization projects, language instruction, and educational initiatives within their nations. The museum and library often work together to support these community-led efforts.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their immense value, these institutions face ongoing challenges:

- Funding: Securing adequate funding for preservation, digitization, staffing, and new acquisitions is a constant struggle.

- Digital Transformation: The need to digitize vast collections while ensuring ethical access, data sovereignty, and robust digital infrastructure is a complex and expensive undertaking.

- Repatriation and Ethical Stewardship: Continuing to navigate the complexities of NAGPRA and evolving ethical standards in collaboration with descendant communities remains a priority for both museum and library components.

- Staffing: Attracting and retaining diverse, culturally competent staff, including Indigenous professionals, is essential for authentic representation and effective service.

- Evolving Narratives: Continuously adapting to new scholarship, contemporary Indigenous voices, and changing public understanding of Native American histories and cultures.

In conclusion, Native American museums with integrated research libraries are more than just cultural institutions; they are dynamic centers of knowledge production, cultural affirmation, and societal dialogue. By meticulously preserving both tangible heritage and invaluable documentation, and by actively fostering Indigenous voices and scholarly inquiry, they play an indispensable role in ensuring that the rich and complex histories, cultures, and contemporary realities of Native American peoples are understood, respected, and celebrated for generations to come. They stand as enduring testaments to resilience, creativity, and the power of integrated knowledge.