The Enduring Legacy: A Deep Dive into Shoshone Tribal History and Land (An Encyclopedic Exhibit Overview)

Introduction: Guardians of a Vast Inland Sea

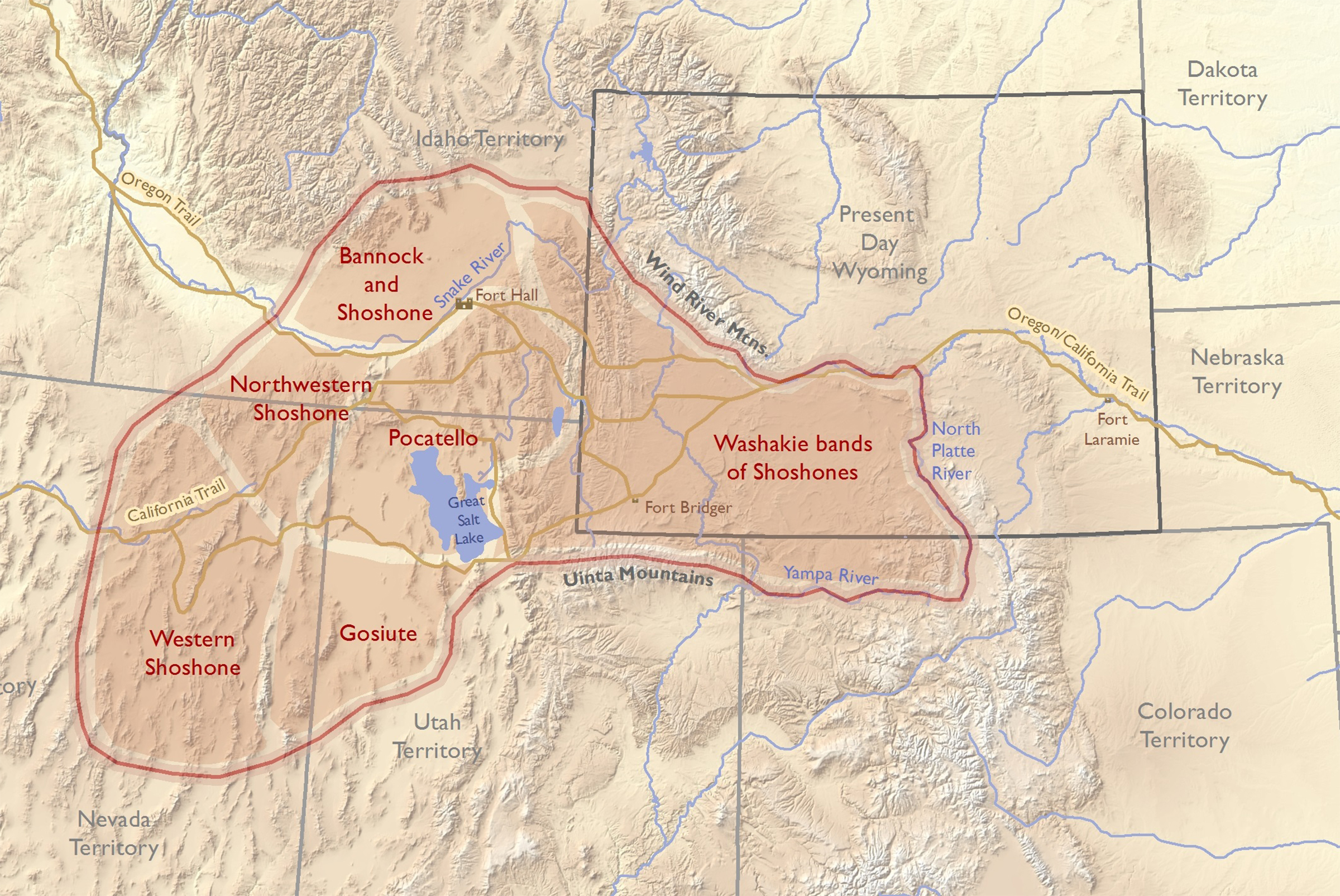

The Shoshone people, known by various self-designations such as Newe (The People), represent a profound and enduring presence across a vast and diverse landscape of North America. Their historical territories spanned from the arid Great Basin, across the verdant Snake River Plain, into the towering Rocky Mountains, and even onto the Great Plains. This immense geographical spread fostered a remarkable adaptability and cultural diversity among Shoshone bands, who, despite their differences, shared a common linguistic heritage (Numic, a branch of the Uto-Aztecan family) and a deep, spiritual connection to their ancestral lands. An exhibit dedicated to Shoshone tribal history and land would serve not merely as a historical recounting, but as a vibrant testament to resilience, innovation, and an unwavering commitment to cultural preservation in the face of profound change.

Section 1: Pre-Contact Era – A Tapestry of Adaptation and Abundance

Visitors to this exhibit would begin their journey in the pre-contact era, a period stretching back thousands of years before European arrival. Interpretive panels would highlight archaeological evidence, including projectile points, grinding stones, and remnants of ancient dwellings, illustrating the long-standing Shoshone occupation of the land.

- Geographic Diversity and Subsistence Strategies: The exhibit would emphasize the varied environments inhabited by the Shoshone and the sophisticated subsistence methods developed in response.

- Great Basin Shoshone (Western Shoshone, Goshute, Panamint): This section would depict a highly mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle, adapted to the sparse resources of the desert. Dioramas might show families gathering pine nuts, digging for roots (like camas), snaring rabbits and other small game, and utilizing sophisticated basketry for collection and storage. The seasonal round, a meticulous calendar of resource availability, would be a key theme.

- Northern Shoshone (Idaho, Wyoming, Utah): Here, the focus shifts to the Snake River Plain and its tributaries. Displays would feature tools for fishing, particularly salmon, which was a crucial protein source. The gathering of camas bulbs, a staple food, would be illustrated, alongside the hunting of deer, elk, and antelope.

- Eastern Shoshone (Wind River, Wyoming): This group, more influenced by Plains cultures, would be shown after the introduction of the horse. Prior to horses, they were pedestrian hunters of deer and elk, but with the horse, they became formidable bison hunters. Artifacts like stone tools, bone awls, and early pottery would demonstrate their ingenuity.

- Social Organization and Worldview: This section would explore the band-level social structure, often based on kinship, and the egalitarian nature of leadership. A central theme would be the Shoshone worldview, emphasizing a reciprocal relationship with the land and its resources, guided by spiritual beliefs and oral traditions. Multimedia kiosks would present animated maps showcasing seasonal migration patterns and the interconnectedness of their resource territories.

Section 2: The Era of Transformation – Encounter, Conflict, and Contraction

This pivotal section would chronicle the dramatic changes brought about by European contact, beginning in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- The Arrival of Horses and Trade: The exhibit would detail the transformative impact of the horse, introduced through trade networks from the Spanish. For the Eastern Shoshone, the horse revolutionized hunting, warfare, and mobility, enabling them to compete with Plains tribes. For other Shoshone groups, horses facilitated trade and movement but did not entirely alter their traditional subsistence patterns. Artifacts would include early horse tack, beaded items, and trade goods.

- Explorers, Trappers, and Settlers: The encroachment of Euro-American explorers (e.g., Lewis and Clark, with Sacagawea, a Lemhi Shoshone woman, as their guide), fur trappers, and eventually Mormon and other settlers, would be presented chronologically. Maps would illustrate the expanding footprint of non-Native populations and the shrinking of Shoshone territories.

- Disease and Demographic Collapse: A somber but crucial part of the exhibit would address the devastating impact of introduced diseases like smallpox and cholera, which decimated Shoshone populations, often preceding direct contact with settlers. Interpretive panels would convey the scale of this demographic catastrophe.

- Treaties and Land Cessions: The mid-19th century saw a series of treaties, often coerced and poorly understood by the Shoshone, which drastically reduced their land holdings. Key treaties like the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1863 and 1868 (establishing the Wind River Reservation) and the Box Elder Treaty of 1863 (affecting Northern Shoshone and Bannock) would be examined. Displays would include reproductions of treaty documents and maps showing the dramatic loss of ancestral lands.

- Conflict and Resistance: This section would highlight periods of violent conflict, driven by land encroachment, resource competition, and cultural misunderstandings.

- The Bear River Massacre (1863): A solemn display would recount this tragic event, where U.S. troops attacked a Northern Shoshone encampment, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of men, women, and children. First-hand accounts and historical photographs (if available) would lend gravity to this dark chapter.

- The Snake War (1864-1868): This prolonged conflict between the U.S. Army and various Shoshone and Paiute bands across the Great Basin and Snake River Plain would be explored, illustrating the desperate fight to retain traditional ways of life.

- Reservation Life and Assimilation Policies: The establishment of reservations (e.g., Wind River, Fort Hall, Duck Valley, Goshute) marked a new era. The exhibit would explore the challenges of adapting to sedentary life, the imposition of U.S. federal policies aimed at assimilation (e.g., the Dawes Act, boarding schools), and the suppression of traditional languages and ceremonies. Personal testimonies and historical photographs from boarding schools would convey the profound impact on individuals and families.

Section 3: Resilience, Revitalization, and Self-Determination (20th Century to Present)

The final section would celebrate the Shoshone people’s enduring resilience, their fight for self-determination, and the ongoing revitalization of their cultures.

- The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) and Tribal Governance: The exhibit would explain how the IRA of 1934 allowed tribes to re-establish their own governments and constitutions, laying the groundwork for modern tribal sovereignty. Displays would feature images of early tribal councils and contemporary governmental structures.

- Cultural Preservation and Language Revitalization: This vital component would showcase efforts to reclaim and strengthen Shoshone identity.

- Language Programs: Interactive kiosks would offer opportunities to learn basic Shoshone phrases and hear the spoken language, emphasizing its importance as a carrier of culture and worldview.

- Traditional Arts and Crafts: Displays of contemporary Shoshone beadwork, basketry, quillwork, regalia, and storytelling would demonstrate the continuity of artistic traditions and their evolution. Videos of traditional dances and ceremonies would offer a glimpse into vibrant cultural practices.

- Economic Development and Land Management: The exhibit would highlight modern tribal enterprises, including casinos, natural resource management (e.g., timber, oil, gas), and tourism, demonstrating efforts to build sustainable economies and exercise self-sufficiency. The role of tribal governments in managing their lands and resources, often in collaboration with federal agencies, would be emphasized.

- Land and Water Rights Struggles: The ongoing battles for the recognition and protection of treaty rights, land claims, and water rights would be addressed. Case studies of successful legal actions or ongoing negotiations would illustrate the continued importance of land and resources for Shoshone sovereignty and well-being. Maps would contrast historical treaty lands with current reservation boundaries, underscoring the enduring significance of ancestral territories.

- Environmental Stewardship: The Shoshone deep-seated connection to the land translates into modern environmental stewardship. This section would feature examples of tribal conservation efforts, traditional ecological knowledge applied to contemporary challenges, and the Shoshone voice in regional and national environmental discussions.

- Contemporary Voices: The exhibit would culminate with a strong emphasis on contemporary Shoshone voices. Interviews with elders, youth, artists, and leaders would provide personal narratives of identity, challenges, and aspirations, reinforcing the idea that Shoshone history is not static but a living, evolving narrative.

Conclusion: A Living Heritage

An exhibit on Shoshone tribal history and land would transcend a mere chronological account. It would be an immersive experience, inviting visitors to understand the profound connection between the Shoshone people and their diverse ancestral homelands. From the ingenuity of pre-contact subsistence to the trauma of colonial expansion and the triumph of modern cultural revitalization, the story of the Shoshone is a powerful narrative of adaptation, perseverance, and the enduring strength of a people who remain, as they have always been, the rightful stewards of their land and their vibrant heritage. It is a story not just of the past, but of a dynamic and influential present and future.