Virtual Tours of Native American Cultural Exhibits: A Deep Dive into Digital Preservation and Representation

The advent of advanced digital technologies has ushered in a transformative era for cultural heritage institutions, profoundly reshaping how the public interacts with and understands history. Among these innovations, the virtual tour stands out as a powerful pedagogical and archival tool, offering unprecedented access to collections previously constrained by geography, time, and physical limitations. This article delves into the intricate landscape of virtual tours specifically applied to Native American cultural exhibits, exploring their technological modalities, pedagogical benefits, inherent ethical complexities, and future potential in fostering a more nuanced, respectful, and accessible understanding of Indigenous cultures.

The Imperative for Digital Access and Cultural Stewardship

Traditional museum spaces, while invaluable, often present inherent barriers. Geographic distance, mobility challenges, and the sheer volume of artifacts that remain in storage limit public engagement. For Native American cultural heritage, these barriers are compounded by historical contexts of dispossession, forced assimilation, and the often-problematic representation within colonial institutional frameworks. Virtual tours emerge as a crucial response to these challenges, offering:

- Global Accessibility: Bridging geographical divides, enabling individuals worldwide, including Indigenous diaspora communities, to connect with cultural objects and narratives.

- Enhanced Preservation: Creating high-fidelity digital surrogates of fragile artifacts, reducing the need for direct handling and exposure, thus safeguarding them for future generations.

- Educational Outreach: Providing dynamic, interactive learning resources for K-12 students, university scholars, and lifelong learners, irrespective of their proximity to physical institutions.

- Amplifying Indigenous Voices: Offering platforms for self-representation, allowing Native communities to control their narratives, interpret their heritage, and share their knowledge on their own terms.

Technological Modalities and Their Capabilities

Virtual tours leverage a diverse array of digital technologies, each offering distinct capabilities for immersion, interactivity, and detailed representation:

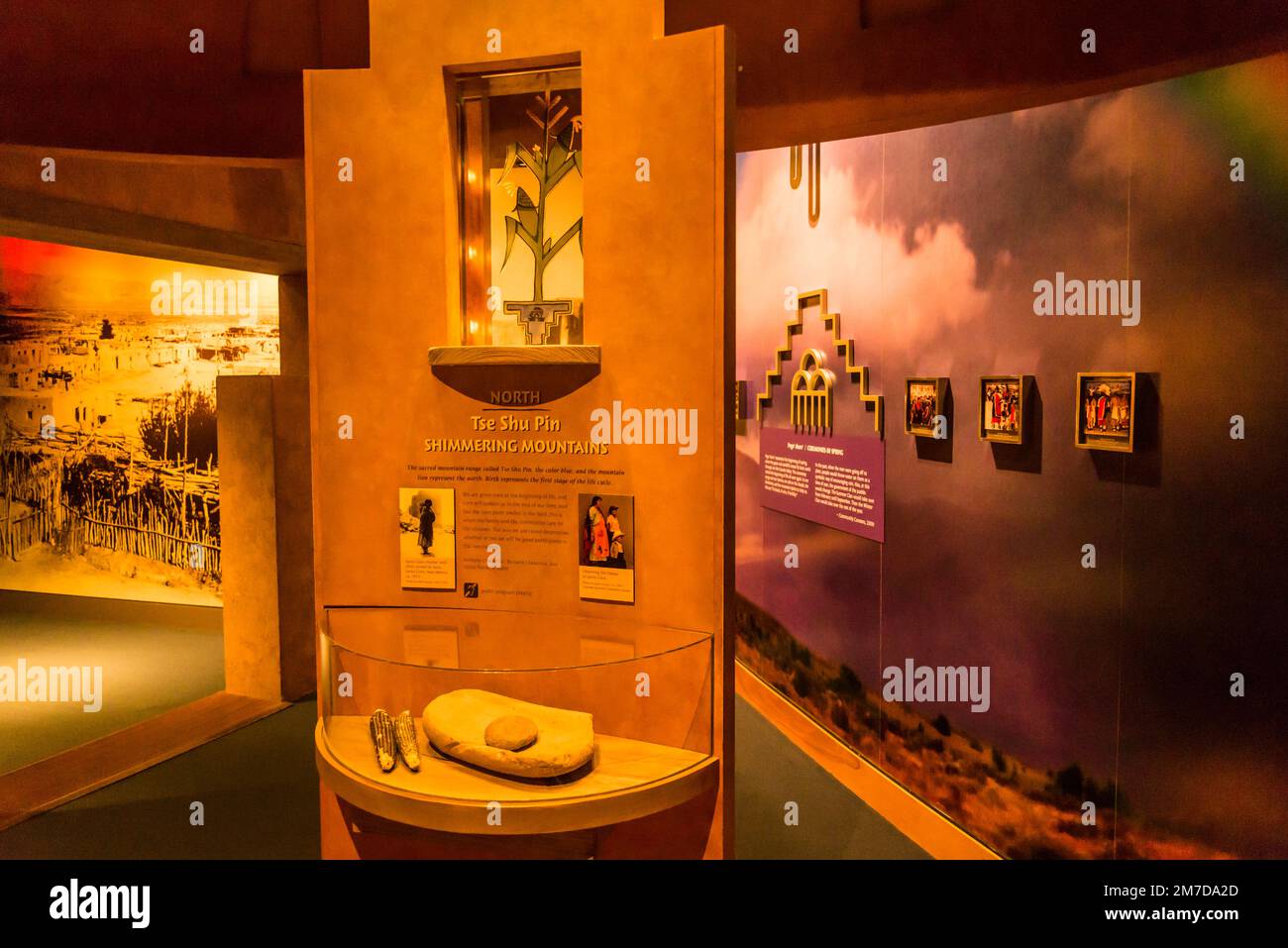

1. 360-Degree Panoramas and Interactive Maps

At the foundational level, many virtual tours utilize 360-degree photographic panoramas stitched together to create immersive room views. These often integrate interactive hotspots that, when clicked, reveal textual descriptions, audio commentary, or close-up images of specific artifacts. While less immersive than advanced VR, this modality is highly accessible, requiring only a standard web browser, and provides an intuitive "walk-through" experience of an exhibit space. Institutions like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) have successfully deployed such tours to navigate their extensive collections and architectural spaces.

2. 3D Digitization and Photogrammetry

For individual artifacts, 3D digitization techniques, particularly photogrammetry, are transformative. Hundreds of photographs taken from multiple angles are processed by software to create highly accurate, detailed 3D models. These models can be rotated, zoomed, and examined from any perspective, offering a level of scrutiny impossible in a physical display case. This allows users to appreciate the intricate craftsmanship, material textures, and functional aspects of objects like pottery, weaving, tools, or ceremonial regalia. Some platforms even enable "disassembly" of complex objects into their constituent parts, revealing hidden details or construction methods.

3. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR)

The pinnacle of immersive virtual tours lies in VR and AR.

- Virtual Reality (VR): Using headsets, VR transports users into fully rendered digital environments. For Native American exhibits, this means not just viewing an object, but potentially "entering" a recreated historical village, participating in a virtual ceremony (with appropriate cultural permissions), or standing on ancestral lands. VR can provide a profound sense of presence and experiential learning, allowing users to understand the spatial relationships between objects, people, and their environment.

- Augmented Reality (AR): AR overlays digital information onto the real world via smartphone or tablet screens. In an exhibit context, an AR app could allow a user to point their device at a physical artifact and instantly access a wealth of supplementary information – historical context, related oral histories, tribal language pronunciations, or even animated reconstructions of the object’s use. This enhances the physical visit with a rich digital layer.

4. Digital Storytelling and Multimedia Integration

Beyond mere visual representation, effective virtual tours of Native American cultural exhibits integrate robust multimedia elements. This includes:

- Audio Narratives: Featuring the voices of tribal elders, historians, and artists, providing authentic interpretations and oral histories that are central to many Indigenous cultures.

- Video Documentaries: Offering deeper contextualization through interviews, archival footage, and contemporary performances.

- Interactive Timelines and Maps: Placing artifacts within broader historical and geographical frameworks, illustrating migration patterns, land cessions, and cultural diffusion.

- Language Revitalization Components: Incorporating Indigenous languages through audio pronunciations, vocabulary lessons, and cultural phrases, supporting ongoing efforts to preserve and revitalize these vital aspects of heritage.

Enhancing Engagement and Understanding

The strategic deployment of these technologies can profoundly enhance the visitor’s engagement and understanding of Native American cultures:

- Deep Contextualization: Virtual platforms allow for the presentation of layers of information that are impractical in physical spaces. Beyond a simple label, an artifact can be linked to its creation story, its use in ceremony, its specific tribal origin, the land from which its materials were sourced, and its contemporary significance. This move from mere object display to rich narrative is vital for understanding Indigenous worldviews.

- Counteracting Stereotypes: By giving direct voice to Indigenous peoples and presenting diverse, nuanced narratives, virtual tours can actively dismantle long-standing stereotypes and oversimplifications often perpetuated by colonial historical accounts. They can showcase the incredible diversity among hundreds of distinct Native nations, each with unique languages, traditions, and artistic expressions.

- Promoting Empathy and Perspective-Taking: Immersive VR experiences, for example, can transport users into historical scenarios or contemporary Indigenous communities, fostering a deeper sense of empathy and challenging preconceived notions. Understanding the impact of historical events like forced relocation or resource extraction becomes more visceral when experienced through a simulated environment or through first-person digital narratives.

- Facilitating Research and Scholarship: Digital surrogates of artifacts, coupled with extensive metadata, create invaluable resources for researchers globally. Scholars can access high-resolution images, 3D models, and associated archival materials without needing to travel, accelerating academic inquiry and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Ethical Considerations and Challenges

Despite their immense potential, virtual tours of Native American cultural exhibits are fraught with significant ethical considerations that demand careful navigation:

1. Ownership, Control, and Data Sovereignty

A primary concern is the ownership and control over digital representations of cultural heritage. Who owns the 3D model of a sacred object? Who has the right to decide how it is displayed, interpreted, or monetized? The principle of data sovereignty dictates that Indigenous communities should retain control over their cultural data, including its digitization, access, and use. This necessitates genuine partnerships, memoranda of understanding, and clear protocols established with tribal nations from the outset of any digitization project.

2. Representation and Authenticity

The digital realm, like the physical museum, can inadvertently perpetuate misrepresentation or cultural appropriation if not handled with extreme sensitivity. Ensuring authenticity requires:

- Tribal Consultation: Engaging directly with source communities at every stage – from selection of objects for digitization, to the development of narratives, to the final presentation.

- Avoiding "Digital Colonialism": Ensuring that the virtual space doesn’t merely replicate the power dynamics of physical museums, where non-Indigenous institutions often dictate the terms of display.

- Respecting Sacredness: Not all cultural objects are appropriate for public display, whether physical or virtual. Sacred items, ceremonial knowledge, or sensitive historical narratives may be subject to specific cultural protocols regarding access and dissemination, which must be rigorously respected.

3. The Digital Divide and Accessibility

While virtual tours aim to enhance accessibility, the "digital divide" remains a challenge. Communities lacking reliable internet access, necessary hardware (e.g., VR headsets), or digital literacy skills can be excluded from these benefits. Equitable access strategies, such as mobile exhibit units or community-based viewing stations, are essential to truly democratize access.

4. Loss of Tangibility and Aura

The unique "aura" of an original artifact – its physical presence, the subtle scent of aged materials, the sense of history embedded in its very being – cannot be fully replicated digitally. While virtual tours offer unparalleled access to visual information, they cannot entirely substitute the deeply sensory and spiritual experience of encountering a physical object, particularly one imbued with cultural significance. This necessitates a balanced approach, where virtual tours complement, rather than completely replace, physical engagement.

Future Directions and Collaborative Models

The future of virtual tours for Native American cultural exhibits lies in increasingly sophisticated, collaborative, and ethically informed approaches:

- Enhanced Immersion: Integration of haptic feedback for simulated tactile experiences, advanced AI for personalized learning pathways, and more sophisticated interactive storytelling.

- Indigenous-Led Development: A shift towards projects entirely conceived, designed, and executed by Indigenous communities and cultural institutions, ensuring genuine self-representation and adherence to cultural protocols. Initiatives like the Reciprocal Research Network (RRNet) demonstrate the power of collaborative digital platforms.

- Hybrid Models: Integrating virtual tours with physical exhibitions and community events, creating a symbiotic relationship where digital resources enhance and extend the physical experience.

- Focus on Living Cultures: Moving beyond static historical displays to incorporate contemporary Native art, language, activism, and community life, demonstrating the dynamism and resilience of Indigenous cultures.

Conclusion

Virtual tours of Native American cultural exhibits represent a powerful frontier in cultural preservation, education, and reconciliation. When developed with careful consideration of technological capabilities, pedagogical impact, and, most critically, rigorous ethical frameworks centered on Indigenous sovereignty and authentic representation, these digital platforms can profoundly transform public understanding. They offer a pathway to dismantle historical injustices, amplify diverse voices, and foster a deeper, more respectful appreciation for the rich and enduring heritage of Native American peoples, ensuring that their stories are told, their objects are seen, and their cultures thrive in an increasingly digital world.